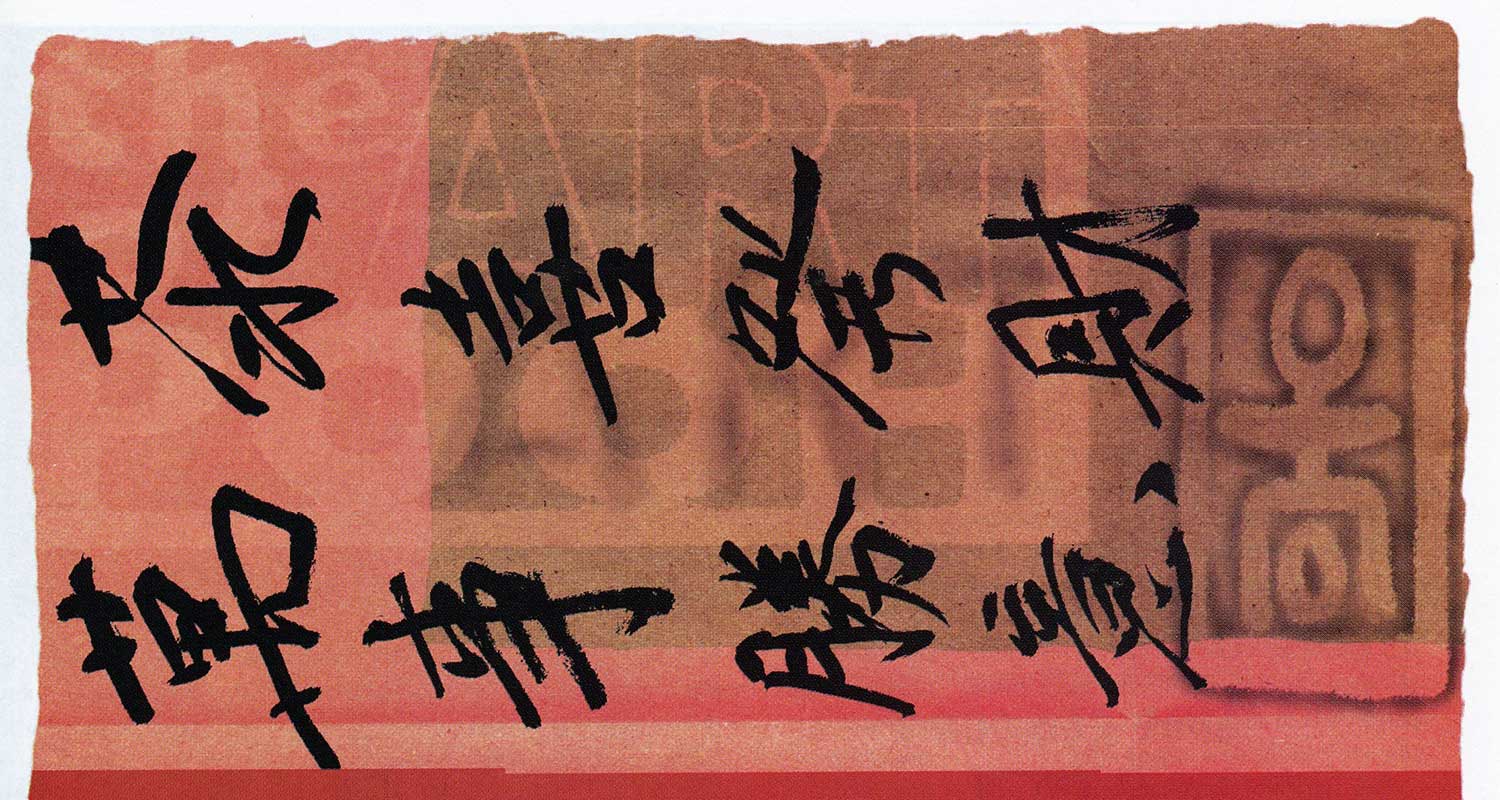

“One can surmise a variety of things about these pieces, there is all kinds of speculation, but there is really no way of knowing what these pieces really mean.” Dr. James Caswell, professor of Fine Arts at UBC and curator of the current Chinese art exhibition at the Museum of Anthropology, is discussing only one of the many mysterious aspects of Neolithic jade artefacts. Thousands of years old, these jades remain a curiosity. How were they made, what do they mean and who were these highly skilled artists? Today, the existence of jades in private and public collections is often surrounded by controversy regarding authenticity, methods of collection and rights of ownership. Nevertheless, Neolithic jades remain truly beautiful-they speak a silent story of art, history, process and politics.

Neolithic Jades

The reverence for yu (jade) was born over 9,000 years ago in the Neolithic cultures of China. The mineral nephrite, more commonly known as jade, is a plentiful stone that was found, as it is today, as boulders in the beds of the Liao and the Yangzte rivers. Nephrite consists of interlocking fibrous crystals of either tremolite or actinolite, which give the stone its strength. Predominantly dark green in colour with white marbling, nephrite can also have inclusions of iron ore which present themselves as rusty orange veins. With time and exposure to the elements, the exterior of the stone turns a reddish brown that can be carved away to reveal dark green insides.

Entombed in gravesites for centuries, even the purest nephrite was destined to discolouration. The mottled rusty brown surfaces were once a bright yellow green, but years of nestling in the cradle of the earth, subject to heat and moisture, has changed these stones from fresh young sculptures to old grandfatherly icons.

Gyula Mayer, a private jade collector, speaks about Neolithic jade with an appreciation born from an interest in modern art and sculpture. He has been studying and collecting Neolithic heirloom jades for over 30 years and admires the highly advanced technical skills of the ancient artists.

Neolithic jade was not actually carved, but rubbed. Mayer adds that “They used some abrasives to remove excess material from the product, and of course it was very time consuming.” Creating the incised lines and buttery smooth surfaces of some of these works would have taken years. To cut a slab, a rope had to be used to slowly slice a stone in two. Bamboo tubes were also used to drill holes through both sides of the jade, as evidenced by ridges that are often found on the interiors of tubes. In terms of technical construction, Neolithic pieces are a feat of endurance and skill. Even today, with the use of electric grinders and diamond drills, jade is a strong material that takes time and patience to shape.

Neolithic Jade Found In Ancient Burial Sites

From recently excavated burial sites, it is apparent that only a few people had the wealth of jade objects. One excavation from the Liangzhu culture revealed a tomb that was literally lined with jade. Who were these ancient people? Did they trade their riches to acquire these pieces? Were they leaders who were given jades out of respect or were they feudal masters who demanded that these pieces be created? These are the questions asked by Dr. Caswell, who is currently on sabbatical to study the most recently excavated tomb from the Liangzhu era.

Valued for its beauty and prized for its strength, jade was used for many types of objects. The three most common pieces found in Neolithic tombs are the bi disc, the cong tube and animal figurines. The cong, or ts’ung tube, is a cylindrical carving with a square cross-section, often showing fine incised carvings. The bi, or pi disc, is a flat disc with a round or square perforation in the middle. Most often it does not have incised carvings.

Who were these highly skilled artist? Can we imagine the spaces in which long hours were passed shaping these stones?

Some experts write that the bi disc represents the sun, or “the round heaven” (t’ien-yuan), and in turn, the cong is meant to represent “the square earth” (ti-fang). These representations and symbols are the language of the Liangzhu, but unfortunately their meaning is largely lost to us. In one tomb, up to 30 cong tubes were found placed around a body with the larger ends pointing toward the head. Two pieces were placed on the chest and abdomen, and as many as 24 pi discs were found underneath the body. It is obvious from the excavations that these pieces were used to protect and accompany the body in transit to the afterworld.

The Life Force Of Jade

Translucent and lustrous, jade has been described as the flesh of the earth. Some strains of archaeological discourse have constructed a complex mysticism around these jade objects. Many commentaries emphasize the mystical properties of the stone. For example, scholars write that the demonic masks on the ts’ung tubes could be the iconography of a trinity: heavenly deity, ancestral spirits and sacred animals. Each entity is linked to the life force, the earth, and to each other. Therefore, any of the three entities could transform into the other as they wished. The ancient concept of kan-ying-empathy between things of like kinds-suggests that the Neolithic cultures may have believed that the jade insignias paralleled the qualities of the objects they were carved to mimic. The Chinese word for “ritual” actually translates as “to serve the gods with jade” which implies that, even in Neolithic times, jade pieces were considered a medium of communication between humans and supernatural beings, between heaven and man.

Are These Pieces Considered Artefacts Or Art?

Both Mayer and Caswell raise questions regarding authenticity and the impact that the pieces have had on the cultural history of China. During the cultural revolution, the Chinese government had little interest in the significance of jade. The government believed that veneration of these objects reflected a traditionalist faith that challenged the political thought of the time. Mayer remembers a time when many Neolithic pieces were destroyed because of such beliefs. As a result, many of these cultural treasures were smuggled out of China, and are now in the hands of private collectors around the world. However, the question remains: who should have ownership of these pieces? Comparative analysis must be used to determine the authenticity of particular pieces. Because there are so many artefacts circulating in private and public collections, it will be some time before a definitive method for authentication can be applied to all collections.

Who were these highly skilled artists? Can we imagine the spaces in which long hours were passed shaping the stones? As an artist, I am curious about the methods of production and the social atmosphere in which these works were constructed. How were these techniques learned and shared among the masters? Were they families who passed insignias and symbols from ancestor to descendant and strove to perfect aspects of technique? Did they have workshops, like we do today, where experts come to teach many willing to learn? Did women and men work side by side to create these masterpieces, or was this artistic practice segregated along gender lines?

On the cusp of this debate is the differentiation between artefact and art object. I look at these pieces from a Modernist perspective, with appreciation of formal and technical innovation, quality of aesthetic power and expression of intense feeling through abstract form. The bold shapes and abstract representations of Neolithic art objects prompt appreciation for a perfectly formed circle, a flawlessly smooth surface and colours that reach my psyche on an indescribable level.

My Western eyes have been trained to see art this way, yet I am hesitant. This perspective has traditionally ignored social and historical issues around art and art making, not to mention the problems inherent in trying to understand an ancient culture through the filter of modern experience. But, through this dangerous distance, I wonder if these are feelings that I, as an artist, share with these ancient masters.

Pacific Rim Magazine and the author gratefully acknowledge the assistance received in the preparation of this article. Special thanks to Gyula Mayer for sharing his in-depth knowledge of Neolithic jades and cultures, to the Museum of Anthropology for providing the photographs for this article, and particularly to Mr. Victor Shaw, collector of Chinese antiquities, Dr. James Caswell, professor of Chinese art at UBC, and Jennifer Webb, Director of Communications at the MOA. The jades of Shaw’s collection featured in this article are currently on exhibition at the MOA, and it is possible that the entire jade collection will be sent to the Museum, to be exhibited at a later date.