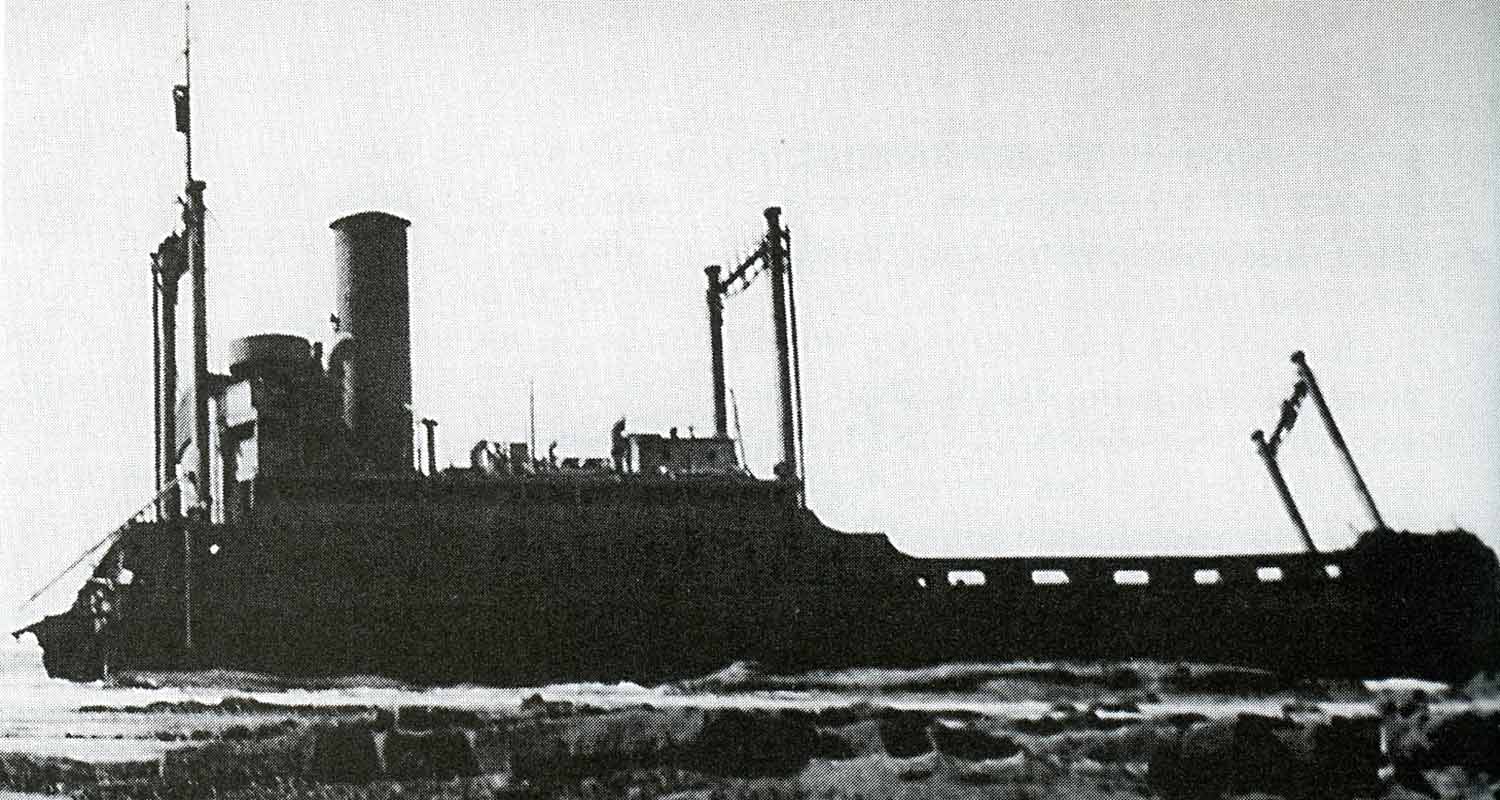

It was the spring of 1943, and a 15-year-old boy took his first summer job at the Pachena Point lighthouse on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Little did he know he would become a witness to one of the area’s last major shipwrecks on record. On April 30, 1943, the Russian transport Uzbekistan lay wrecked on Darling Creek. Due to a gale and poor visibility, she had lost her position, and the strong northern current forced her ashore.

Luckily the 50 crew members survived. But not all of the ships that have floundered on the shores of the West Coast Trail can claim the same. Richard Wells was that 15-year-old boy. Fifty-six years later he still remembers the day the Uzbekistan wrecked, and the ship’s boiler and other machinery are still visible. Today, Wells is the author of A Guide to Shipwrecks Along the West Coast Trail, one of the most referred-to guidebooks on West Coast Trail shipwrecks. Although designed for hikers, his guide is also popular with anyone interested in the history of these shipwrecks. The West Coast Trail runs from Port San Juan, near Renfrew, to Cape Beale. Approximately 80 vessels were wrecked along the trail between 1854 and 1977.

What Was The First Shipwreck On The West Coast Trail?

The earliest recorded shipwreck along the trail is the Brig William. She was wrecked on Jan. 1, 1854, and went ashore eight km east of Pachena Point. Her captain and cook drowned, but the remaining 14 crew members made it ashore. The coastal native people housed them and later took them to Sooke by canoe. Many other unfortunate ships would share the same fate as the Brig William.

Visiting The Shipwreck Valencia

Although Wells has retired from researching and writing about the West Coast Trail, his life-long interest in its wrecks has not diminished. His last time out to Pachena Point was in 1988 when he traveled to the site of the shipwreck Valencia with the son of one of the survivors. The Valencia went down on Jan. 22, 1906, when she overran her position in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The reasons, as with so many other shipwrecks, were high tide, thick weather and poor navigation. “We flew out there by helicopter,” says Wells, recalling his visit to the site. “This fellow was thrilled to visit the spot his dad told him about. He came all the way up from San Francisco to see it.”

The West Coast Trail was originally used simply to hang telegraph line. As a result of the Valencia disaster, however, there was a two-year attempt to upgrade the trail to a full-scale road. But maintenance of the trail was abandoned in the mid-1950s. The telephone had made telegraph lines obsolete, and the need to rescue hapless ships along the trail had diminished.

The West Coast Trail once served as a lifeline for mariners. Bad weather, navigational errors and a shortage of lighthouses contributed to shipwrecks.

Jacques Marc, exploration director for the Underwater Archaeological Society of B.C. (UASBC), says the shipwreck of the Valencia is the most notable in the history of the West Coast Trail. The ship ran into trouble eight km east of Pachena Point while en route from San Francisco to Seattle and Victoria. It was forced against a wall of shear rock and huge waves pounded it to pieces. Tragically, 136 lives were lost. Marc comments, “There’s not even a kiosk to mark the loss at the spot where it happened along the trail.” Having explored the submerged remnants of the Valencia, he recalls how the bow of the ship sticks up from the sandy ocean bed.

More Shipwrecks Of The West Coast Trail

Like the Valencia, the remains of the Michigan can still be seen today. The steam schooner ran ashore on Jan. 20, 1893, 1.6 km east of Pachena Point. Miraculously, only one person died of exposure while seeking refuge along the old telegraph trail.

From a historic viewpoint, the three-masted ship Becherdass-Ambiadass also makes an interesting wreck. On July 26, 1879, the ship was lost in fog and struck shore at full sail. Native people reported the mishap to people in Cape Beale, and a local schooner rescued the crew a day later. There were no lives lost in this shipwreck and very little of the vessel remains today. However, the location of Pachena Point, one of the most dangerous points along the West Coast Trail, and the extent of damage to the ship make the wreck unique. Yet Pachena Point has not always been known by its present name. After the wreck of Becherdass-Ambiadass, the point was named Beghadoss Point, a title derived from the ship’s Parsee name. Only in 1909, when the light station was built, did the point receive its current name, Pachena Point. According to Marc, the most recent shipwreck is the 3Js, a fishing boat that crashed in 1996. All of its crew survived.

The West Coast Trail Is A Ship’s Graveyard

David Stone, executive director of UASBC, refers to the waters of the West Coast Trail as a “Ship’s Graveyard,” echoing the nickname used by those familiar with the area. The most dangerous points along the trail are Pachena and Carmanah Points. In the early days bad weather, navigational errors and a shortage of lighthouses all contributed to shipwrecks and the loss of life. During World War II, lighthouses turned off their beacons to discourage Japanese attacks. Unfortunately, their darkness endangered passing ships that relied on guidance when navigating the coastal waters. In addition, the strong north-setting current becomes more extreme in stormy weather. A ship that does not turn east into the Strait of Juan de Fuca will be swept north into a wall of rock.

In the last few decades, satellite navigation and improved search and rescue methods have reduced the danger of shipwrecks. The Canadian Coast Guard now has a major radar installation on Mt. Ozart, which serves as a navigational aid to ships equipped with radar. From its elevation, watchers can see as far as 160 km out to sea.

Ways Of Exploring The Shipwrecks

For those interested in visiting the wrecks, Marc offers some information regarding diving with the UASBC. First, you need your basic diving certification. The UASBC pairs new comers with more experienced divers. Marc cautions that a new diver may be a little disappointed at first since most wrecks are mainly smashed metal and disintegrating wood. Until you gain experience and understand what you are looking at, it may seem like there is little to see. Stone reminds visitors that it is illegal to remove any item from a ship that has been wrecked for more than two years.

The West Coast Trail once served as a lifeline for shipwrecked mariners and rescuers. One of Marc’s pet peeves is the lack of attention given to interpreting the history of shipwrecks along the trail. “You can look out over the bluff from the trail and see the anchor from the Barque Skagait,” says Marc, who encourages people to visit the area. “The boiler, part of the shaft and propeller of the Michigan are still lying on the reef. Many hikers go along the trail without knowing its original purpose. For many, it is simply an endurance test!” Those who piloted the lost ships of the West Coast Trail knew the test wasn’t that simple.

For more information visit the Vancouver Maritime Museum.