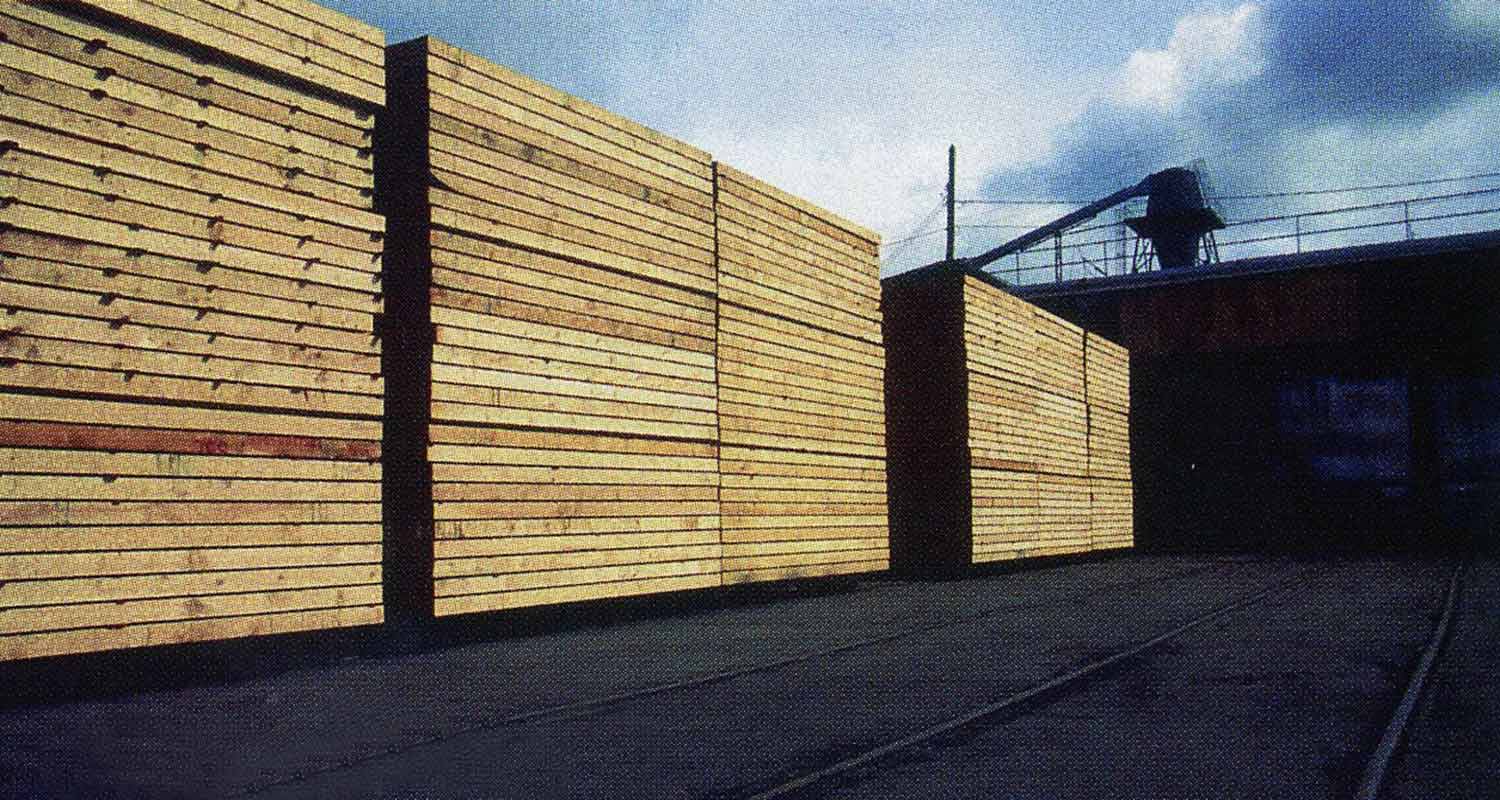

In 2001, the Softwood Lumber Agreement between Canada and the United States expired. The US, accusing Canada of unfair trade because of government-subsidized harvesting rates, imposed a 29 per cent tariff on all imports to the US exceeding 14.7 million board feet. Canada went to the North American Free Trade Agreement and the World Trade Organization to challenge the US decision. In March 2004 the WTO ruled in Canada’s favour, with NAFTA’s decision still to come. The ramifications of the rulings remain to be seen.

The US tariff caused great turmoil in communities throughout B.C. that rely heavily on the forestry sector. More than 20,000 jobs and ten billion dollars in trade have been lost since the SLA expired. Mills that have survived claim there is no profit in what little they can produce. Responding to this crisis, government and private industry have teamed up to open new export markets for lumber. China, with its increasing housing needs, is the primary focus.

Housing in China

Annual housing starts in the US are approximately two million. China is currently building ten million units, and that number is expected to reach 30 million by 2010. The US market has been an easy sell because, like Canada, wood-frame construction is the preferred method. Conversely, China builds nearly all its housing with concrete or masonry. The general perception in China is that wood is unsafe, not durable and too expensive. China also lacks a national building code for wood-frame housing and its workforce is untrained in wood-frame construction technology. Growing concern for China’s natural environment, combined with the efforts of Canadian agencies such as the Council of Forest Industries (COFI), is helping to change this, opening up new doors for wood-frame construction.

In recent years, many Chinese who have lived abroad have returned to China with positive reports of North American-style housing. Many successful entrepreneurs in China want to live the western-style dream, including owning villas in westernized model communities. Current estimates show five million people with an annual income over $200,000, many with a desire for western-style housing.

In response to high levels of energy consumption caused by economic growth, the Chinese government is striving to make China more environmentally friendly. This is evident in their ratification of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol agreement to reduce greenhouse gases. The central government is pushing for more energy efficient housing to help reduce these emissions. Wood-frames seem to be the solution.

Wood-frame vs. Cement

Wood-frame housing is a natural product that promotes a healthier environment and reduces energy consumption. A recent study by Toronto’s Gabor & Popper Architects shows wood, compared to concrete and steel, has the least impact on global warming and air toxicity. The Chinese Academy of Forests is also promoting wood-frame housing, because of its lower impact on the environment.

In addition to lower pollution levels, wood also outperforms concrete in seismic loading. This was proven in Kobe, Japan after the 1995 earthquake. Older buildings constructed with post and beam were leveled, while newer homes using wood-frame technology were virtually unaffected. The safety factor of wood-frame housing could prove to be critical if China were to suffer another disastrous earthquake like the one that hit Tangshan in 1976 and killed more than 250,000 people.

China is renowned for its construction of historic wooden structures like Beijing’s Summer Palace. These buildings have withstood hundreds of years of exposure to earthquakes, war and the elements. Over the years China has decimated its forests, creating a need for alternative construction methods. Concrete and brick have become the most common. At present, China’s 1.3 billion citizens possess a meager four per cent of the world’s forests. The Chinese Academy of Forests recently imposed a nationwide ban on harvesting the few remaining forests. Paul Newman, director of market access and trade at COFI, states, “[The yearly] shortfall in wood fibre is equal to the annual allowable cut in British Columbia.” This leaves a sizable gap between supply and demand that B.C. can help to fill.

The first Canadian-style wood-frame homes in China were constructed in the mid 1980s shortly after Deng Xiao Ping, China’s former leader, opened the doors to a market based economy. The agricultural sector was the first to prosper. Affluent farmers recognized the benefits of wood-frame housing and welcomed the Canadian product. Unfortunately, the 1989 events of Tiananmen Square brought most foreign trade, including the pilot projects, to an abrupt halt.

In 1999, Ron McDonald, then president of COFI, led a trade mission to China seeking new opportunities for wood product exports. Unfortunately, China did not have a building code that permitted the construction of wood-frame housing. Without the ability to build and sell, but only rent, developers were not interested in building.

New Building Codes In China

The same year, however, a memorandum of understanding was established between the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) and the Chinese Ministry of Construction. In January 2004, after four years of collaboration involving the efforts of many Canadian agencies, new building codes were passed in China with sections pertaining specifically to the use of wood-frame construction. Canadian lumber grading standards were approved. Currently, only Canada and the US are granted this status. This enables graded lumber to be used in legally marketed homes.

Forintek Canada Corporation, a non-governmental organization based at the University of British Columbia (UBC), had a key role in getting the revisions passed. Dr. Chun Ni, a wood engineering scientist at Forintek, was appointed as a full member of the Chinese Timber Structural Design Code Revision Committee with the Ministry of Construction in Beijing.

In November 2001, Canada and China formed three more memorandums of understanding to promote education and training for wood-frame construction. The first one, established between COFI, the British Columbia Institute of Technology (BCIT) and the Science and Technology Committee of the Shanghai Municipal Construction and Management Commission (STC), focused on a transfer of technology and vocational training. The second one involved the efforts of COFI, the City of Coquitlam and STC. The purpose of this memorandum was to train building officials. The third memorandum, between COFI, UBC, Forintek, the Canadian Wood Council, and Tongji University in Shanghai, focused on designer training and timber engineering research. Although these initiatives concentrated on activities in Shanghai, there was hope the success could translate into national industry standards.

Throughout China there are different nations involved in construction projects. Competitors, including Russia, New Zealand and the Scandinavian countries, do not yet have authorization to sell wood-frame housing. However, Dr. Ni claims this could change as a result of Canada’s success in revising China’s building codes. Still, Canada’s efforts in Shanghai could be key to a Canadian advantage. Shanghai has great influence over the rest of the nation and what becomes practice in this region generally spreads to other areas.

Until recently, Chinese consumers saw no distinction between a western-style villa constructed of concrete and a design using wood-frame construction. CMHC has been helping developers change the general Chinese perception of wood-frame housing. One strategy replaces the term R-2000 home (which is the Canadian standard of energy efficient housing), with the term Super-E home. Nellie Cheng, senior trade consultant with CMHC states, “Super-E signifies energy, efficiency, environmentally friendly, and economical.” As a result of these efforts, conscientious Chinese are becoming more aware of the benefits of living in healthier housing.

Sustainable harvesting of timber for wood-frame housing is necessary to the survival of many rural communities in B.C. The Chinese market has great potential, but certain conditions must be met, including sustaining the environmental and economic outlook for both trading partners. B.C. has strong ties with China and has formed a trustworthy trading relationship. Paul Newman believes “you’ve got a hard row to hoe if you’re just trying to sell the Chinese a product…to be really successful, you really have to look at it as, yes we’re going to gain something out of this, but you’re going to create jobs…and an industry [for China].”

Time is critical. B.C. needs to rebuild its forestry industry and China needs to build houses. Hasty harvesting without a concern for sustaining the resource, or haphazardly producing housing without addressing safety could produce undesirable results. Canada is not only looking for business, but wants to maintain fairness and integrity in trading practices.