With the soft, agile fingers of her right hand, she caresses and plucks the strings stretching across the top of the instrument. The strings, at least 20 of them, are each held up by a bridge. Below the bridge, her left hand stretches, firmly gripping and bending the strings and the pitch. The harsh sounds tremble and ache. The blur of her racing fingers creates lightly falling rain, then a storm of sound, and finally a sweep into the twilight.

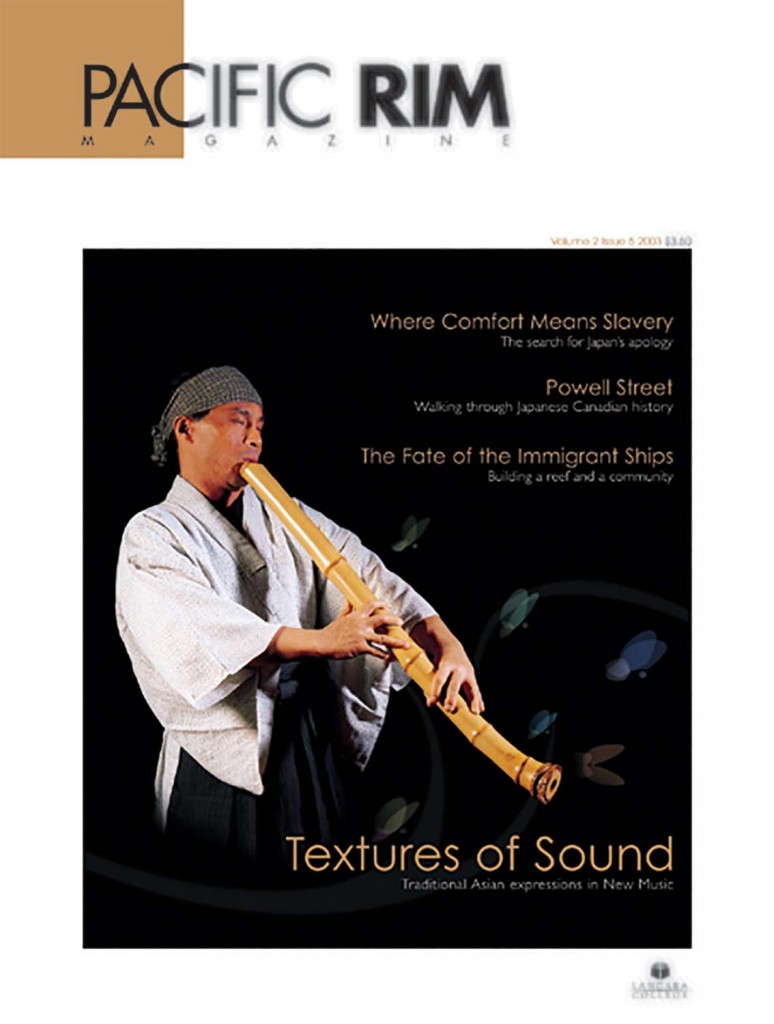

He holds a different musical instrument. It is a large piece of bamboo. His face is intense and shaking, blowing out vibrations. His fingers meld and flutter. Reflections of the many voices of nature sound out—frayed and gusty winds, sweet and breathy whispers, penetrating shrills and drones.

Intercultural Music Creates New Music

Vancouver’s strong ties to the Pacific Rim produce a local music scene rich with international music. Mei Han and Alcvin Ramos are two intercultural musicians who create innovative personal compositions influenced by their extensive knowledge of traditional Asian music. They count themselves among a field of artists who create New Music—a contemporary mix of musical styles and traditions.

These New Music experimentalists, like the Avant Garde musicians before them, take music to the next level—a divergent path that challenges and rewards the Western ear with deep expression and subtle nuance.

Interpreting Music

Traditional kinds of music in China and Japan have existed for over 2,000 years. Interpretation of this music depends on the performer’s personal experience and understanding of the traditions. Mei Han, an authority on the zheng (or “Chinese long zither”) and performer of traditional Chinese and contemporary music, has trained since the age of ten and received her first Master’s degree from the Musical Research Institute at the Chinese Arts Academy in Beijing. Han explained that, in China, a conservatory-trained musician has to know Western music theory. “It’s very ironic,” she said. “Most Chinese musicians don’t know Chinese music. They know better about Western music.”

Han’s two Master’s degrees in Ethnomusicology benefit her work, helping her feel more grounded and rooted in traditional music. “It’s very funny,” laughed Han. “Although I’d say I was a traditional performer, my expression of traditional pieces was shallow. But now, it’s deep. I’m trying to go even deeper.”

For Alcvin Ramos, playing his shaku-hachi, or “Japanese bamboo flute,” which is best appreciated as a solo instrument, is a spiritual practice. “The way you learn traditional shakuhachi is so different from the way you learn Western music,” stressed Ramos. “To understand it deeply, you have to go into the culture.” Before Ramos performs a piece, he describes its historic and poetic background to help people grasp the music.

Ramos studied only traditional Japanese music but was raised in contemporary Western culture. He believes that in order to appreciate music from different cultures, it helps to recognize that each culture listens to sound in unique ways. The shakuhachi makes use of many notes that do not fall within the pentatonic tuning of Western music. John Oliver, new music composer and performer, noted in an e-mail that, in working with Tokyo musicians Kazuhisa Uchihashi and Yahuhiro Otani, he found they shared a common desire to create quieter listening space in the music. Traditional Japanese music aesthetics express natural sounds and space not usually heard in Western music. To the Chinese, sound and music have a relationship with expression in poetry and philosophy. Each note has its own life and meaning expressed in different tones. The tonal colours, in contrast to Western music, denote the relationship between sound, silence, and nature. It is a spiritual relationship corresponding with other Asian music traditions.

Traditional Asian Music Discovered By Local Musicians

Westerners are becoming more interested in traditional Asian music as they hear its parallel with contemporary music. Many contemporary musicians from diverse cultural backgrounds have also discovered the beauty and elaborate expression of traditional instruments. Jazz great John Coltrane travelled to Japan to learn how to play the shakuhachi and deepen the spiritual quality of his music. Minimalist composer John Cage also visited Japan, inspiring the completely silent piece “4 minutes and 33 seconds.” He was known to use the Chinese I Ching in his music, art, and daily life.

Local musicians like Mei Han similarly find riches in Asian traditional forms. Before Han came to Canada, she was a strict traditionalist, unfamiliar with the concept of New Music. Today, Han is an accomplished improvisational artist, exploring new directions for the zheng and combining traditional with contemporary work that shares the common ground of freedom and expression. “The theory of the 2000-year-old Chinese music clearly states, again and again, about this musical expression—it should be free,” emphasized Han. “The breath of music is the breath of nature, the breath of air.” This same freedom guides New Music.

Each note has its own life and meaning expressed in different tones.

Han collaborated with Randy Raine-Reusch, an improvisational composer and artist specializing in world instruments, to release the album Distant Wind. Together, they try to create new works that maintain the spirit and aesthetics of traditional Chinese music. Another gratifying aspect Han finds in New Music is creating new sounds from the zheng by using anything she can get her hands on to make the sounds she wants.

New Music Provides A Diverse Sound

New Music breaks with classical Western compositions, going against what we perceive music to be while following the path of traditional Asian music. Ramos believes when you take different forms of music from diverse cultures and mix them together, innovative New Music is created. Similarly, for Oliver, “One of the most exciting aspects of working interculturally is bringing together the collective memory of the musicians and seeing how new music can be forged.”

Intercultural New Music thrives in progressive and culturally diverse communities. When living in China, Han had a limited view and knowledge of music. Now living in Vancouver, Han has expanded her musical range. Ramos, on the other hand, grew up in a multicultural environment, allowing him to find new ways of expressing himself. “Different and interesting things are happening here for me,” said Ramos, “like mixing with the Indian sitar or with Korean players. I probably wouldn’t have as much opportunity for intercultural mixing if I was living in Japan.”

Han’s performance at Vancouver’s New Music Festival this past October was significant. She performed three new works, one of her most challenging projects to date, and felt proud of breaking new ground by not repeating the repertoire people have played for generations before her. For Han, this is the importance of having your own voice. “I can find freedom in traditional music now, but I couldn’t before,” Han explained. “When I go back to reinterpret traditional music, I find the freedom. This freedom is what I get from playing contemporary music.”