On a sunny autumn day an eight-year-old boy yells, “Hey Jenny,” across the playing field at David Cameron Elementary in Victoria, B.C. The girl coldly walks by him. With a chill in her voice she says, “My name is not Jenny. My name is Jennifer.”

This was twenty-something years ago, and the girl was me. I have repeated that phrase throughout my life. Growing up in Canada, I thought the name my parents gave me defined who I was. My mother said my name was Jennifer, end of story.

In my early thirties, I enrolled at Langara College in Vancouver, B.C., where I met international students who had come to Canada not only for education, but to begin a new life. During my first week of classes, the instructors called out beautiful, exotic names, and to my surprise, many of the students said they wanted to be known by a western name. This fascinated me. It went against all my assumptions about the significance of one’s name. I have since learned that, although names are sometimes a connection to your cultural identity, they do not define who you are.

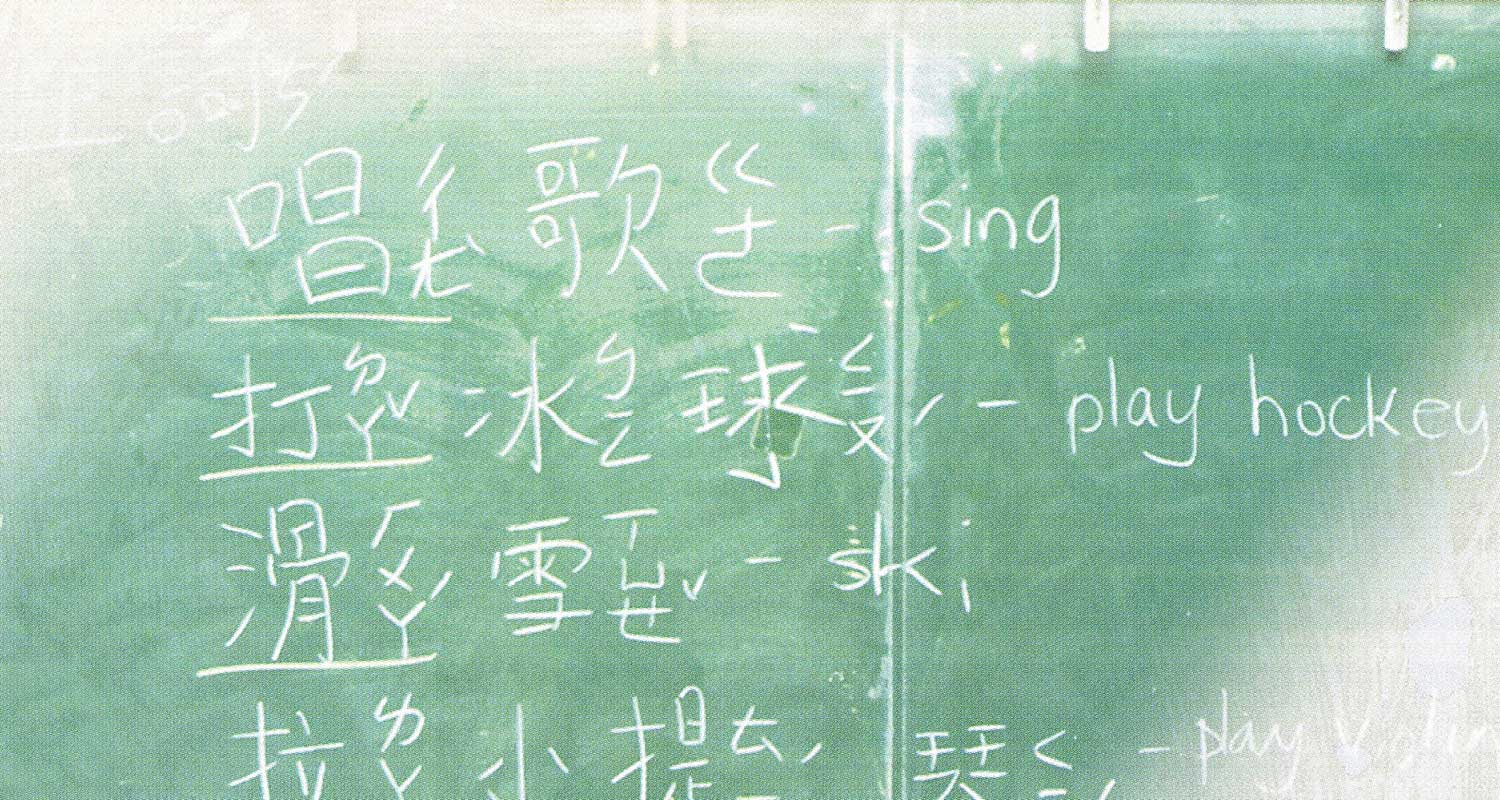

Jing ‘Jane’ Mu, a student from Tianjin, China, felt an English name would better acquaint her with Canadian society. When she arrived in Vancouver in 2003, her first Canadian friend gave her the name Jane because it sounded similar to Jing. She feels her English name will help her be accepted in Canada, and may help her in the future when looking for a job.

What’s In A Name?

When Yu-Li Chen was younger, her English-speaking aunt gave her the name Jennifer to use when she attended English school in Keelung, Taiwan. But Chen did not feel that it was a good name for her—it was too long and feminine for her tomboy ways. When Chen moved to Vancouver for school in 1998, she struggled with finding a Canadian name. Chen’s high school teacher told her to keep her given name until she found an English name that she liked. “I was trying to think of some English names at the beginning, but then I could not find one that I really liked, or that really represented me,” she says. After being in Canada for a year, Chen still considered finding an English name, but decided it was too much trouble. She liked how short and simple her name was, and everyone already knew her as Yu-Li. “I like my name. It represents me,” she says.

Margaret Lai Yuet Tan was born in Malaysia, but has lived in Canada most of her life. Her Cantonese parents gave her an English and Chinese name at birth. Tan feels her English name and her Chinese name, Lai Yuet, match in tone. At one time, she disliked having a Chinese middle name. “When you are a kid you are embarrassed about everything to do with your culture. When you get older you start to embrace it,” she says. Tan believes it’s unfortunate that people change their names to feel like they belong, when a name is such a big part of cultural identity. “Abandoning your Chinese name is almost like giving up your heritage,” Tan says. She is no longer embarrassed by her Chinese middle name and knows that if she has children, she will give them both English and Chinese names.

Shakespeare’s Juliet said it best: “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” Some people feel a strong connection to their given names, and others find a new connection with their chosen ones, but in the end it is who you are and not what you are called that counts.