On a sunny day in 1945, Aya Higashi [née Atagi] sat crying in the deserted sanctuary of Saint Andrew’s United Church in Kaslo, B.C. She faced a monumental decision that would affect her entire family. She had less than 48 hours to sign papers that would “repatriate” her to Japan, out of the province of her birth.

Recalling this time, Aya said, “How could I be repatriated to a country to which I’d never been and of which I’d never been a citizen? I was a Canadian. That was not repatriation; that was expatriation, and they are entirely different things.”

This was one of the many trials that Aya confronted as a Japanese-Canadian in one of British Columbia’s World War II internment camps.

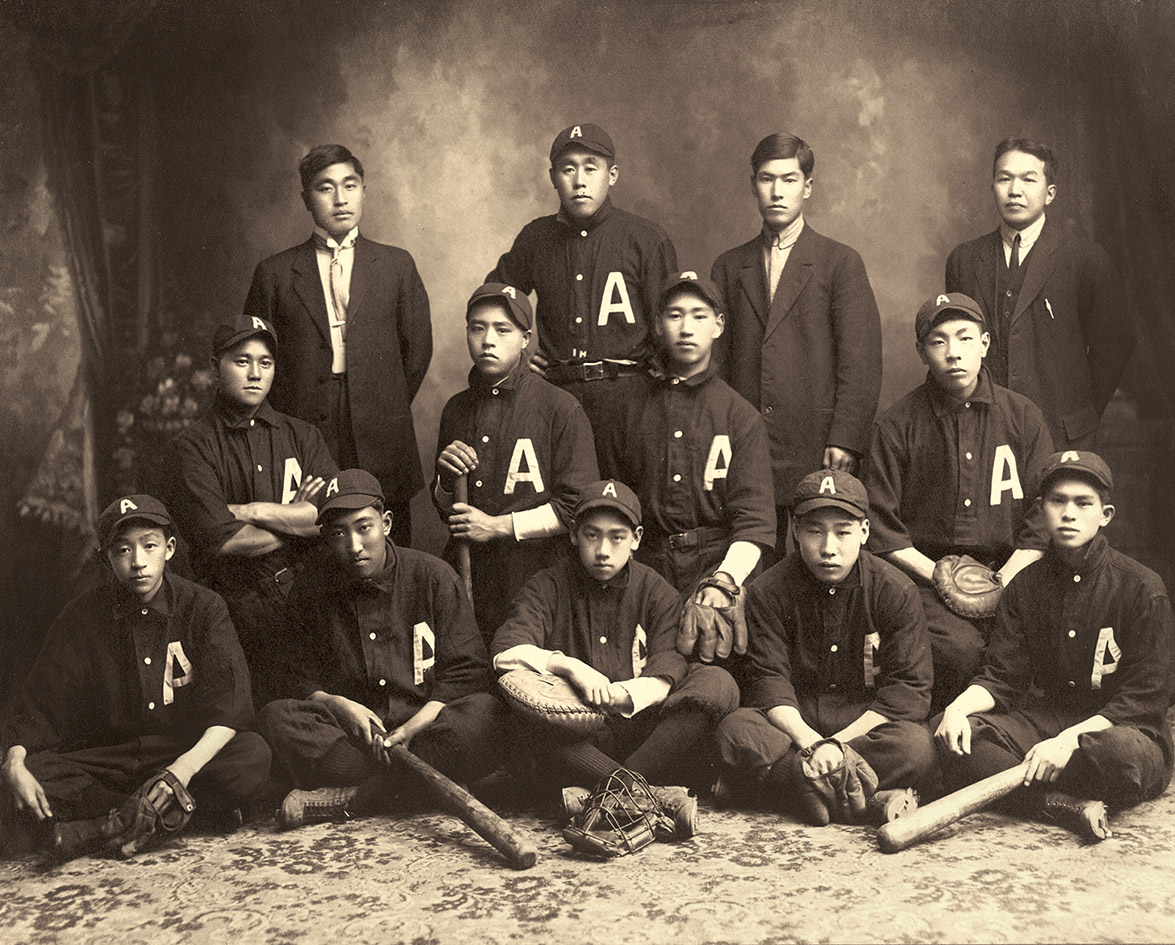

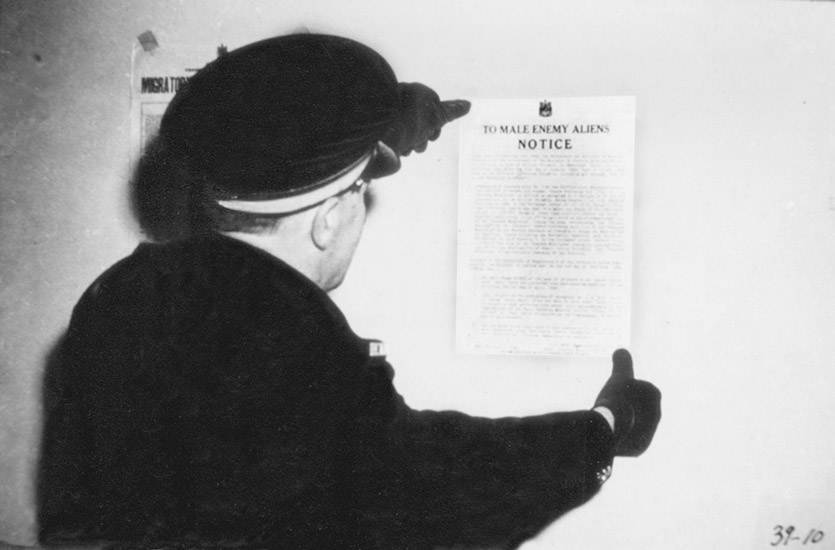

Japanese Canadians Are Ordered Out Of Their Homes

Aya’s father, Kiyomatsu Atagi, had come from Japan to Canada in the early 1890s. After a series of hardships, including being press-ganged into railway work, he eventually made his way to the Pacific coast and became a naturalized Canadian citizen in 1903. He married a young Japanese woman and they had three children: Kimi, Aya and Yute. The family settled in their home on Quadra Island, and prospered until war spread. “The RCMP came to the door…the day after Pearl Harbor, and Dad was ordered to take his three boats to New Westminster. In early March 1942, they told Mom and Dad to pack enough to be away for three months. They were to be on the Union Steamship for Vancouver the next day.”

Like others in the Japanese-Canadian community, the family did what was asked of them. The Atagis packed up, leaving family heirlooms, mementos, and photos behind. They were sent to Hastings Park where they remained until October 1942. “You didn‘t have much time to think and you were hustled here and there. If they didn‘t show up for dinner, the families knew that the men had been taken into work camps. We were supposed to be sent to an internment camp, but not until my parents signed over all of their possessions to the British Columbia Security Commission. I remember crying to my father, asking him ‘Why is Canada doing this to us?’”

The Atagi Family Is Sent To A Ghost Town

Finally, the Atagis signed and were sent to Kaslo, then a scattered ghost town. “The houses had no insulation, the windows had been smashed or boarded up, and in most homes the plaster was falling off the ceilings. One thing that disturbed me was the misconception by some people in the white community that we Japanese were living the high life, and that we were given housing while ‘their boys were off fighting.’ Many Japanese boys tried to enlist but were denied. “We had to pay for our lodgings, and prior to leaving Hastings Park, the government had frozen everyone‘s assets. It was a real struggle to make ends meet. Most of the men had been separated from their families and were away in work camps. Some men remained and worked at logging for 25 cents an hour. This provided wood for Japanese families. Whole families were packed into single rooms, many sleeping on a single straw mattress.”

Aya Begins Educating Displaced Children

Kaslo‘s population of 500 swelled with the addition of 1,100 Japanese internees. With no provisions for educating the children, it quickly became apparent arrangements had to be made. Ten young people with high school diplomas were identified as suitable teachers, Aya among them. “I was paid 25 dollars per month for teaching and, out of that, I paid my lodging and bought school supplies. There was no place to put the students so we rotated between various spots in town. Eventually, the Legion offered us space to conduct our classes in the drill hall. In time, we were also given discarded textbooks. Within a year or so, the local high school made room for some of the senior students.” With all the senior students at the high school, and the Japanese elementary classes moved into the Geigrich building, Aya took the opportunity to hang the Union Jack and Red Ensign flag above her blackboards.

“I was reported to the RCMP by someone who said I didn‘t have the right to hang the flags in my classroom. The RCMP officer told me to remove them. I was very upset—‘No sir, I will not take down those flags. I am a Canadian citizen and I have every right to hang those flags in my classroom, if you want them down then you will have to find a ladder and take them down yourself’—I got to keep my flags.”

Aya And Her Family Face Repatriation

In 1945, there was a growing national resentment towards local Japanese people, and the movement for repatriation to Japan began. Most Japanese-Canadians faced repatriation to a country they had never visited, or a forced dispersal to mid-west and eastern Canada. It was a busy time for Aya. As well as teaching, she looked after her brother and gave blood for the transfusions her ailing mother received at the local hospital. Her father was in Crowsnest Pass, working for the CPR. One Friday, an officer arrived with repatriation papers. “I put off signing the papers because of Mom’s illness, and I had no way of communicating with Dad. Censorship was in place and even if there had been time to send a letter, his response would have come back in shreds. I was so distraught making a decision that would change all of our lives. “I sat in the church overnight and wept and I scribbled all over that paper outlining my reasons why I shouldn’t be expatriated—that I was signing under duress—and explained my family‘s situation. Moreover, I was a Canadian. I then went to one of the RCMP officers, I wanted him to witness and sign his name to the form as well. I vowed to him that if the government wanted to expatriate me I wouldn’t go alive. The officer was sympathetic to my reasons.”

Aya stayed in Canada.

Life Improves For Aya, But The Internment Camp Lessons Remain

After the war, the British Columbia Security Commission closed down the Japanese school. The remaining Japanese children in Kaslo attended the local school, and Aya went to Slocan City for a year to teach in Slocan’s Japanese school.

Life improved. The Canada Act passed in 1947, proclaiming that anyone born in Canada was a Canadian citizen. April of 1949 brought the removal of restrictions placed upon Japanese-Canadians, now free to go anywhere in Canada. Aya, newly-married to Buck Higashi, was now a substitute teacher at the Kaslo school. The principal, Greg Dixon, encouraged her to get her teaching certificate. Yet despite this progress, the lessons of the internment camps remained. “Years of being called an enemy alien, and I thought that I would file my naturalization papers. Do you think I could actually get anyone to listen to me?”

Throughout the early 50s Aya sought naturalization with government agents in many communities across B.C. “Finally, in the mid-50s, when the new government agent Tom McKinnon came to town, I convinced him to proceed with the paperwork.” Aya finally received her naturalization papers. “Buck and I were fully prepared to move back to the coast but we soon realized how deep our roots were in the community and we couldn’t leave. This town’s kids were all my kids.”

The trials of Aya’s family are not unique. No other ethnic community in Canada was treated as unfairly as the Japanese during World War II. Kaslo and other former internment communities have not ignored the contributions of internees: Kaslo’s Langham Hotel is now the Langham Cultural Centre and houses the Langham Japanese Museum to commemorate Japanese-Canadians. These are testaments not just to a time of injustice, but to the legacy and patriotism of Canadians like Aya Higashi.