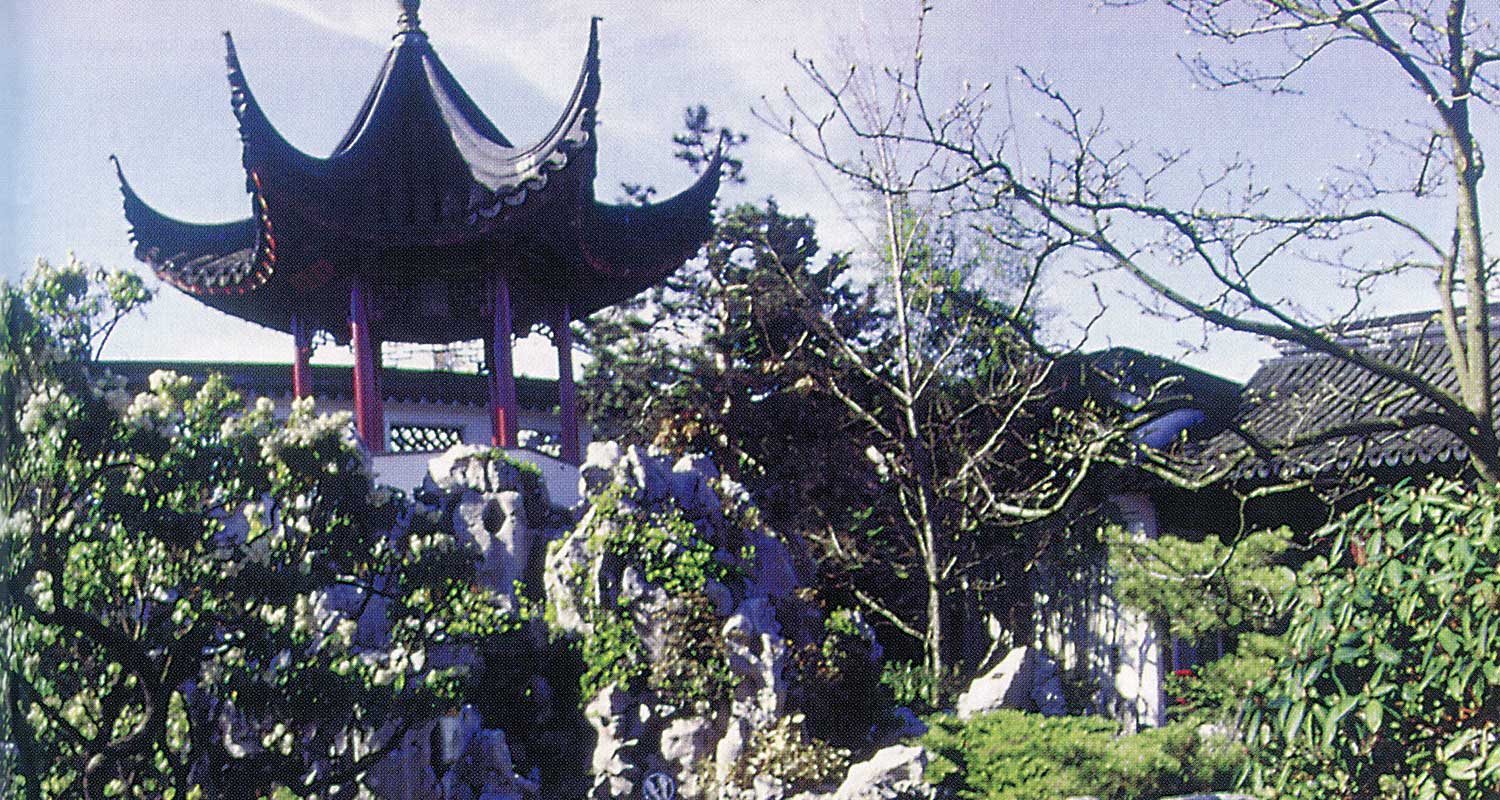

Vancouver is a city of gardens, parks and green spaces. Perhaps more than any other North American city, Vancouver comes closest to attaining the ideal of the garden city, the harmonized balance of urban and natural landscapes. The instinct to green the city came early to Vancouverites. Stanley Park with its scented cedars, expanse of green grass, waterways and clusters of many coloured flowers is almost as old as the city itself. A more recent example of the greening of the city is the Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden which opened for EXPO 86, the first garden of its kind built outside of China.

The Classical Chinese Garden

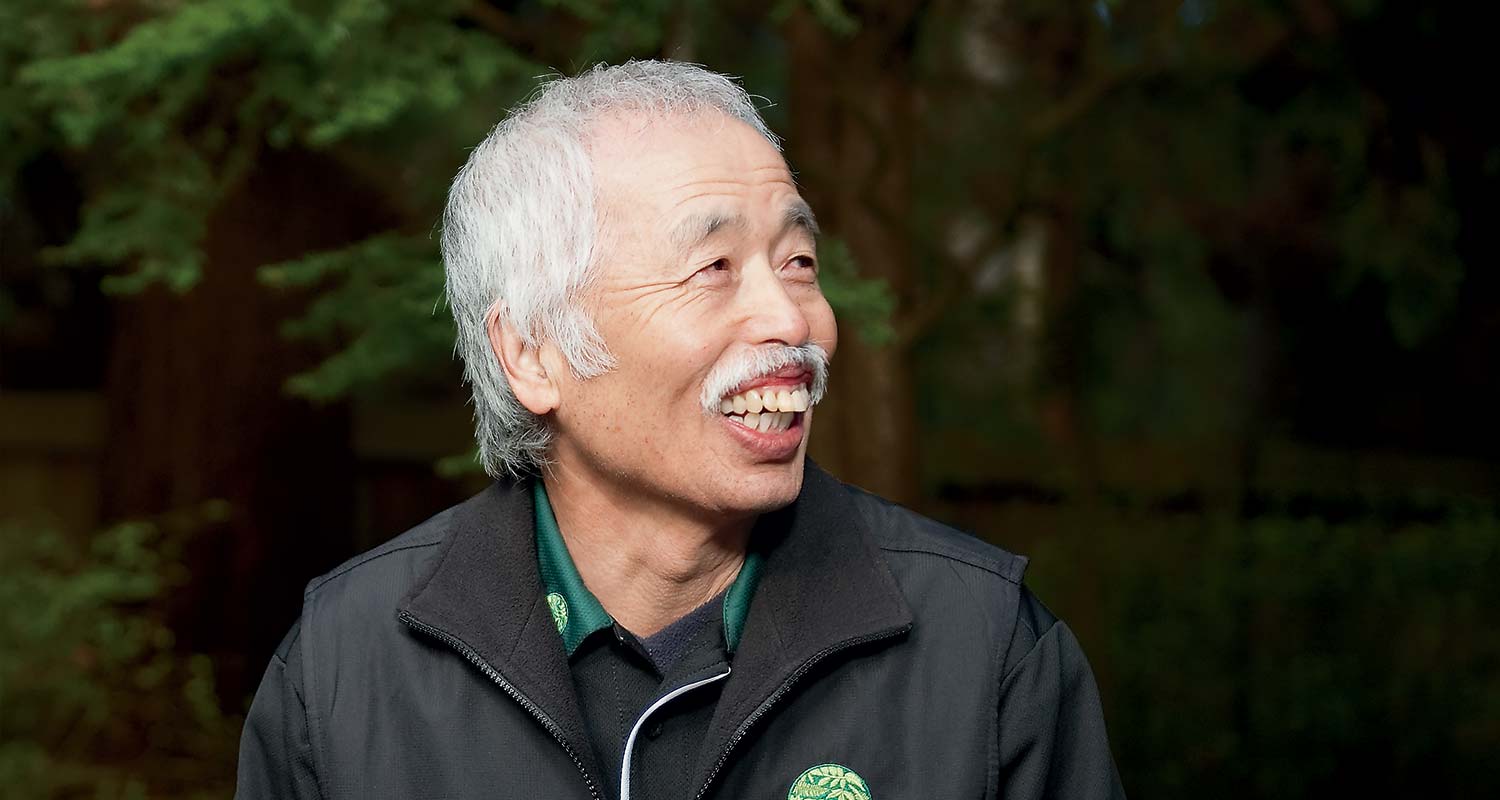

Joe Wai was part of the team that brought the garden to Vancouver and, as the project’s consulting architect, has intimate knowledge of the garden and how it came into being. Born in Hong Kong, Wai immigrated to Canada in 1952. He received his training as an architect at UBC, and after working in some of Vancouver’s most prestigious architectural firms, started his own office in 1978.

Wai explains that the classical Chinese garden is the most complete and immediate expression of classical Chinese culture. The Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden is typical of the types of gardens that were built in the Suzhou area during the Ming dynasty. These gardens were built as part of the palatial homes of scholar-warriors, who Wai likens to the renaissance men of sixteenth century Italy, in that they were accomplished individuals of many talents.

The classical Chinese garden is made up of four basic elements: buildings, rocks, plants, and water. These elements are shaped in accordance with the Taoist philosophy of Yin and Yang. The buildings, inorganic and symmetrical, are balanced against the other elements of the gardens-rocks, water, and plants-which are organic and asymmetrical. The hardness of the pitted lime stones balances the softness of the water. The garden is a dynamic landscape that changes over time. Wai explains that water can, at certain times, be perceived as hard and rocks as soft, depending on the season, weather and perspective in which the elements are being viewed.

A Garden Made From Taoist Philosophy

The classical Chinese garden is, Wai suggests, more contemplative than Western gardens. The Taoist philosophy that shapes these gardens is embedded in them; they are a symbolic landscape that invites reflection and interpretation.

In Taoist philosophy, man is integrated with nature-a small part of the whole. This holism is reflected in the way the gardens are constructed. The natural elements of the gardens, rocks, water and plants are integrated with the living areas. The scholar’s study, the pagodas for viewing and relaxation, the courtyard for listening and performing music, and the main hall are not segregated from, but built in and around the gardens.

Though never a strong tenet of Western belief, holism-expanding the moral community beyond human society-has recently gained attention via the environmental movement. Environmentalists view the crises in the natural environment as rooted in the common modern attitude that nature is a resource to be exploited.

Integrating The Past With The Present

Oriental holism extends not only between nature and man but also between the past and the present. The Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden is representative of an ancient history of development, “building on the capabilities, talents and experimentation of many people throughout the centuries. The gardens are evolution with continuity,” says Wai. The present and past are linked.

Contemporary culture often seems at war with the past. Newness and difference are merited in themselves. It is fitting that the garden came into being as part of a reaction against an attempted bulldozing of the past. The site the garden presently occupies was originally planned as an elaborate freeway connector system through historic Chinatown. This proposal met with stiff opposition from those who wanted to preserve the city’s character and livability. The Freeway Debates, won in favour of preserving Chinatown, were soon followed by proposals to restore and enhance the area. The Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden was part of those early initiatives. Within the context of Vancouver’s history of urban development, they represent evolution with continuity.

The gardens are evolution with continuity. The present and the past are linked.

The greatest contribution of the Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden to Vancouver is its austere beauty, where less is more. Wai recalls that he not only had to learn the Taoist principles that shape the garden, but had to apply them more subtly than his modern sensibilities and training were accustomed to. The paradox that less is more counters modern intuitions about how to enhance life. Modern cultures are cultures of excess. Life for the modern is enhanced by increased wealth, increased possessions, increased status, increased influence and so on. For the modern, if some is good, more is better. The garden, to the contrary, suggests that experience can be heightened by a paring down of one’s environment.

An example of ancient Chinese tradition and Taoist philosophy, the garden seems incompatible with modern culture. Wai disagrees. The Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden is not an aesthetic or ideology out of place and time, but an addition to the city’s landscape that exemplifies thoughtful balance. There is a time for austerity and a time for revelry, for new and old, for urban and natural. The challenge is to create a harmonious interplay between the contrasting elements of life.