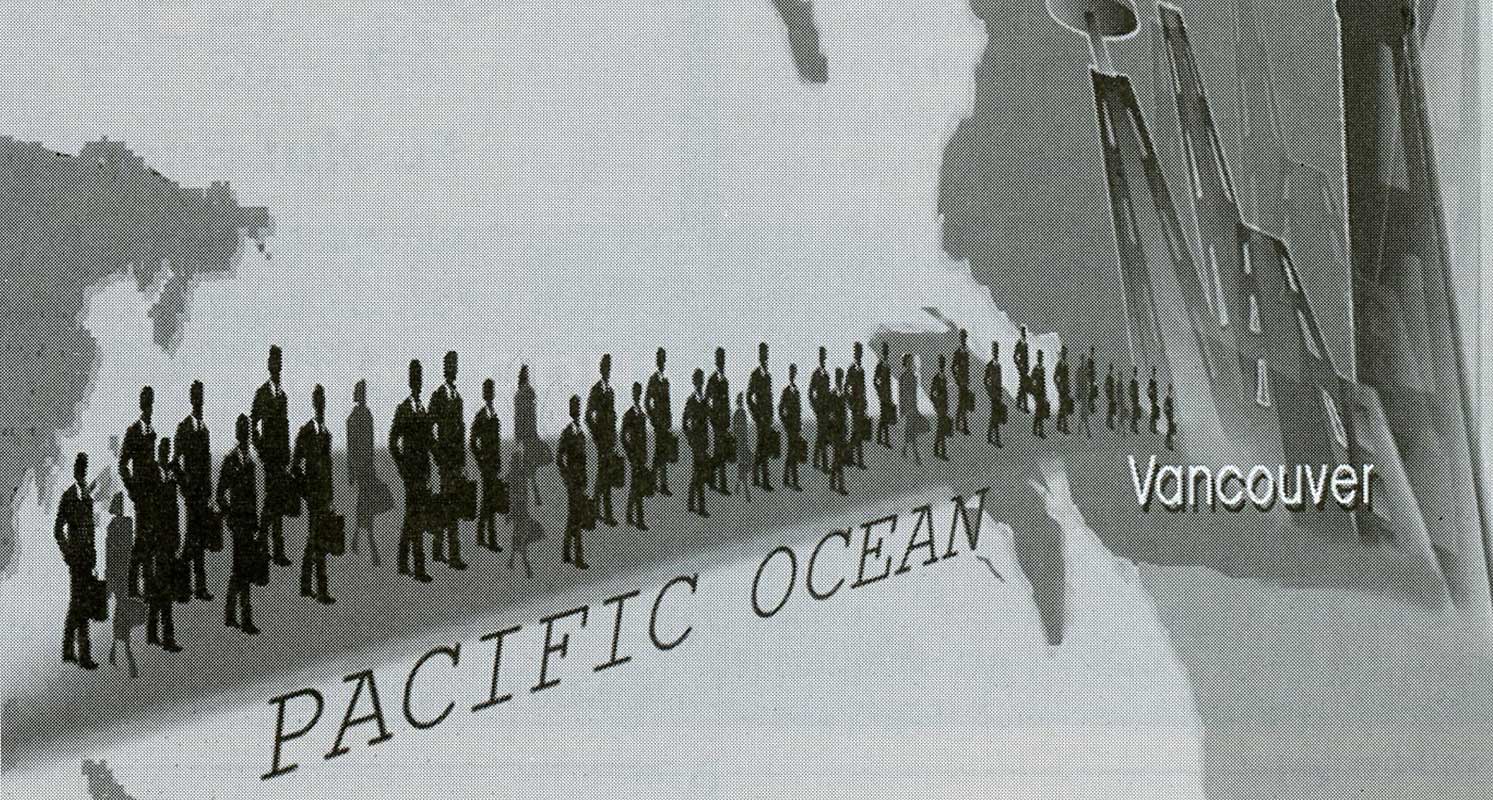

Just after the sun rose over the Pacific Ocean on December 7, 1975, 40,000 Indonesian troops landed on the small island of East Timor, claiming it as the 27th province of the Republic of Indonesia.

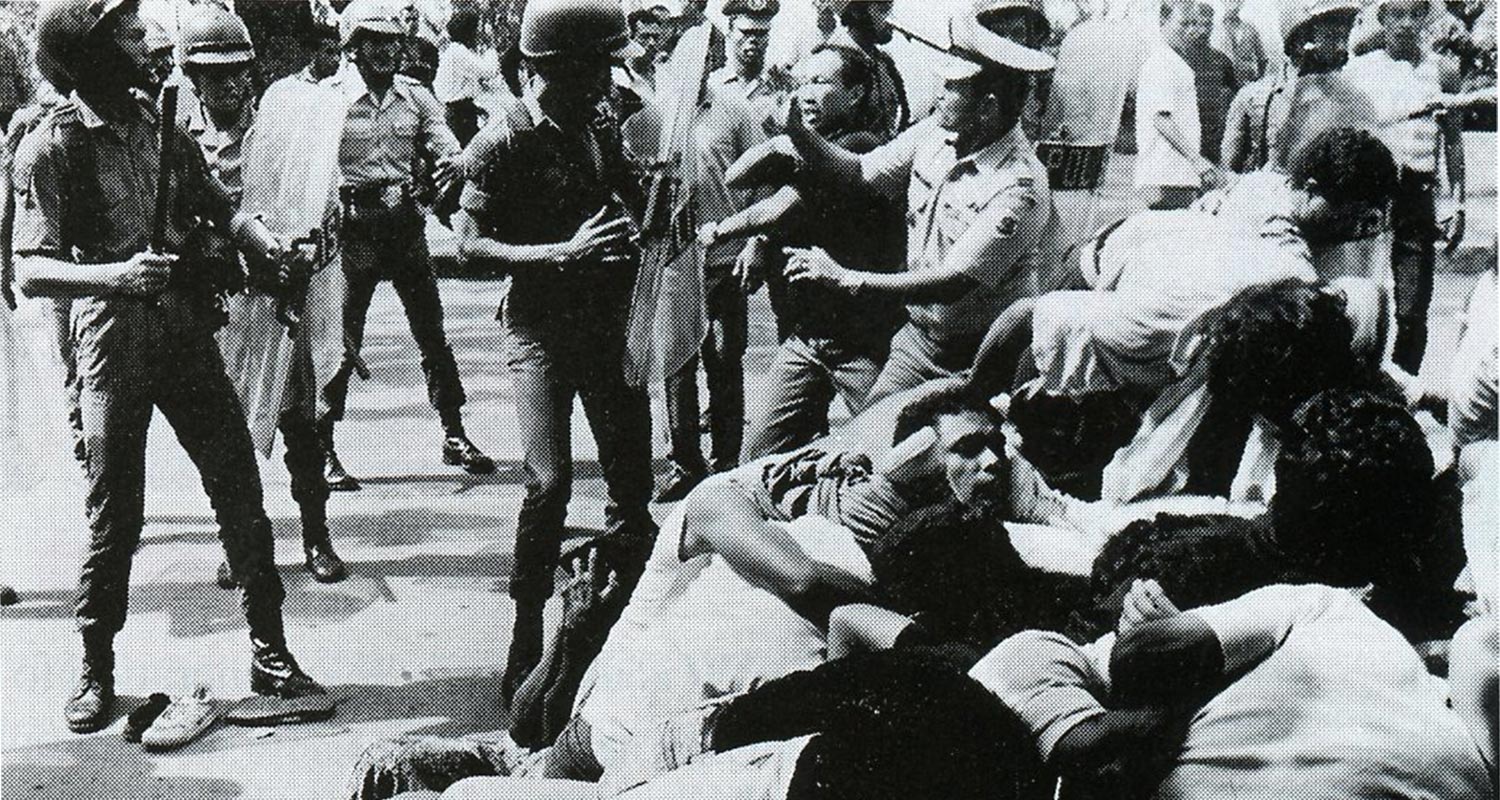

Since then, Amnesty International estimates that the Indonesian military has killed 200,000 people: one third of the population of East Timor. Amnesty also reports that forced abortions, sterilization, torture and mass executions of East Timorese by the Indonesian military have been frequent.

The United Nations quickly denounced the Indonesian invasion by passing a resolution demanding that Indonesia withdraw from East Timor. However, Canada abstained from the vote because of our close economic ties with Indonesia.

Canada’s Involvement

Today, Indonesia is Canada’s largest trading partner in Southeast Asia, with Canada’s trade surplus in 1995 being $65 million. In 1995, more than 100 Canadian businesses sold at least a combined $6 billion worth of products to Indonesia. About 50 of these companies are located in Vancouver. And in January 1996, Prime Minister Chrétien led a “Team Canada” trade mission to Indonesia in which $2.76 billion worth of new business deals were signed. Then, last November, the Canadian government approved the sale of $362 million worth of military equipment to Indonesia by Canadian corporations.

Vancouver human-rights activist Elaine Brière says that the Canadian government and business community think nothing of making deals with Indonesia. The wealthy Suharto regime is one of the most corrupt in the world. Yet, “we are going leaps and bounds into business agreements with Indonesia, through export development credits and other programs,” said Brière in an interview.

“It really shows you the rationale behind going to Indonesia,” said Brière. “But I don’t think it is acceptable. All this money is going out of the country, ostensibly to create jobs in Canada, and there is no evidence that it is creating jobs at all. It’s creating big profits for a few companies.”

According to the Department of Foreign Affairs, the human rights issue in East Timor is “an important element of the bilateral relationship” between Canada and Indonesia. The government’s official stance on East Timor is that development funds from Canada should be “directed to the strengthening of Indonesian efforts in the promotion and protection of human rights in that country.”

Business Community Defends The Country

The business community defends its pursuit of trade with Indonesia by saying that, in the long run, economic growth leads to human rights and prosperity for people like the Timorese. Ron Richardson, the director of information services for the Asia-Pacific Foundation of Canada, says that there should be even more business between Canada and Indonesia. He believes that cutting off trade will hurt Canada more than it will help the people of East Timor.

“Canada is not a big voice,” said Richardson in an interview. “There is nowhere in Asia that Canadian trade is important enough for us to have the leverage to force countries like Indonesia to do things they don’t particularly want to do.”

Richardson, who lived in Southeast Asia for many years, was interviewed by Brière for her recent film Bitter Paradise: The Sell-Out of East Timor. He says that he doesn’t disagree with the assessments of atrocities in East Timor. However, he also says that by Canada helping Indonesia in its process of “economic modernization,” the people of East Timor will eventually benefit. “The best we can do is to help through trading, and playing into the economic development of these kinds of countries.”

Richardson uses South Korea and Taiwan as examples of Asian countries which have become democratic and economically strong through trade with Western countries: “Economic modernization slowly promotes political freedom. It produces an urban middle class that, after a while, expects to have a say in how their country is run. It is a trickle-down effect and the folks at the bottom like the Timorese are going to be the last to get it.”

Human-Rights Activists Are Skeptical

However, many human rights activists like Brière are skeptical of the trickle down theory. “That theory has been around for about 40 years now,” said Brière, “but what do we have because of it?”

“We have at least 40 regimes in the world like the one in Indonesia and there is very little evidence that anything has improved. It is a very weak theory but it is very well accepted. It is a myth, and you have to have a myth to do business with countries like Indonesia, China or South Korea. The rationale is that these countries are gradually going to acquire human rights and become more like us. But does everyone in the developing world have to go through a complete brutalization and breakdown just so they can have some kind of imaginary security in the future?”

Last year, two East Timorese activists, Bishop Carlos Belo and exiled Timorese foreign minister José Ramos-Horta were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, bringing international attention to their cause.

In a March 8 speech delivered in Vancouver, Ramos-Horta suggested the boycotting of Canadian businesses involved in Indonesia. “The businesses of Canada may not care, but ordinary people should,” said Ramos-Horta. “They can tell the government what they think and boycott the businesses that work in Indonesia,” he insisted.

Timorese Resistance

Over the last five years, the blatant massacres of the East Timorese have gradually stopped. But Brière says that this does not mean that the human rights situation has been entirely alleviated. “They do not have these big operations anymore because Indonesia has had to open up to a bit of foreign scrutiny since 1989, and because Indonesia has consolidated itself in East Timor. It is now the most militarized country in the world, and the people are managed through terror. But even if all the killing were to stop right now, the Timorese would remain very bitter. They don’t want the Indonesians ruling them.”

Ramos-Horta also spoke of the ongoing Timorese resistance. “The East Timorese have been told to accept the irreversibility of the Indonesian occupation, but we are still fighting. In January, 6,000 Timorese took to the streets to demonstrate against the looting of their land and the destruction of their environment.”

He noted that economic growth is not the only way to measure the worth of a nation. “Nobody can say that the Suharto regime has not brought economic growth and benefits to East Timor,” he said. “But we find it patronizing that people tell us to look at the material benefits the Indonesians have provided. In the life of a country, you can’t count the moral and spiritual freedom of a people in terms of roads, bridges and high rises.”

Brière adds: “It is asking a whole generation to sacrifice their lives for some future that may never happen. Are these people supposed to sacrifice their lives and their country so that Indonesia can prosper?”

Brière hopes that ordinary Canadians will become more involved with human rights causes: “There is so much corporate money that controls the government here in Canada. But we elect them and pay their salaries, so it is our responsibility to ensure that it is not going to regimes like the Suharto regime.

“In a way, East Timor has done us a service by bringing up our own governments in sharp relief, showing us that they aren’t listening to us, they are listening to someone else. We are going to have to force them to change this.”