My favourite memory of my father is the two of us sitting at our kitchen table in Victoria one rainy Saturday afternoon, clipping and snipping away at a tiny Mugo pine. My father, passionate about oriental arts, and I, aged six and curious about the miniature, sat silently for hours crafting the would-be bonsai. We revelled in the creation of this delicate beauty—something in between fine horticulture and fine art. It was meditation.

Since that time, some 15 years ago, I have longed to create a bonsai once again. This is, in part, because of my desire to revisit old feelings, but also to experience the joy of living art.

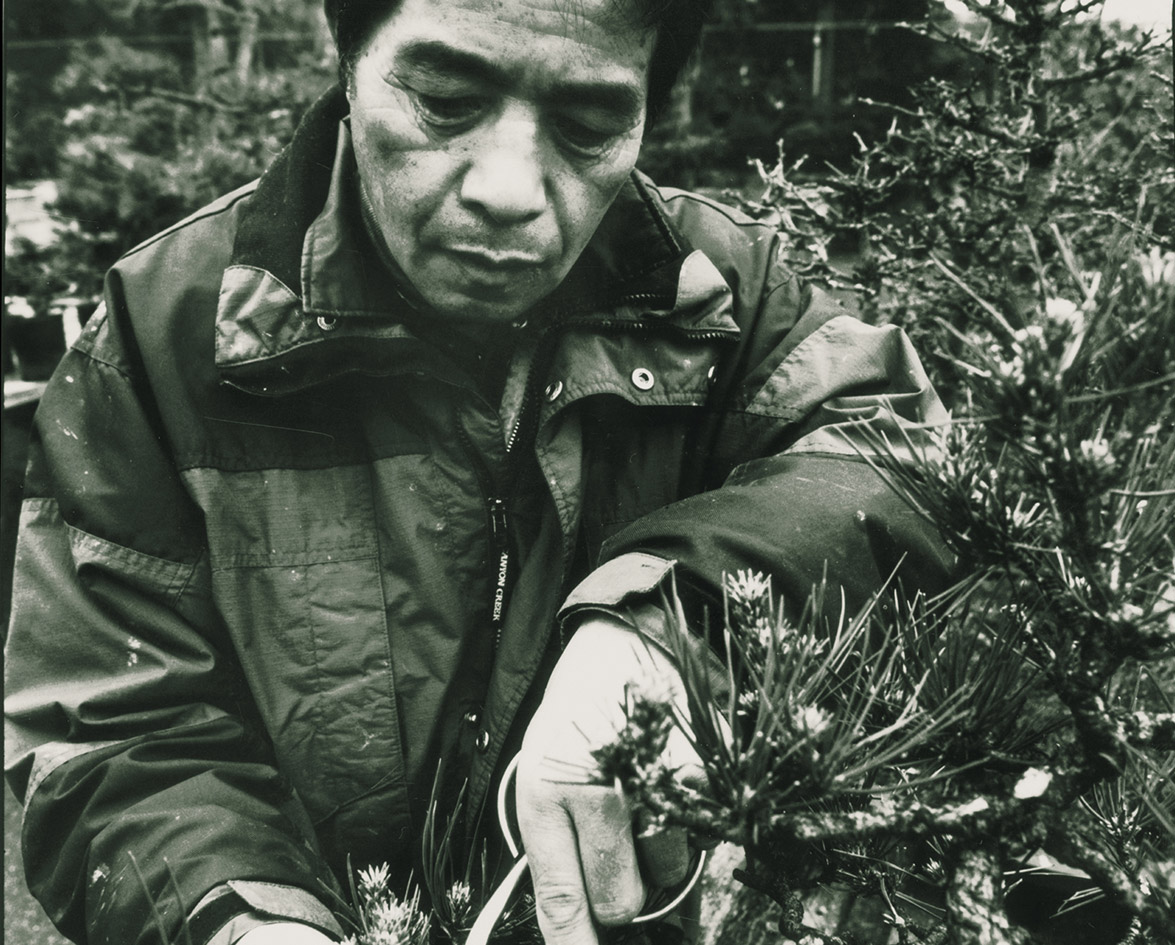

Here begins my dilemma: as I mentioned before, the last time I touched a bonsai I was six. My skills were a little rusty, and I was going to need some help. So I called upon Tak Yamaura, owner of Japan Bonsai, a local shop dedicated to sales and instruction.

The Bonsai Process

I wandered into his nursery on a rainy Thursday morning and immediately felt at peace. In the silence of the garden sat hundreds of tiny trees. All were in different stages of the bonsai process. Some were gnarled and ancient looking, others were still in training wires. This is what Tak says he enjoys the most, “I like the process, start to finish. It’s actually never complete: seasons and form are always changing.”

We sat and discussed the large bonsai phenomenon in the Northwest. In the Vancouver area alone, there exists two clubs devoted to bonsai. The West Coast Bonsai Society and Taguchi Bonsai Club are both part of The B.C. Bonsai Club Federation. To federation members, it is as much about socializing as it is about the hobby. For Tak, it is about creativity and the cooperation of people.

The first step to becoming involved in bonsai is to try making one yourself. The process is very involved, but Tak sent me in the right direction. Start by picking out a tree. You can acquire one basically anywhere (a garden shop, a specialty bonsai store, even your own backyard), but there are several things to keep in mind: bonsais are generally kept at heights between 10 cm–1.3 metres. Evergreens native to the Northwest are the easiest to sculpt. Finding a tree with a nice thick trunk, healthy foliage, and a good root system is important. Tak helped me pick out a juniper, about 25 centimetres high, with a thick corkscrew trunk.

The next step is to pick out a pot. Bonsais must be planted in pots that are shallow, complete with large drainage holes. Ceramic pots are preferred. Aesthetics are important in this process, especially concerning the pot. It has to suit the tree; if a tree has a “feminine” look, give it a pot with a round, soft shape; if the tree has a “masculine” look, give it a pot with a strong, rectangular shape. I decided my tree was without gender and settled for a rectangular pot with rounded corners. How’s that for a compromise?

Before I actually got started, there was one last thing to consider: the soil. Traditional soil is not used when growing bonsais. They grow best in soil that looks like tiny clay rocks, specially made for bonsais. Tak happened to have a concoction of his own made up of 50 per cent lava chunks and 50 per cent pine bark. He sifted out the smaller bits and used the remainder to achieve the best absorption and drainage possible. To avoid losing the soil out of the drainage holes, cover them with squares of plastic mesh and anchor them with aluminum wire. The wire can also be used to anchor the roots.

Other supplies I needed included aluminum wire for shaping the trunk and branches, branch/root cutters, wire cutters, and a sealant. Applying a certain sealant to freshly cut branches will not only reduce the risk of the tree being infected by fungus, but it will also speed up the healing process.

Branching Out On My Own

The time came for me to venture out on my own and begin the process of creating my bonsai. I spread all the supplies out on the kitchen table and began to shake the roots free of dirt so I could see where to begin clipping. My tiny juniper felt so fragile in my hands that I was afraid to cut freely at its lifeline, let alone the sprigs it had for branches. The good thing about evergreens however, is that they are virtually indestructible. I continued cutting.

Roots trimmed and pot prepared, I placed my tree in its new home and contemplated the shape it would take. The trunk had already taken a slightly spiralled look, and wiring the branches to follow the shape became a natural process. Three hours had passed and I hadn’t even noticed.

My final product pleased me. The once bushy, young juniper looked ancient and wise. Having spent hours with my hands in the soil, pruning, sculpting, and savouring the smell of nature, I truly felt fulfilled.

My bonsai now sits peacefully on my balcony, a constant reminder of the simplicity of nature. It requires little maintenance. I prune and water now and again, and eventually I will remove the training wires. Now I have a feeling that my bonsai would like company—and I think I’m addicted.

For more information visit: