In Canada, we assume that the plight of garment factory workers is a third world dilemma. But in East Vancouver, one only has to open a back door for a glimpse of immigrant women sewing in a dingy, dimly lit shop. In many non-union shops, hours are long and pay is poor. Minimum wage is often ignored and workers commonly make three or four dollars an hour, depending on how fast they work.

In the boardroom of UNITE (Union of Needle, Industrial and Textile Employees), Vas Gunaratna sighs loudly, placing his hands behind his head. He says, “I don’t think the situation here is much different from what’s happening globally. Certainly, there is good and bad, but the same conditions exist now as did 50 years ago.” Gunaratna has been a union manager for nearly half that time. He is in charge of the biweekly inspection of 30 shops that manufacture fabric goods from draperies to gloves.

Occupational Hazards

UNITE traces its inception to the Triangle Fire in New York City, in March 1911. The infamous blaze ravaged the 10-story Triangle Shirtwaist factory, killing nearly 150 employees, mostly young immigrant women.

Bodies, dead or barely alive, were heaped on the sidewalk for hours while firemen desperately tried to save the building. The event initiated direct action to protect garment factory workers from safety and health hazards, and employer exploitation. UNITE has been in Vancouver since 1947 and has existed in the US for over 90 years.

The workers represented by UNITE are primarily first generation Chinese immigrants and most speak little, if any, English. Though their work is difficult and boring, their benefits and holidays might make even civil servants jealous. Cultural events such as Chinese New Year are treated as statutory holidays and ESL classes are provided free of charge to workers.

Things couldn’t be more different in the non-union sector. Since NAFTA, the Canadian garment industry has seen many jobs go offshore, where labour is cheaper.

Lower Funding, Higher Risks

Because of the Liberal government’s cutbacks, Employment Standards’ funding is dwindling, and with it the board’s capacity to handle Vancouver’s garment industry labour crisis. Gunaratna says government information on labour codes is not provided to new immigrant workers. The relevant documents are printed in English and are ultimately useless to workers who cannot speak the language. Even language training in the union sector is on its way out, due to funding cuts. Providing translated information packages to companies whose employees are primarily new immigrants would certainly be a step in the right direction. If labourers are aware of what they are entitled to, they may be disinclined to work for less.

Through a translator, Dola Zhou indicated she knew little about her rights as a worker when she started her first job in Canada at an East Vancouver garment factory. She says she was told that her job as a pieceworker didn’t entitle her to minimum wage. Gunaratna says it is a common practice for sweatshops to take advantage of employees who are unfamiliar with labour laws. According to the BC Labour Code, garment industry piecework is not exempt from minimum wage.

As local contractors slash prices in order to compete with overseas companies, they also increase piecework quotas to make up the difference. Ultimately, workers have to work faster and harder to take home the same money as before, and develop repetitive strain injuries faster than you can say globalization. Injured workers who can’t make their quotas are often pressured to resign, or are fired.

Tough Competition

Sometimes even when a company skimps on wages, it still fails to fend off the ravages of global competition. One such company, Eminent Knitting Ltd., ceased operations in December.

On March 23, several garment workers from the company asked UNITE for help. They claimed that their wages had been withheld since the previous November.

Eminent Knitting had employed close to 70 workers, mostly new immigrants. According to Zhou, who worked there just before the closure, company president Eddie Mak requested in November that employees not cash their pay cheques until the following month. The workers acceded. She says that in December, the request was made again. On Dec. 15, Eminent Knitting closed its doors. Most of Eminent’s employees were laid off. The workers told Pacific Rim Magazine they approached Mak again in February for their wages and were told he was going to China to get the money. Uncomfortable with their employer leaving the country, they turned to SUCCESS, a non-profit organization set up by the Chinese community to provide services, including legal counselling to new immigrants. The workers say SUCCESS told them Eminent Knitting had no assets and that nothing could be done to get their wages back.

Gunaratna said UNITE can’t do much for these workers since at the time of Eminent Knitting’s closure, they were not represented by a union.

Pacific Rim Magazine was unable to reach owner Eddie Mak to get his comments on the situation. Eminent Knitting has had problems in the past. When workers filed their year 2000 taxes, they learned that none of their taxes had been paid by the company. Mak paid the income taxes as recorded on their cheque stubs back to them in installments over the course of the year.

Wage Discrepancies

The outstanding wages prompted an investigation by British Columbia Employment Standards. Based on its assessment, even if the owner of the company is held personally responsible for the wages, it could take up to a year for the women to get paid.

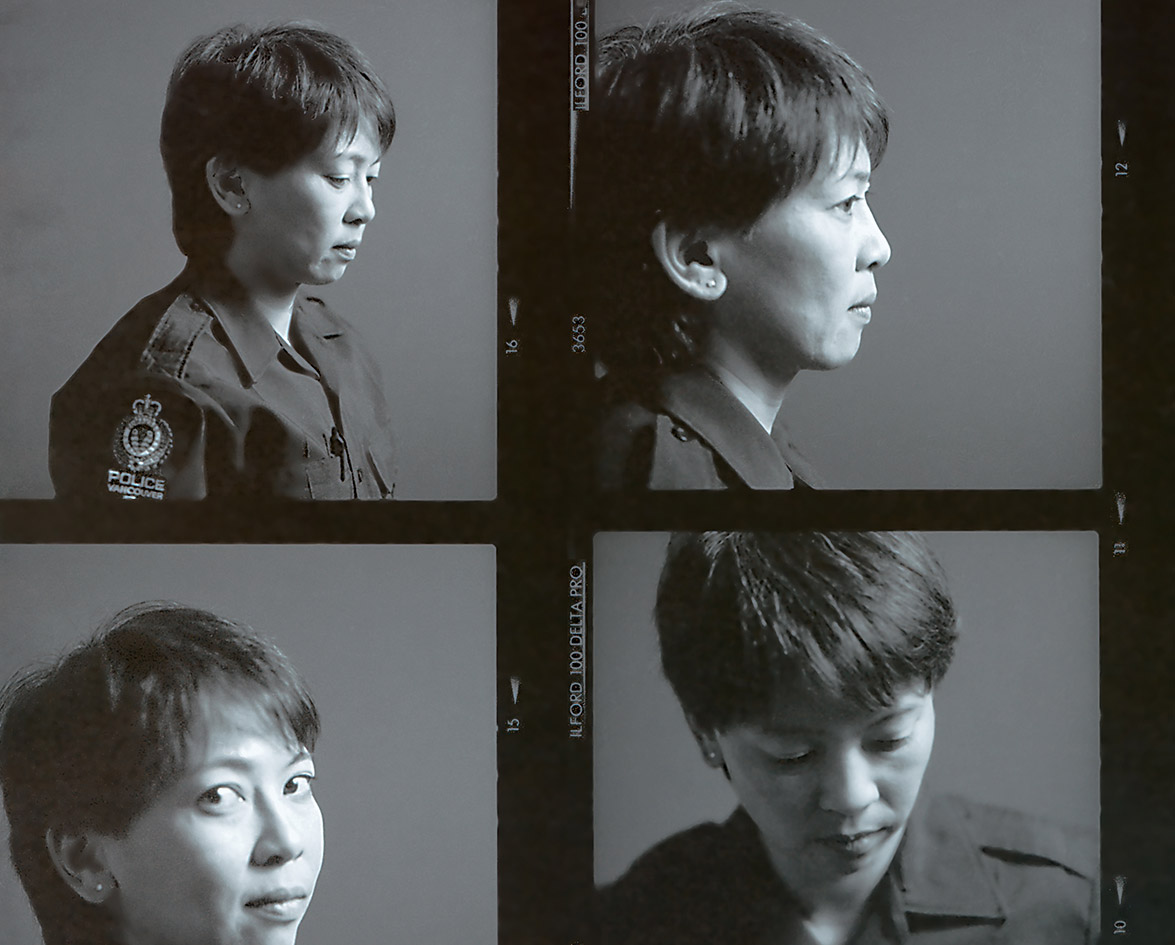

On the Monday following the workers’ complaint to the union, the court ordered a liquidation of Eminent Knitting’s assets. Everything from machinery and office furniture to the building itself was on the block. That afternoon, employees met with Gunaratna and UNITE secretary and translator Anita Yan in a rush to complete claims before the company’s assets were disbursed.

Other such Vancouver garment factories remain in business. Gradually, consumers are learning about the precarious position of many textile workers, but labour exploitation is still a confusing problem.

Exposing Corporations

The Internet is rife with information on brands that exploit cheap labour. According to workers’ advocates, boycotting individual brands often makes the workers’ plight more desperate. Even when boycotts are on a scale large enough to affect a brand’s profits, companies often respond with public relations campaigns, instead of actual change. Gunaratna says it is impossible to distinguish between union and sweatshop-made clothing. Some non-union shops are managed by good employers; they are not the ones to punish. Similarly, not all unions are effective. Some lack the organizational strength to pressure management for improvements.

Many workers’ advocates claim that labelling is a key to improving the situation of sweatshop workers. Employers in the union sector are willing to, and in most cases already do, label their garments as

Sweatshops take advantage of employees who are unfamiliar with labour laws.

union-made and identify the country of origin. But many brands don’t want to tell consumers where and how their clothing is made, citing the possibility that their competition will use the information to get the same great deal on cheap labour. Big brands frequently contract for labour through brokers who choose the cheapest manufacturer. The brands can then claim ignorance about what goes on in the manufacturing of their clothes, denying responsibility when the clothing they sell is manufactured in sweatshops.

It is largely the invisibility of manufacturing that enables sweatshops to exist. Sweatshops go out of business and new ones pop up. When consumers buy a product, the label may say Made in China, Made in the Philippines, or Made in Canada, but not always. Nor does the label identify the name and location of the manufacturer. If buyers knew exactly what conditions their clothes were made under, most would be more careful in selecting what they wear.