In 1914, the Japanese fighting art of jiu-jitsu was brought to South America, where it began to undergo substantial changes and a meteoric rise in local popularity. Over the past century, one visionary family, the Gracies, has become synonymous with the sport by spearheading its evolution. The Gracie influence has had such an effect that Brazilian jiu-jitsu and Gracie jiu-jitsu have become interchangeable terms. Today, Brazilian jiu-jitsu has come to be regarded by many worldwide as the essential martial art, both for self-defense and for sport.

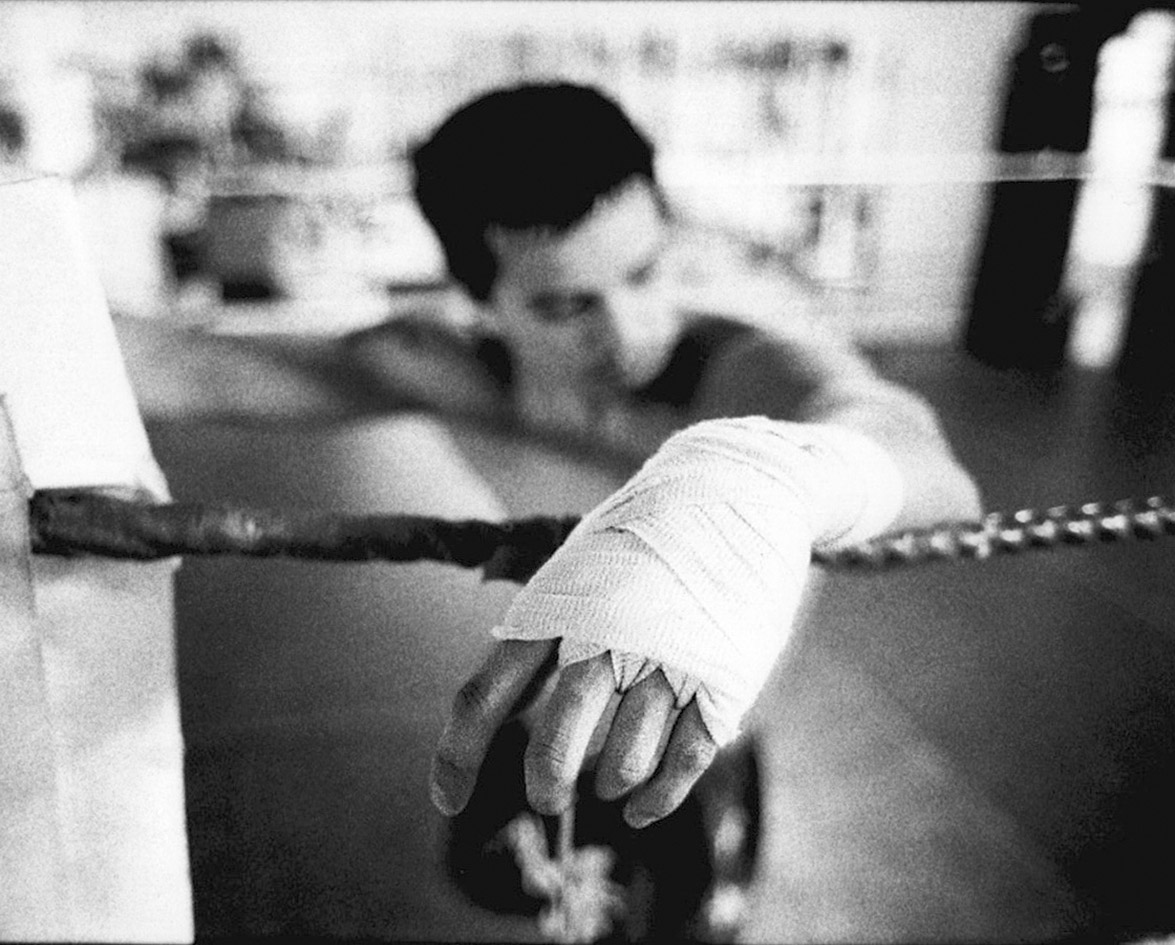

Since the early nineties, the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) has brought this fighting style to the world’s attention. The no-holds-barred, mixed style tournament brings together boxers, kickboxers, Muay Thai fighters, wrestlers and anyone else willing to put their skills, reputation and well being on the line. Time after time, Brazilian jiu-jitsu has proven to be the ideal mixture of techniques because of its fluid, strategic and cerebral approach.

The Metamorphosis Of Jiu-Jitsu

Jiu-jitsu’s long metamorphosis began in 1914 in Para, Brazil, with a Japanese immigrant named Mitsuyo Maeda. Maeda, convinced that the Amazon region was a better choice for Japanese immigrants than the United States, was working to build a Japanese community in the area. He worked closely with the Japanese and Brazilian governments to promote this idea. Maeda, also known by his fighting alias Count Koma, had been a renowned prizefighter both in Asia and in Europe before travelling to the Americas. Perhaps foreshadowing things to come, it is rumored that in Japan, he was expelled from the renowned Kodokan Judo Acaademy in Tokyo for participating in matches against fighters from other disciplines.

In Brazil, Maeda befriended Gastao Gracie, a local politician. Gastao offered to help Maeda promote and facilitate Japanese immigration in exchange for training his son Carlos Gracie. At the time, it was against Japanese law for jiu-jitsu to be taught to foreigners because of its original application as a hand-to-hand combat method, first for samurai, and later for the Japanese military. After training Carlos for almost ten years, Maeda returned to Japan, leaving essential knowledge in the hands of his student.

Carlos went on to open his own school in Rio de Janeiro in 1925. Around that time, Carlos’ father fell ill and Carlos took his brother Helio Gracie, 11 years his junior, in to live with him. Helio, the youngest of the family, was notoriously fragile as a boy. His parents never allowed him to engage in physical activity, fearing that his slight frame couldn’t handle it. Nonetheless, he watched his older brother teach classes until he had the moves memorized.

Fine-tuning Jiu-Jitsu

Legend has it that one day Carlos didn’t show up to teach and Helio offered to take over. He realized that he knew all the techniques, but found them difficult to execute with his diminutive stature. He began adapting the traditional jiu-jitsu to his own frail body’s abilities, fine-tuning the use of leverage in many of them. This is considered the turning point where jiu-jitsu in Brazil broke off from the original Japanese form, which was bound by tradition and rigid methodology. The two brothers went on to adapt the fighting style to better suit their needs, applying changes to the sport that would have been inconceivable under the strict Japanese guidelines.

Carlos’ son, Rolls Gracie, continued to expand the sport in the 1970s when he began training with wrestlers from the US and adapting wrestling techniques into their still nascent form of jiu-jitsu. Rolls is also credited with incorporating elements of the Russian fighting art, sambo, into the mixture. It is this openness to the mixing and sampling of different styles that makes Brazilian jiu-jitsu such a powerful force in events like the UFC and other vale tudo (anything goes) competitions.

The UFC was the brainchild of Helios’ son Rorion Gracie and was dominated by his other son, Royce Gracie. This first UFC was broadcast in 1993 on pay-per-view to an astonishing 86,000 viewers. By the fifth show, the number of viewers had increased to over 300,000.

The scope and spectacle of the UFC was definitely a new innovation, but not an entirely novel idea. The pitting of this martial art against others has been a fundamental element in its development. As far back as the 1920s, the Gracies were challenging fighters from other disciplines to highly publicized vale tudo matches, mostly to spread the word about their school and their new style. Helio’s first public fight at age 17 was against Antonio Portugal, the Brazilian lightweight boxing champion. Helio dodged one punch, took Portugal down to the floor, and won the match in less than 30 seconds. In 1950, Helio put forth a challenge to legendary American boxer Joe Louis to fight for a one million Brazilian cruzeiro purse. The fight never transpired. Throughout their careers, however, the Gracies continually challenged fighters from other disciplines, winning publicity and putting their methods to the test.

A New Breed Of Fighters

The vale tudo style tournament has created a new breed of fighters. Trevor Clarkson, director of the Creative Fighters Guild in Richmond, BC, explains: “It used to be that some guys would cross-train a little bit but mostly stick to just one style or just one art, convinced that it was the best. But as more people started seeing UFC, they started to realize that you have to cross-train. You need to mix up all these different elements to stay on top of what everyone else is doing.”

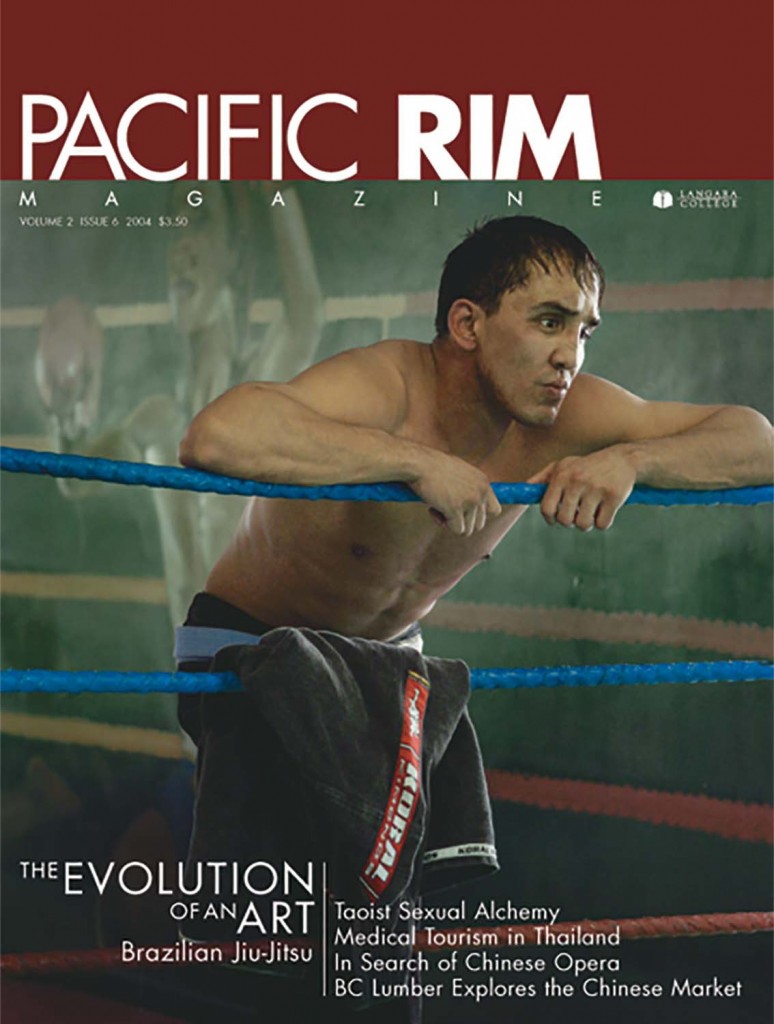

Dennis Kang is a Vancouver-based fighter who has trained and fought in many countries, including, Japan, Canada and the US. He has also trained with the Gracie family in Brazil. He agrees with Clarkson on the importance of cross training. “This sport is not just a jiu-jitsu match and it’s not just a kickboxing match. It’s a mixed martial art competition. So you’ve got to know how to grapple, you’ve got to know how to hit, you’ve got to know how to take the person down…Nowadays, cross-training is just training and training is cross-training.” Like countless others, Kang credits the UFC with sparking his initial interest in the sport more than ten years ago.

John Kefallonitis, who recently opened Universal Martial Arts in Vancouver, says: “A lot of people still mistake what you see in the UFC, the vale tudo, for Brazilian jiu-jitsu, but what they’re seeing is a mixture that happens when you’re applying it against other arts. But Brazilian jiu-jitsu is only jiu-jitsu; it’s just grappling…The vale tudo is what gets all the exposure from stuff like UFC, but I think real pure Brazilian jiu-jitsu is what’s actually more widely practiced as far as people who do it for themselves, or just for the love.” He also speculates as to why the art seemed to catch on so quickly. “Grappling is the most natural fighting art. From the time we’re very young we’re wrestling, rolling around. So when you do jiu-jitsu, it’s very easy for your body to pick it up— it’s based on natural movements. You don’t need any special skill because we all al-ready have those basic senses. It’s very natural for it to mix with other styles.”