Back in Lisbon the fascists were in trouble. In 1974, revolution toppled Portugal’s old guard and turned over some new ways of thinking – and colonialism wasn’t one of them. Nonetheless, Portugal had controlled the tiny island of East Timor and its people for 400 years. When it hastily abandoned the tiny island in 1975, the East Timorese faced a new set of circumstances – circumstances media critic Noam Chomsky would later refer to as “the worst slaughter since the Holocaust, relative to population.”

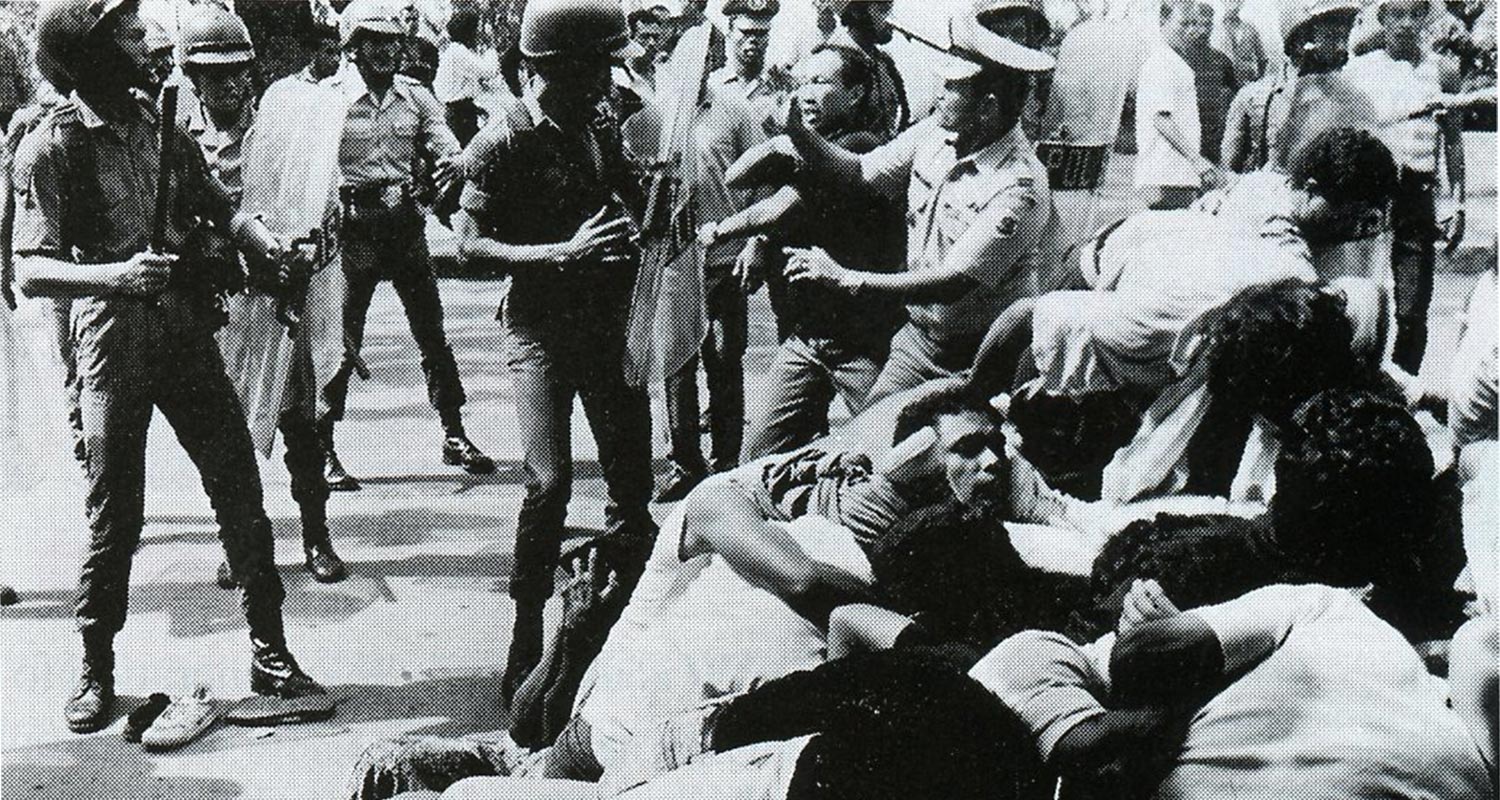

On Nov. 28, 1975, the East Timorese declared their independence under the popular Fretilin party. But, despite 400 years of subjugation, their independence would be tragically brief. Nine days later – on Dec. 7, 1975 – an Indonesian invasion force, 40,000 strong, overwhelmed the fledgling state and swiftly began the violent task of East Timor’s annexation. In the 23 years since, an illegal regime of murder, resettlement, arrest, torture, rape and forced birth control has wracked East Timorese society. Ten separate UN resolutions have decried the occupation. Meanwhile, Amnesty International has conservatively placed the death toll at over 200,000 – one third of the nation’s pre-invasion population.

Media Gains Interest In The Story

East Timor first spurred interest as a political issue when Indonesian troops killed 271 people in front of the eyes of world media. The 1991 Santa Cruz massacre, during which western journalists were beaten, drew attention to the occupation of East Timor and the atrocious habits of the Indonesian military.

What’s news today is the possibility that East Timor is on the road to independence. Amazingly, a quarter-century of violence has not killed the people’s hope. In fact, for the duration of the occupation, hope has been East Timor’s strongest weapon – a weapon that has infuriated the Indonesian military in their efforts to squelch the small guerrilla army and its broad network of civilian supporters. After dramatic changes in Indonesia’s political arena over the past year and U-turns in the country’s policy regarding East Timor, the prospect of a free East Timor has become a possibility.

In May 1998, the resignation of Indonesian president Suharto brought an abrupt end to his three decades of rule by nepotism, graft and oppression. For the people of East Timor, hopes soared with the evidence that Jakarta’s imperialist leanings were shifting.

Freedom Begins To Look Promising

More recently, on January 27, 1999, Suharto’s successor, president B.J. Habibie, surprised the world, announcing that Indonesia would consider granting East Timor independence should the East Timorese reject an offer of wide-ranging autonomy. Two weeks later, Habibie restated his desire to see East Timor free by Jan. 1, 2000, and released Xanana Gusmao, leader of the East Timorese resistance (CNRT), from his Jakarta prison into a more comfortable house arrest.

Even greater hopes ensued in mid-March. At UN-sponsored tripartite talks in New York, Indonesia agreed to a UN conducted plebiscite that would determine the will of the East Timorese. This was the first sign of progress in talks between Indonesia, East Timor’s de facto ruling power, and Portugal, the UN-recognized authority in East Timor.

The indicators of independence have raised high hopes, both in East Timor and around the world. Indonesia intends to offer the East Timorese a chance to accept or reject an offer of broad-ranging autonomy by way of a UN-controlled plebiscite, perhaps in July. Acceptance would give control of the territory’s finances, defense and foreign affairs to Indonesia, giving East Timor control over its own internal government; a vote for independence, which is more likely in a fair plebiscite, would be the first step to nationhood.

One year ago, no one could have predicted this would be happening. Consequently, plans for a free East Timor are skeletal. David Webster is a doctoral student at the University of British Columbia and an authority on Indonesian history and current affairs. Although it would take several years for the East Timorese – in a country so desolated by the Indonesian occupation – to establish and staff a political structure strong enough to stand on its own, Webster believes it could happen given the chance. “Many East Timorese are in exile and active around the world, raising global awareness,” says Webster. “But they are also learning the political skills they hope to bring back to East Timor once they are allowed to rebuild it.”

Plans Are Starting To Form

By most accounts around 20,000 East Timorese live in exile around the world – with the largest groups in Australia and Portugal. Indonesia has claimed that a plebiscite would consult them. With the population in East Timor poorly educated and generally without means, these emigrated East Timorese could provide much needed training and expertise should an independent East Timor emerge. In April, 250 East Timorese academics, politicians and professionals met in Melbourne, Australia, for a five-day conference to discuss the logistics of nation building and develop a blueprint for an independent East Timor. According to East Timorese resistance leader and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Jose Ramos Horta, independence would require a three to five year transition period.

Envisioning around 1,000 to 2,000 UN personnel, Horta predicts that during a transition period the UN would provide most of the support. Economically, a sovereign East Timor would be hard off. But while analysts have predicted that it would cost $120 million US to keep the country afloat, much of the international community has come forward with offers of aid and assistance. When Portugal presented East Timor’s case to the members of the EU in late March, it left with assurance that “significant” monetary support would be given. Meanwhile pro-independence supporters claim East Timor could, in due time, become self-sufficient. Suggested industries for an independent East Timor’s development have included coffee, oil, tourism and marble, which the region has a fine supply of.

The Independence Is Having Adverse Effects

However, the stress of change is showing, and talk of independence is fueling apprehension as well as hope. Violence and tension continue to cause chaos in the territory, and human rights observers claim it has gotten worse since the January 27 announcement. When the secretary-general of Indonesia’s human rights commission, Clementino dos Reis Amaral, visited East Timor at the end of March, he reported the situation to be “worse than ever before.” And now interested observers are measuring their hope and wondering how far Indonesia’s air of reform will carry East Timor and its people.

Whatever the future holds, those who know Indonesia’s past are leery. Webster doesn’t like the phrase: “History repeats itself.” But he predicted months ago “the people to look out for are the people who control the military.” Regardless of the Indonesian government’s professed intentions, the military on the ground in East Timor control the situation. Indonesia is a diverse nation comprised of patchwork islands that has traditionally relied on military might and violence to enforce its interest. Suharto himself came to power in 1965 riding a tide of student protests and civil unrest under the old Sukarno regime. When his cleansing wave of CIA-assisted, anti-communist killings broke, it left behind 500,000 dead people.

So far, Habibie’s provisional government has received international praise for its efforts. He has inherited a country in ruins: 20 per cent of the children in Jakarta, Indonesia’s capitol, are malnourished; 80 million of Indonesia’s people live in poverty. While any successor to the notorious Suharto would have little trouble appearing reformist, Madeleine Albright, U.S. secretary of state, on a visit to Jakarta in early March commended Habibie for the country’s “blooming” democracy. Indeed, Indonesia has relaxed under Habibie: longtime political prisoners have been released, and fair and open elections – unprecedented in Indonesian history – have been slated for June 7 of this year. But the environment for change varies, the task of reform being difficult in a country where the military commands significant political authority under the constitution. While Habibie and his ministers represent Indonesia to the world and undertake policy shifts under their spotlight in Jakarta, the Indonesian military (known as ABRI) and its generals work their intrigues somewhere in the wings.

Military Disturbs The Peace

Groups like Amnesty International welcome Indonesia’s progress, but criticize the military for their subversion of the peace process in East Timor. Random shootings of civilians are weekly, if not daily, occurrences. The difference with the violence now is that the perpetrators have shifted their tactics. Whereas the violence of ’75 and ’76 was carried out in tanks, warplanes and machine-gun fire, the violence today is less overt. With the world eyeing Habibie’s reformist government, ABRI has become more canny.

In October 1998, ABRI began assembling pro-integration militias: ragtag mobs of civilians whose purpose includes policing rural villages and communities and intimidating critics of Indonesia’s presence. Through bribery and intimidation, ABRI recruits vulnerable East Timorese from rural areas, turning them into integrasi – proponents of integration with Indonesia armed with machetes, clubs and the odd firearm. The militias, supplied and directed by the Indonesian military, have caused scores of deaths in past months. They target supporters of independence and their families, and the fear of them has sent thousands of East Timorese fleeing their rural communities for the relative safety of larger cities like Dili, the capitol of East Timor.

While Indonesian foreign affairs minister, Ali Alatas, and Indonesian chief military commander, General Wiranto, have declared the militias are receiving no support from the government, evidence weighs against this claim. A pro-integration militia armed with sticks and knives could conceivably have originated in East Timor, but the chances are they could not have afforded high-tech computer terrorists without foreign aid. In late January, computer hackers from Japan, Netherlands, Canada and Australia launched an attack on the Ireland-based Internet server that houses East Timor’s domain name.

Meanwhile, other sources – including authorities as divergent as human rights advocates, independent journalists, militia leaders themselves and U.S. assistant secretary of state for Asia and the Pacific Stanley O. Roth – find claims of noninterference untenable. The majority of observers recognizes that ABRI, or a rogue contingent of ABRI, is funding the militias, and undermining the prospects for peace by creating an atmosphere of violence and tension.

A Humanitarian’s Perspective

Maggie Helwig is the coordinator of Canadian Action for Indonesia and East Timor (CAFIET), a human rights group that gathers information on human rights abuse in the region and encourages Canadians to take political action at home. Humanitarians in the West have produced hundreds of reports since the occupation chronicling East Timor’s struggle over the years. For over 10 years Helwig has worked for the rights of people in East Timor, and there is a fundamental, underlying hope in her work. But she is worried by the oppressive reality of Indonesia’s military involvement in the territory and comments on their recent methods.

“It is public knowledge that the Indonesian military is arming and encouraging paramilitary groups in East Timor,” says Helwig. “It’s clearly a deliberate attempt to create a level of civil disorder that could prevent any real possibility of peaceful independence.”

The only humanitarian assistance required will be help to bury our dead.

And civil disorder – or war – is exactly what the Indonesian authorities have warned would happen should their troops be withdrawn. Time and again, Indonesia has justified its large military presence with the claim that East Timorese society is divided against itself: with integration supporters on one-side and independence proponents on the other. This said, Indonesia has been conspicuously opposed to allowing the UN a permanent presence.

Horta, who won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1996 for his activism, believes 95 per cent of East Timorese desire independence from Indonesia. He equates the Indonesian claim that a troop withdrawal would risk civil war, with the claim that Jews would have killed each other if “Hitler had not slaughtered them first.” Resistance leader Gusmao points out that the militias never existed until October of last year, when ABRI created them. But they certainly exist now.

ABRI’s goal of inciting the guerrilla forces into violent reaction has proven difficult. In their efforts to prove their commitment to the UN process, the armed wing of the East Timorese resistance movement, Falintil, obeyed Gusmao’s appeals for pacifism in the face of the brutalities committed by the militias. During the cease-fire, which Gusmao brokered in February, Falintil, consisting of between 500 and 1,000 men and women, avoided conflict with the 10,000 militiamen and 20,000 ABRI troops that continued to attack civilians. Peaceful demonstrations were suspended, and through press releases and meetings with the media and world governments, Gusmao sought a UN police force for East Timor. By the end of March, however, the resistance fighters’ patience was deteriorating, and Gusmao warned that, should the situation persist, “the only humanitarian assistance required will be help to bury our dead.”

On April 5, Gusmao gave in. He grimly allowed the resistance forces to resume fighting in defense of themselves. The Indonesian backed squads were on an ambitious campaign of death – a grenade attack on a church full of refugees killed dozens. As the international community winced at the sting of Gusmao’s call to arms, a 23-year-old struggle resumed. Now, while East Timor moves somewhere into the future, it is unclear the struggle for a free East Timor will even reach the UN ballot boxes.