In a small Korean village, two hours from the nearest city, Youngsin Lee’s parents joyfully anticipated the imminent birth of their first son. In a matter of hours, the whole village would celebrate the new gift from above–a baby boy to carry on the family name and ensure success in all family endeavors. Since the day they married, the Lees had hoped for a son. They were twice disappointed, bringing only daughters into the world. This time would be different, however. The townspeople, the midwife, and even the monks agreed that when the ordeal of delivery was over, there would be cause for celebration. Then the unimaginable happened. When Youngsin wriggled down the birth canal and entered the world with a wail, both midwife and mother could not believe their eyes. They held in their arms a baby girl–he was a she!

As a young girl in Korea, Youngsin didn’t fit the traditional definition of femininity. Today, she is a mother and sculptor in Vancouver, British Columbia. Inspired by her experiences as a woman in Korea and an immigrant to Canada, Youngsin challenges, through her sculptures, the stereotypes that define women in a male-dominated society. Her artwork was featured at Gallery Gachet in Vancouver during Asian Heritage month in May 2005.

The Differing Roles Of The Sexes

Throughout her childhood, Youngsin gained a sense of the inferior social status of women. From an early age, she learned the differing roles of the sexes. Speaking with a strong accent, occasionally struggling to find the words, she recalls: “When [my mom] was pregnant with me, everyone, the monks, and all the people around her told her ‘this is going to be a son.’ Every family was so happy; it was very exciting. But then I came out and I was not a boy. So I heard they put me up to die… if you put a baby this way, [motions with her palm down] they can’t breathe… they put me down like that and then I guess they came back and turned me over. They were just so disappointed.”

In relating this scenario, shocking to our Western sensibilities, Youngsin’s tone is not judgmental. In the cultural climate from which she came, her family’s reaction was not uncommon.

Although she was not told about her brush with death until she was a grown woman, Youngsin felt from the beginning that she did not fit in. Guided by her grandmother’s Asian philosophy books, she began to do things a little differently.

Being A Girl And Dressing Like A Boy

“I hated myself for being a girl and I wished to be a boy,” Youngsin says. “We have many Asian books that tell you what men should be like and what women should be like. I hated everything that women should do, and I followed everything that men should do. If it says men should not cry, okay then, I never cry. I became a strong character.” She recalls the memory with a chuckle.

Like Viola from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night , Youngsin donned male attire whenever possible. She relished parades and costume events where she could shed her girlish appearance and revel in the freedom of the Korean male. Of course, Youngsin is not alone in rebelling against stereotypical images of femininity. Historically, the cross-dressing woman is a pervasive image in literature and film, and contemporary references abound as well, including Gwyneth Paltrow’s character in Shakespeare In Love and Barbra Streisand’s Yentl. In fact, upon close examination, the ability of women to defy narrow definitions of gender has proven to be a powerful feminist tool. The belief, not without foundation, is that a woman disguised as a man is no longer limited to traditional female roles because she has removed biology from the picture. Tasks that are usually considered out of her league – even forbidden – are now within the realm of possibility. These stories usually beg the question: why are women prevented from engaging in any given activity in the first place? Whether it be acting, studying the Torah, or simply playing soccer in a pair of shorts, the idea that biology determines social roles continues to hold women back.

Sculpting The Strength Of A Woman

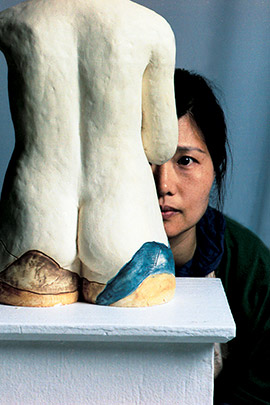

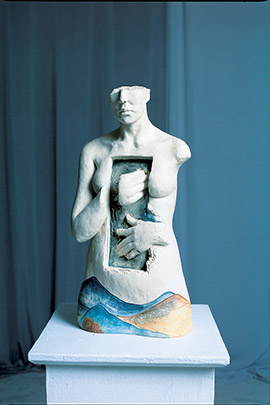

In reaction to classical and Renaissance pre-occupations with biology, the early-feminist movement in art prohibited representations of the female body because they were perceived as objects of male desire. Since the 1980s however, neo-feminist sculptors like Kiki Smith and Louise Bourgeois brought the female form back to the forefront. Using the female form, these artists explored alternatives to traditional stereotypes. Similarly, Youngsin’s sculptures use the human body to convey a message of female power independent from biology and male authority. Showcasing skills developed over years of formal training at Dongguk University in Korea, Youngsin’s sculptures are rendered realistically. The human form then becomes a canvas for artistic expression through etchings, carvings, and assorted additions. It is within these alterations that Youngsin’s artistic expression finds a home.

Challenging Stereotypes Of Femininity

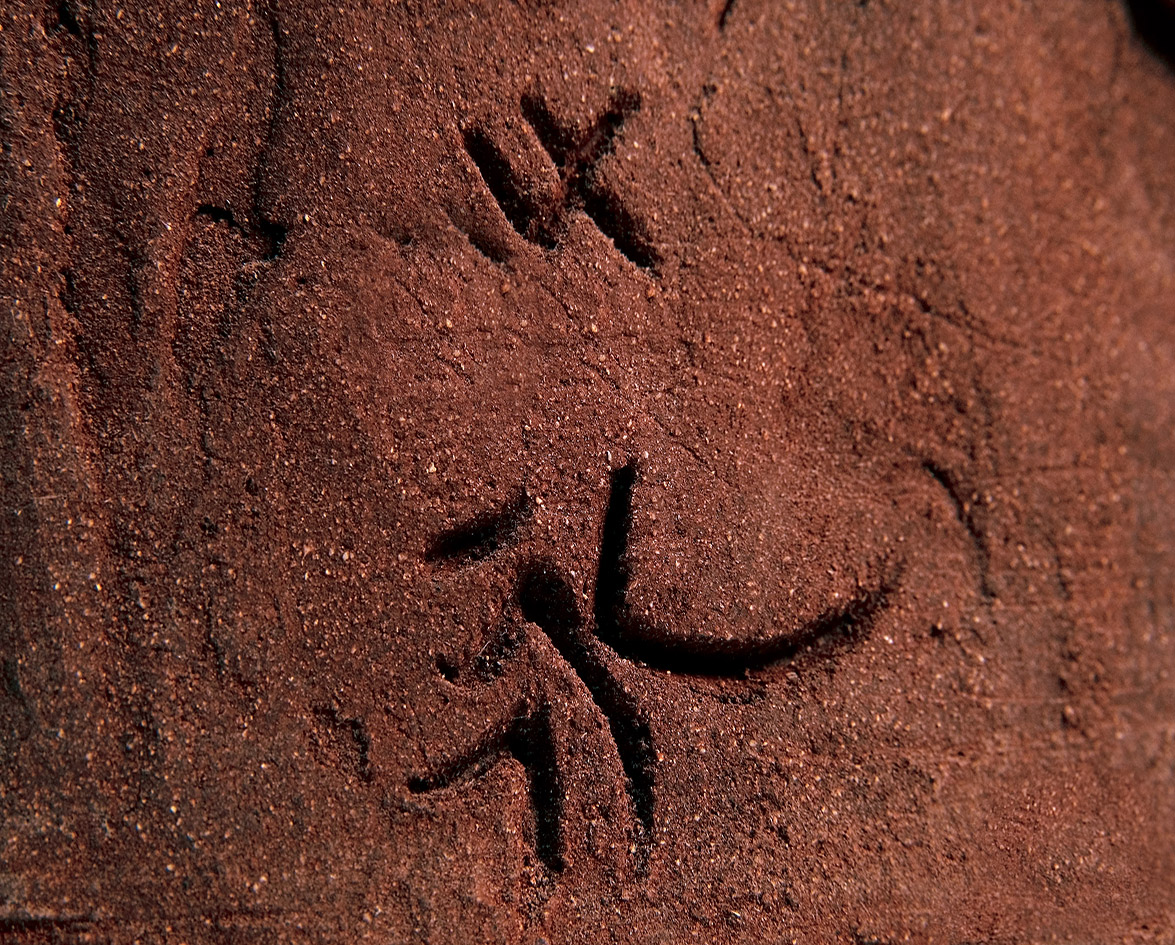

Her previous exhibit at Gallery Gachet, Strangers,featured a series of sculptures called The Value of Empty . These pieces included clay heads and obviously female torsos: all heads lacked hair. Patterns and Chinese characters were carved into the sculptures. Some had hollowed chests containing angular shapes, organic patterns, and in one case, another human form. Youngsin explained that an androgynous head, paired with an obviously female torso expressed her resistance to gender stereotypes.

As a young girl, Youngsin tried to escape pre-determined female roles by denying her own biology. When she reached adulthood and became undeniably female, she realized her childhood attempts to deny her gender were foolish. In short, she maintains the right to be seen as a person first and a woman second. “When I grew up and admitted that I was a girl, I decided that I don’t want to try to be girlish or mannish,” she says. “With my sculptures, people will look at the face and they may think of a man. Although the body has breasts, it brings the two together. I just wanted it to be a person.”

Her ongoing struggle with identity was somewhat alleviated by her immigration to Canada. Originally, she planned a move to Italy with a group of Korean art students. They were seduced by tales of classical European training and streets lined with clay banks waiting for the passionate sculptor to harvest. However, fears of an impending arranged marriage forced her to flee. When her uncle offered her a place to stay, she accepted his invitation.

When she arrived in Toronto, Youngsin was amazed and inspired by what she saw. “When I first came here and I saw the women, they were like huge trees – a lot of power, holding their heads up and walking with power. Big, strong, women.” In Canada, she found a place where her strong character was no longer a liability that placed her at odds with society. Female power became an ideal for her. As a result, Youngsin created stylized busts of women with flowing hair and interlacing tree branches carved into their chests. These pieces show women as powerful, and yet they are not realistically rendered, signifying the unattainable power of the women she saw that first day in Canada.

Making Unconventional Art

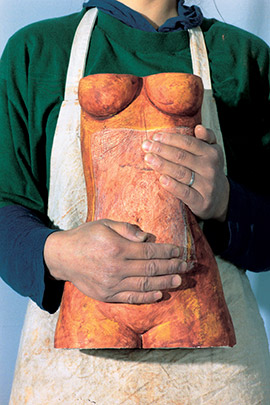

“Throughout her career, she has explored the human condition – most specifically that of foreigner and woman performing expected female roles as mother and emotional provider,” says Gallery Gachet coordinator Kirsten May. The series of pregnant torsos are headless and armless. Their only perceived value lies within pregnant bellies. An unconventional view of pregnancy, these pieces give voice to an aspect of the female experience rarely acknowledged: the alienation many women feel when pregnant, and as new mothers. However, they also signify a positive turn for the artist because, like her other series of voluptuous, headless torsos, their simplicity draws attention to the female body. “With these, I wanted to celebrate the beauty of women” Youngsin explains.

In her upcoming exhibit, To Be a Part of Our Story, Youngsin’s new optimism takes shape in more positive images of female power and freedom. Among her works in progress are clay busts of women with their chins held up and full heads of hair. The chests are cut away and replaced with tree branches more detailed and realistic than those incorporated into the stylized busts of her earlier works. The inclusion of male busts, a significant move for the artist, signals a more optimistic view of the power of the female gender.

“I don’t regret being a woman anymore; I want to be proud,” she says. “Some women seem to have a lot of power; I want to be more like those women. I’m still trying. I hope to get there before I die.”