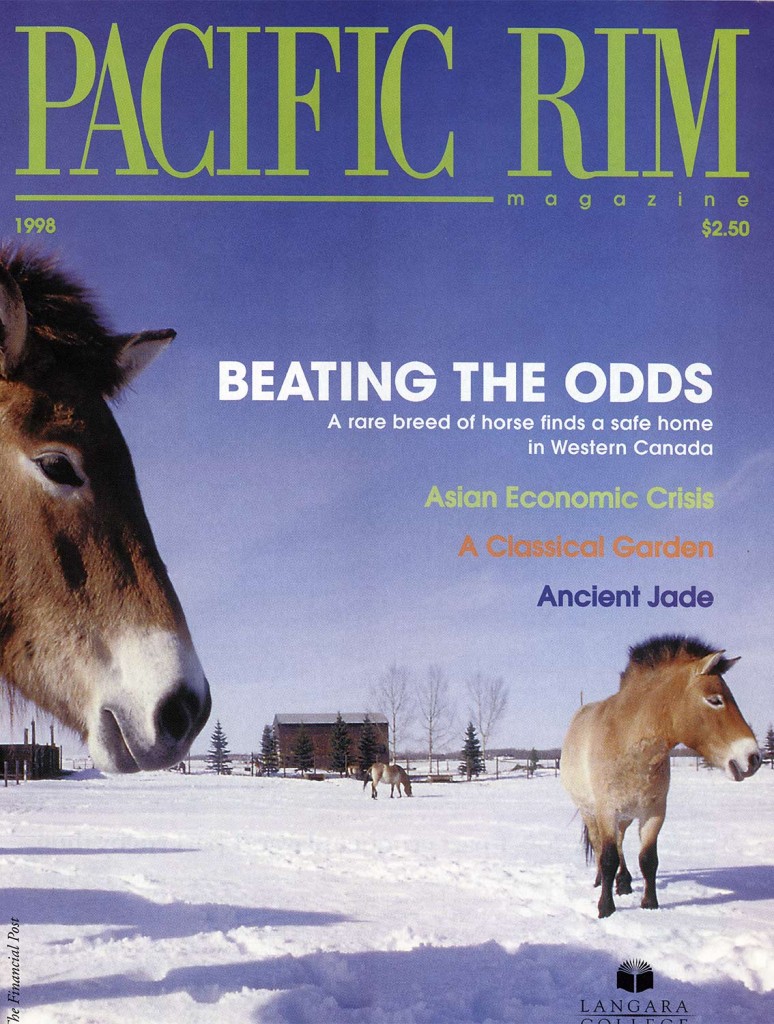

“Handsome and jaunty in appearance as either of her sisters, with their raking masts and clipper bows, she was the beautiful child in a family of three beautiful daughters. She never went aside from the path laid down. No war sinister has marred her escutcheon. No scarlet letter has dimmed her reputation. No wayward current ever influenced her to her sorrow, and no harem-owning kinglet ever won her eye or attention.”

The Sunday Province, Vancouver, July 4, 1926

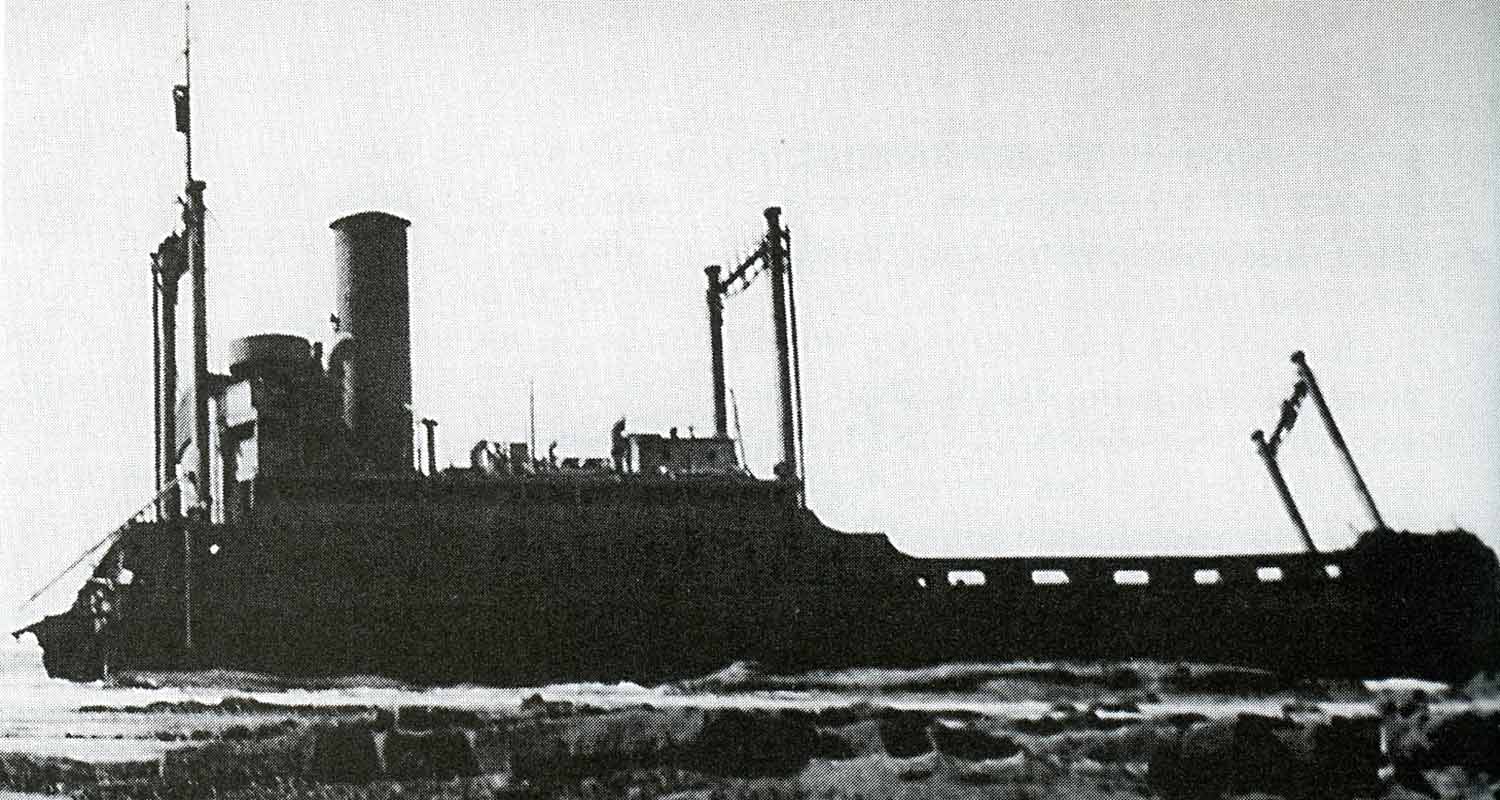

She had crossed the Pacific in high style 315 times. She had been requisitioned by His Majesty’s Armory for service in World War I. She had been the fastest ship on the North Pacific Route. And in 1926, she lay rusting in a North Vancouver, British Columbia harbour.

The Empress of Japan

The Empress of Japan was described with near-biblical awe during her charmed 31-year career. She and her sister ships, the Empress of China and the Empress of India, carried passengers and cargo across the Pacific Ocean, linking Yokohama and Hong Kong to European trading routes from Vancouver. Commissioned in 1889 by Canadian Pacific Railway, the new steamers were symbolic of changing times. Equipped with both a steam engine and full masts and rigging, the ships appeared both modern and classic, caught in the transition between sail and steam.

The Empress of Japan functioned like a small floating city, offering trans-Pacific passengers accommodations in the style of the great passenger liners of the era. The 160 first-class passengers enjoyed luxuries consistent with those offered at CP hotels at the time. Housed mostly on the upper deck, they were privileged with a covered promenade, a smoking room, and the first-class dining room. A smaller dining room and lounge above the upper deck were also open to first-class passengers.

On the main deck were the remainder of the first-class cabins, the second-class accommodations and dining hall, rooms for steerage passengers and crew, and storage space for cargo.

The lower deck of the Empress of Japan housed most of the potential 700 steerage passengers, the bread and butter trade of ocean liners of the time, and the remainder of the crew quarters. Storage space was also ample on this level, and in the holds below.

The Fastest Ship On The North Pacific Route

The Empress of Japan’s route consisted of travel between Vancouver and Hong Kong, with calls in Victoria, Yokohama, Kobe, Nagasaki, and Shanghai. Due to rail delays in Canada, the June 7, 1897 crossing of the Pacific was rushed, and completed in ten days, three hours and 39 minutes, making the Empress of Japan the fastest ship on the North Pacific Route. This efficiency of travel made the once daunting journey from England to Asia seamless, and helped establish the budding port of Vancouver as a destination for East-West travel. As a CPR advertising poster from the early 1900’s reads: “Today whole fleets of palatial steamers of immensely heavy tonnage ply these waters, linking east and west and promising to make Vancouver another Liverpool.”

In 1885, the British Columbia government transferred more than 6,000 acres of crown land near English Bay to CPR, and the Vancouver we now recognize began to take form. The CP railway was extended to Granville, at that time a small town near Coal Harbour. West of Granville, Canadian Pacific built a train station, dock, warehouse, and hotel. A bank and post office followed, and in 1901 a long pier was built in Coal Harbour. The hub of Vancouver’s business district was in place.

The Call For His Majesty’s Admiralty

After more than a decade of service as a luxury ocean liner, the Empress of Japan was pressed into a new role. A clause in the agreement of commission between Canadian Pacific Railway, the Canadian Federal Government and the British Parliament stated that in the event of war, the Empress of Japan would be fitted to meet Admiralty requirements and sail as a merchant ship. Two days before the Empress arrived in Yokohama on a routine trip to Asia, World War I broke out in Europe. The call from His Majesty’s Admiralty was made.

The Empress of Japan unloaded her passengers at Hong Kong-many of her crew were called into service-and was outfitted for battle. She turned from luxury liner to utilitarian war ship; her lounges were emptied and her holds were filled with ammunition. She was fitted with eight guns capable of shooting five miles. Most of her patrol consisted of escorting and inspecting vessels in South Asia and the Red Sea. She did, however, repatriate the S.S. Exford, a British ship that had been captured and pressed into service for Germany. Following World War I, the Empress of Japan returned to civilian duty.

Retiring For The New Fleet

The end of the war also signaled the end of the Empress of Japan’s reign over the North Pacific Route. Outclassed by a new generation of Empresses, she was retired in 1922, left at harbour in Vancouver, and gradually dismantled.

Her name may not be remembered by most, but her legacy will always be greater than the sum of her achievements. More than an ocean liner, more than a link to Asia, the Empress of Japan is one of the few remaining ties to Vancouver’s origins. And though her place in history is secure, she is forgotten, as the city that she helped build passes her by.