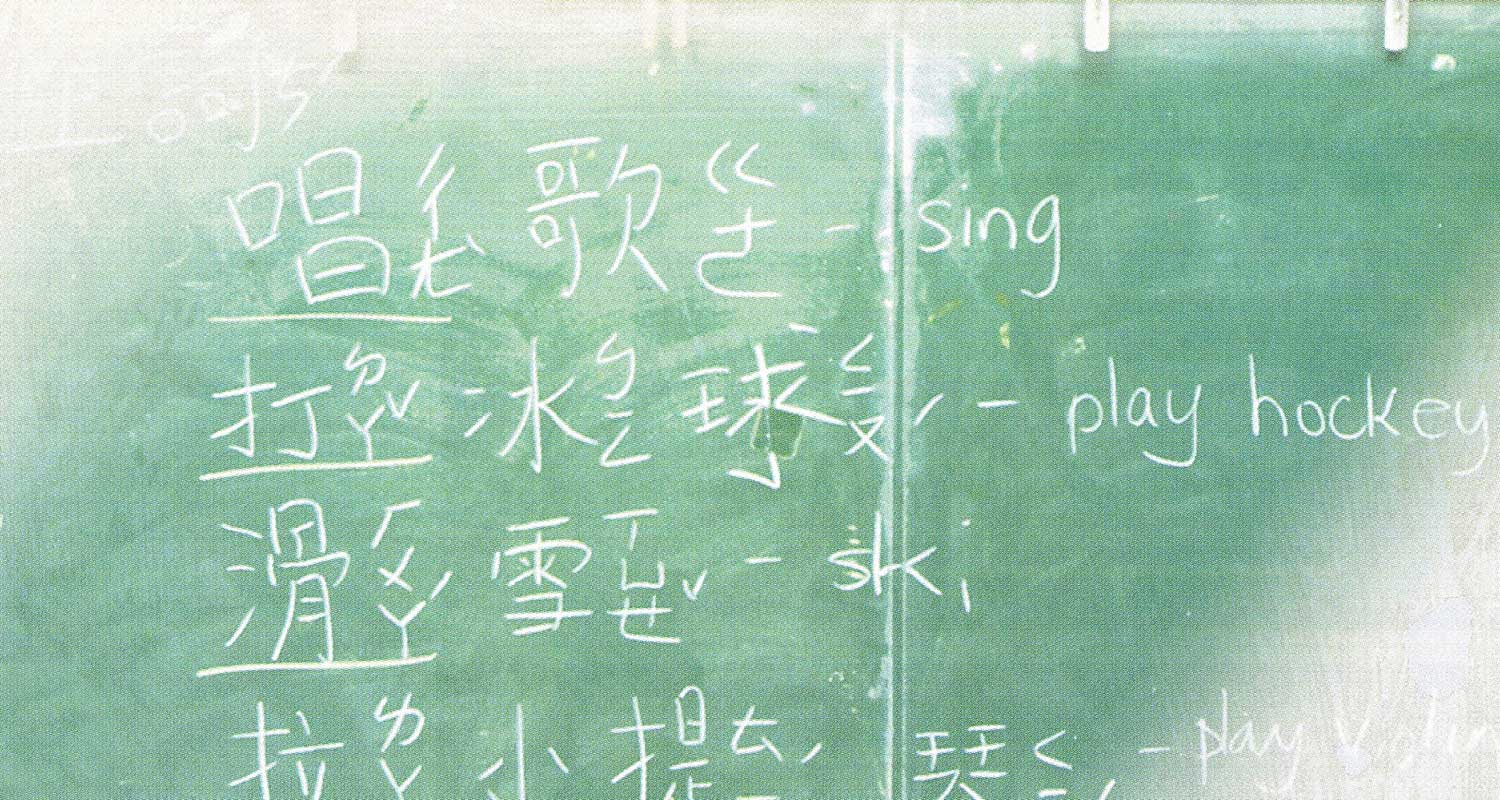

Something special is tacked up alongside the paper-bag puppets and construction-paper flowers that decorate the walls of Dr. Annie B. Jamieson School. Created with crayons and felt markers, beautifully illustrated poetry is on display. In many ways it is like the art found in other Vancouver elementary schools. Yet there is a difference. On a number of the Jamieson school projects, Chinese characters sit side by side with English text. They both recite the same poem, perhaps about the beauty of a tree or the sky.

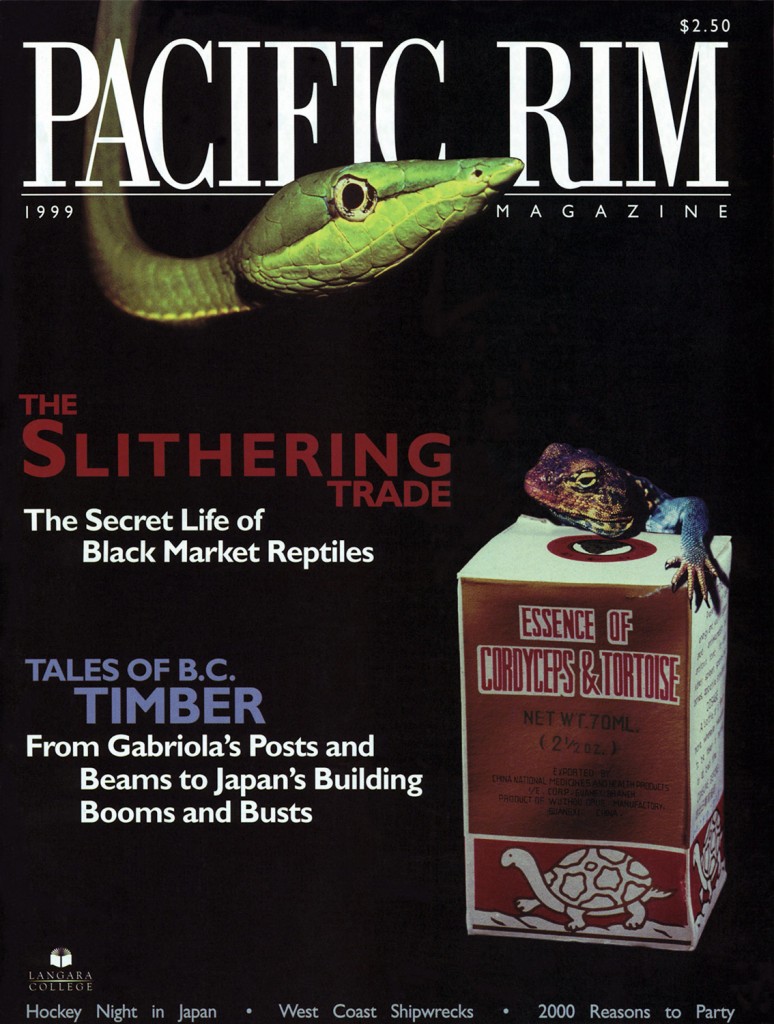

These poems reflect a hybrid of cultures, like Jamieson itself. Jamieson’s Mandarin Immersion Program is opening new doors in second language education by offering an alternative to French immersion. Designed for non-Mandarin speaking students, the program represents Vancouver’s expanding connection to the Pacific Rim. The official language of Singapore, Taiwan, Malaysia and the People’s Republic of China, Mandarin is also spoken by many Vancouverites. School principal John Barton believes students benefit from exposure to such an important language (Mandarin is spoken by more people in the world than any other language). At Jamieson, students learn to speak Mandarin, and to read and write Pinyin and Chinese characters. According to Barton, who oversees the program, this unique opportunity exists because of the perseverance of dedicated parents and teachers.

How The Program Got Started

“Out of parent discussions, we realized there were a lot of people who liked the idea of children acquiring a second language through an immersion program,” says Barton. “But they weren’t necessarily wanting French.” Based on a French immersion model, the program divides instruction time equally between English and Mandarin. In order to reassure parents that their child’s progress in English will not be jeopardized, the school is careful to only admit children with strong English skills.

Barton believes this cautious approach is the wisest one. This attentiveness gives teachers flexibility when adapting and fine-tuning the program. New students also have more time to acclimatize to a language that has a very different structure and organization from the English language. Just learning the unfamiliar tones of the Mandarin language can be a tricky process for beginners. Barton is candid with the parents and children he meets during the application process. The program is not for everyone, he tells them. He also explains that the program will not necessarily make students fluent in Mandarin. Instead, the focus is on developing communication skills and enriching the child’s personal growth. Learning a second language can give the students a competitive advantage later in life, whether in educational pursuits or in their careers. They achieve an extra skill and the ability to communicate with a broader range of people. He believes these elements entice parents to enroll their children in the program.

It Hasn’t Been Easy

Despite strong support and interest from parents and teachers, the program has experienced problems. The Vancouver School Board approved the program on the condition that there would be no additional cost to the board. “Quite honestly, the program has been run out of Jamieson without a lot of school board support,” Barton says, shaking his head. “Part of my job is to get the school board to take over ownership of the program, to try and get more resources and support, and get them to look at it as any other immersion program.”

Finding resources and support has proven difficult. While French immersion programs enjoy translations of up-to-date teaching resources, the same is not true for Mandarin immersion. According to Barton, the appropriate supplies and resources just do not exist in many cases. He credits the Mandarin immersion teachers with finding solutions that overcome this major obstacle. “Our teachers have had to do a lot of digging. Just identifying and acquiring suppliers and resources has been a major job. They’ve done it, but it’s taken a lot of extra work,” he says.

The Truth About The Program

Trying to describe the students’ reactions to the program, Barton beams as he talks about each grade. He repeatedly refers to them as a “really nice group” or “a lovely bunch of kids.” Some grades have bonded and adapted more quickly than others, but Barton doesn’t feel this reflects on student success. He likes to see an official mechanism created by B.C.’s Ministry of Education that will enable Jamieson teachers to monitor the progress immersion students make in their Mandarin studies. At present, the province can only evaluate Jamieson’s Mandarin immersion students for their work in the regular curriculum. However, Barton insists that when he compares students in the immersion program with those in the regular program at Jamieson, he finds the Mandarin immersion students do “every bit as well.”

“I was surprised to find that quite often it’s the child’s choice to come into the program.”

Teacher Flora Chen has been with the program since it began in 1994. Before moving to Vancouver to teach at Jamieson elementary, Chen was the Mandarin subject leader in a heritage language program in Toronto. There she served as a bridge between teachers and the community in a program designed for children already familiar with Mandarin. At Jamieson, however, her classes are much different. While some of her students have grandparents or relatives who speak Mandarin, others have had no exposure to the language prior to entering the program. She appreciates the different philosophy at the heart of the Jamieson program. Unlike a heritage program, which mainly serves children of Mandarin-speaking families, it attracts students who might otherwise never have an opportunity to learn Mandarin. Chen enjoys the enthusiasm she sees in her students. When the lunch bell rings and the children file out into the hallways, they can be heard chatting in English and Mandarin with the kind of ease and playfulness only children possess. “I was surprised to find that quite often it’s the child’s choice to come into the program,” she says, adding that consultation with the parents beforehand is essential to ensure student success. Children adapt at different rates, and contact with parents is crucial to ensure that students don’t fall behind.

Integrating The Immersion Students With The Rest Of The School

Both Chen and Barton agree that integrating the immersion students with the rest of the school’s population is very important. They emphasize to the children that they are not just Mandarin immersion students – they are also Jamieson Elementary students. This approach has the same flavour as the program, which also promotes integration by teaching the immersion students about more than just the mechanics of the Mandarin language. Students also learn about the cultures that speak Mandarin. “You can’t separate language from culture,” Barton stresses. “You just can’t.”

Likewise, school events often revolve around different cultural holidays and celebrations, exposing Jamieson’s regular program students to other cultures. Barton cites the Grade Four math class as an example of integration in the classroom. “The Grade Four teacher doesn’t have her home class, she’ll have a third of the Mandarin [immersion] kids, a third of the regular kids, and a third of the ESL kids. We’re always trying to engineer opportunities to mix the children.”

For Chen, integration is a means to apply developing language skills. Since the immersion students generally come from homes where no one speaks Mandarin, any opportunity to practice is invaluable. “Teaching them is quite easy, but for the students, because they don’t have the natural environment, the school has to provide them with an environment. Being out of the community is very difficult.” As a result, the school created a buddy reading program. Mandarin immersion students meet once a week with the school’s Mandarin-speaking ESL students. “It’s like an exchange of sorts, since that’s the only interaction they have with someone who speaks the language, aside from myself and the other teachers,” explains Chen. This kind of interaction and creative problem solving has proven successful. The students’ friendships with Mandarin-speaking ESL students and their handling of the more subtle elements of the language, such as poetry or humour, suggest that the classroom experiences extend out into the real world. The language skills that children exchange with each other on the playground are as valuable as those they learn in the classroom.

Children Seem To Be Enjoying The Experience

For Barton, one particular example of the program’s success has remained firmly entrenched in his memory. A Mandarin-speaking visitor had come to the school and met with two of the children after class. Barton overheard them speaking in the hallway, and what he heard both shocked and pleased him. The girls were not only talking and responding to the visitor in Mandarin, they were exchanging a joke. Barton laughs as he recalls the incident. “I think it’s great that these kids were feeling comfortable enough to make a joke,” he says with a broad smile. “You don’t make a joke, you don’t get a joke, until you understand the language.”