According to numerous international surveys, the Japanese are the longest lived people on Earth. I have no doubt that’s true, since almost all of the Japanese members of my family lived well into their 90s. My great-grandmother, who was born in Yokohama in 1866, died only four years before I was born, and my grandmother, who died only recently, continued to live independently for 20 years following my grandfather’s passing. She was mentally razor sharp until the day she died at the age of 101. When I mention this to people, they look at me – that is, they study my blond hair and blue eyes courtesy of my Scandinavian father – and say “Yeah, OK …I think I can see it now. Maybe in the eyes….”

To get all the facts about my family history, I interviewed my grandmother one final time, only three weeks before she succumbed to cancer. Not surprisingly, as the story-teller in our family, she could recall every major event in her life – in our lives – in crystal-clear detail. She was able to recount so many events in the lives of her brothers and sisters – my great aunts and uncles – and the rest of our family. But there was one story that always stood out.

The Great Kanto Earthquake

“It was a Saturday, September 1st, 1923,” my grandmother recalled. “It was three minutes before noon, and I was at work, getting ready to leave for the day. My sister, Gertie, had just been to the dentist, and had come by the office, which was in the downtown area of Yokohama, in an area called the Settlement. I was just putting on my coat, and then it hit.”

What hit was one of the biggest earthquakes in modern history. By the time the Great Kanto Earthquake was over – in less than three minutes – 140,000 people had been killed, and the city of Yokohama had been wiped off the map.

“Gertie was standing in the doorway,” my grandmother continued. “It’s supposed to be the safest place to be in a building during a quake. Gertie shouted: ‘Come away from the fireplace!’ The shaking was so violent that the floor was moving from side to side, and up and down. I made my way to the door by holding onto a desk, and just as I reached the doorway, the fireplace, which was brick, collapsed onto the spot where I had just been standing.”

“The building where I worked was made of wood, so it was able to move with the swaying of the quake. But all of the brick buildings just shook apart. There were just a few people in the office that day – my boss and a few of the Japanese staff. Some piece of debris had fallen and hit me on my wrist, so I was bleeding. One of the Japanese clerks wrapped a handkerchief around my wrist, and then we started to leave the building. As we came out, we noticed a pile of bricks, and it started to move. We could see that a cart-horse was buried underneath, and was trying to stand up, but we couldn’t help; the city was starting to catch fire. I remember looking up at the building next door, which was occupied by a firm that exported silk. There were rolls of beautiful silk hanging out the windows, flapping in the wind like flags.

“There was a park a few blocks away, so one of our company managers suggested that would be the safest place, away from the fires that were starting up all around us. We made our way down to the street, and the whole city was in ruins. There were live electrical wires down in the middle of the street. We had to step over live wires, and we walked through puddles of water where live wires were. Of course, we had no idea what had happened to anyone else – to my mother, father, and my brothers and sisters: Charles, Emily, George and Maddie.

I noticed that there was a horse standing on the second floor. It must have run up the steps inside the building to get away from the fire.

“As we walked down the street, a man ran up to us, white as a sheet. ‘Can you help me?’ he said. ‘My family’s trapped.’ But we couldn’t help. Later, we passed a Japanese girl who was lying dead on the street. I could tell she was a telephone operator, because she was wearing a pleated skirt – a hakama – that was the uniform of telephone operators in those days.

“We saw the strangest things. A little further on, the front of one of the buildings had fallen into the street, so you could see inside the building. I noticed that there was a horse standing on the second floor. It must have run up the steps inside the building to get away from the fire.

“Gertie and I made our way to the park to get away from the fires. I began to sit down on a sheet of metal, and a man came over and said ‘Don’t sit there.’ I looked underneath the metal, and there were a number of dead bodies under it. There was a metal shop that had been nearby, and it had exploded, sending sheets of metal into the sky. One of the sheets landed on a group of people in the park, and had killed these people.

“The day had started out rainy, so I was wearing my oldest dress, because I didn’t want any of my nicer clothes to get wet. It occurred to me that all I had left was the dress I was wearing; and all of my nicer clothes – and everything else – were gone. We lost everything. My father had a huge library, including an original-edition first printing of Charles Dickens’ books. We weren’t even allowed to touch them, unless we were very careful. That all went up in flames.”

My grandmother recalled that she and her sister spent that afternoon and night in the park. There seemed to be no escape from the fires raging all around. Throughout the night, there were shakes – aftershocks from the quake. By the next morning, the fires had died down, and the people taking refuge in the park began to disperse, to search for family members and to see what was left of their homes.

“We tried to get to our house to see if any other family was there and if we could salvage anything,” my grandmother said. “At one point we rested, and someone we knew came along, and said: ‘It’s no use. There’s nothing there.’ Everything had gone. One thing I often think of: we had three or four budgies in a cage, and two canaries. The mother had laid an egg right in the cage, but it turned out to be a blind baby chick. They all burned to death.

“We decided to get down to a place called the Bund. It was a large plaza, and there was a road that ran along the seashore. The harbour was there, and a number of ships had been turned into rescue boats. At the eastern end of the Bluff, near the Grand Hotel, was a creek near the harbour. As we passed by, we noticed dead bodies in the water. People had likely jumped into the creek to escape the fires. There were dozens of bodies in there.

“George had found his way up to our house, and found our mother in the bamboo grove in the back yard. Bamboo is the best place in an earthquake, because the roots are so woven together. George helped my mother and her sister get down to the harbour. My father and Emily had found each other, and joined us.”

My grandmother recalled that the family began to assemble down at the waterfront. My great-grandfather, who was wearing a white linen suit, was covered with blood. When the quake hit, he was standing on the veranda of the foreigner’s club, looking through a telescope at one of the Canadian Pacific Princess ships. A friend of his was about to go on board, and my great-grandfather was wondering whether he should go down to the ship to see his friend off. When the quake hit, the wall gave way and one of the bricks came down and gashed his head.

We could see Yokohama from the ship. The whole city was on fire.

“My father and I were the only ones who were hurt,” my grandmother said. “Then we all got on one of the rescue ships – The Dongola. That night was quite a sight. We could see Yokohama from the ship. The whole city was on fire.”

“All our clothes were so filthy, and we had to wash them. People were walking around the deck with just sheets wrapped around them until their clothes were dry. There were crowds of people on the deck; no one had any private cabins or anything. The next day, the ship took us down to Kobe, where father had friends who put us up, and we had to start our lives all over.”

An Unconventional Family

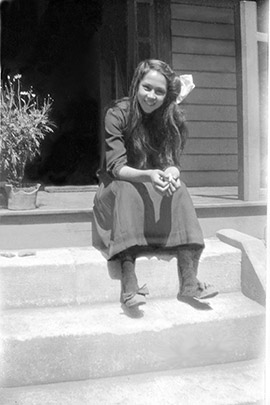

Our family’s history was filled with starts, and with starts-all-over. My great-grandfather, Eugene Fox, arrived in Japan from England in 1885 to open a branch of the family’s import-export business. Moving to Japan only 30 years after the country had opened to the West was a bold move, but there has always been a streak of unconventionality in my family. Even today, marriage between Japanese and foreigners isn’t all that common, but in the late 19th century, it was unheard of. My grandmother was always vague about how my great-grandparents got together. There weren’t many foreigners living in Japan at that time, she said, so for those looking to wed, the most likely choice would be to marry one of the locals. Interestingly, my great-grandfather spoke enough Japanese to get by, and my great-grandmother spoke virtually no English. Nevertheless, within a few years of his arrival in Japan, my great-grandfather married my great-grandmother, Taki Miyazawa, and together they had six children: Emily in 1890, Maddie in 1893, my grandmother, Lucie, in 1898, Charles in 1900, George in 1903, and Gertie in 1906.

Even today, marriage between Japanese and foreigners isn’t all that common, but in the late 19th century, it was unheard of.

My family lived in Yokohama, overlooking the harbour in an area the foreigners had named the Bluff. Due to the success of the family’s export business, the Fox family was well-to-do: they lived in a large house, entertained foreign dignitaries, and my grandmother and her sisters attended a convent school. Among upper-class families, women were expected to marry early, and certainly weren’t expected to work, particularly if the family was well off. My grandmother, who was fiercely independent, got a job immediately after high school, as did all her sisters.

Life before the quake was good, and my great-grandfather was typically Victorian in most ways. Everyone in the Victorian family was expected to be educated and cultured according to their social class, which meant that if you were in the middle or upper strata of society, you were expected to play a musical instrument or sing. And since electronic media didn’t exist, for entertainment, it was customary for everyone to gather round in the parlour for a family concert.

“Life was different in those days,” said my grandmother. There was very little in the way of radio or anything like that, so we would play music or take turns reading. Father was a good pianist. He wanted to send me to Paris to study music, but he couldn’t quite afford it. We would play piano duets together. George and Charles played saxophone, and Maddie had a lovely voice. There were times when we would get together and have a real concert. After dinner, in the evenings, we would take turns reading to each other.”

My great-grandfather would wear a suit in the style of the day, while my great-grandmother, in typical Japanese fashion, wore a kimono complete with an obi for formal occasions.

My grandmother recalled that one night in particular gave rise to laughter as the family read one of the popular best-sellers of the day – Dracula by Bram Stoker.

“Just as I was reading one of the most suspenseful passages of the novel, a light breeze entered through the open window, and blew the curtain behind me into the room, and I felt it brush against the back of my neck. I almost jumped out of my skin. Everyone laughed at that one.”

A Cultured Upbringing

Life in the Fox household was an eclectic mix of cultures. While my great-grandfather would read Victorian novels and organize family concerts, my great-grandmother, who was one of nine children, would entertain members of her family. And with both European and Japanese influences in the home, Regency and Revival furnishings mixed freely with classical Japanese lacquerware and cloisonné vases. When at work, and when dressing for dinner, my great-grandfather would wear a suit in the style of the day, while my great-grandmother always dressed in typical Japanese fashion – in a kimono, complete with an obi for more formal occasions. My grandmother and her sisters wore Edwardian styles until the 1920s, when the “flapper” look came into fashion.

Stories Of The Emperor’s

As I was growing up, both my grandmother and her sister, Emily, passed on to me all sorts of vivid recollections about life in Japan during the early years of the 20th century. Emily would relate stories of seeing the Emperor Meiji, who had abolished feudalism in 1867, and had re-invented Japan in the mold of a modern industrial state.

“I used to see him on his horse, always wearing his uniform and white gloves,” Emily would recall. “This would have been around 1895 or 1900. He used to attend horse races, and when he passed by, often on the way to the race track, people bowed and weren’t supposed to look directly at him, because the emperor was thought to be divine.”

One of the strangest stories was my family’s attendance at the funeral of Emperor Taisho in 1926.

“It was dusk, and there was a heavy fog,” my grandmother recalled, “The crowds lining the streets were absolutely silent. As the funeral procession passed by, you could hear the eerie sound of one wheel squeaking on the wagon that carried the emperor’s remains. The wheel was deliberately set to squeak as sort of a mournful cry, as the wagon was pulled through the streets. It was one of the spookiest things I ever witnessed.”

Setting Roots In Kobe

But being witness to historic events also meant being part of them, and after the earthquake – having to start life over, and having lost his beloved library filled with first-edition Victorian novels – my great-grandfather was never the same. He fell ill and died only two years later. By that time, my family had put down roots in Kobe, where they had been transported after the quake. In typically unconventional fashion, my grandmother and her sisters rented their own house, and were all working and independent.

In 1923, at the age of 22, my grandfather, Douglas Handford, arrived in Japan from England. Having apprenticed as a printer, he had secured a job as a reporter for an English-language newspaper in Kobe. My grandmother had joined the local hiker’s club where she met my grandfather, and a year later, my grandparents married in 1926. Soon after, my mother and uncle were born, and my grandfather took an executive position with Columbia Records. As a record executive, my grandfather had access to free studio time, and a number of recordings were made of my grandmother playing works by Beethoven. We still have those 78-rpm records today, and listen to them on occasion.

Life was comfortable throughout most of the 1920s, but family fortunes in the 1930s were a mix of good and bad. My grandmother’s older sister, Maddie was the first to marry, but she soon after died of cancer at the age of 30. (In fact, she was not in Yokohama at the time of the great earthquake; she learned of the quake while in hospital in England during her treatment for cancer.) Distraught, her husband drank himself to death shortly after.

Japan Becomes Hostile To Foreigners

Years later, more family hardships would follow. In 1938, while in Korea, my grandfather and uncle contracted typhoid. True to my grandmother’s indomitable spirit, she left the hospital one night at the height of the crisis, certain she would lose both her husband and her son, vowing to return to Japan with my mother to – once again – start over. My grandfather and uncle both recovered, but with the Japanese government in the grip of the militarist faction, local Japanese officials were making life increasingly difficult for foreigners and even those who were part Japanese. One consequence of the Japanese militarists’ anti-foreign views was that my grandfather was arrested and detained by Japanese police. At about the same time that local authorities began accusing my grandfather of being a spy, Japanese police stormed the family home, and discovered a map that my mother had copied from a Jack London novel. Things became truly absurd when police questioned my mother, who was 11 years old at the time, and insisted that her map was evidence of her involvement in espionage activity.

Leaving Japan In The Wake Of World War II

Finally, with the spread of World War II to the Pacific a virtual certainty, my grandparents, with my mother and uncle in tow, left Japan, arriving in Vancouver in November 1940. Having packed in a hurry, my grandparents were able to bring only a portion of the many items that had been part of their lives. While in Japan and Korea, my family had lived a life of comfort and affluence, with a full-time cook and even a chauffeur. Now in Vancouver, which was still in the grip of the Great Depression, they were faced with – once again – having to start over. With the Allied war effort gathering steam, my grandfather joined the navy as a lieutenant in the intelligence service. In 1942, he was sent overseas, and since he spoke Japanese, his main job was interrogating Japanese prisoners of war.

Needless to say, the war had split my family, and I lost family members on both sides of the conflict. In late 1941, my great uncle, George, and his wife, Dora, decided to get out of Japan. Even though war seemed inevitable, they made the fateful decision to remain in Hong Kong on their way to Australia. George was under the impression that the conflict would blow over quickly, and that he would get a job with the P&O Steamship line. The day after the attack on Pearl Harbour, the Japanese began their attack on Hong Kong. George left Dora to help out as an ambulance driver on the front line. He never returned. The Japanese defeated the British forces defending the city, and Dora was interned in a Japanese prison camp for the remainder of the war. Living on only a one bowl of rice a day for almost four years, she was determined to survive, hoping that she would be reunited with her beloved husband. When the war ended, she found that George had been killed during the invasion of the city in 1941. She was devastated, and spent a year in a sanitarium. Slowly, she recovered, and even returned to Japan, where she worked as an office secretary until she retired to Vancouver in 1966.

Starting Over In Canada

At war’s end, my grandfather returned from duty, and he and my grandmother travelled to Ottawa as language interpreters for the royal commission, which had been convened to return property seized when Japanese-Canadians had been interned. Soon after, my grandfather became a proofreader for the Vancouver Sun; my great uncle Charles returned from duty in the war, and joined an insurance firm.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the senior generation of my family passed away. Although she was the middle child, my grandmother outlived both her older and younger brothers and sisters, and everyone of her generation she ever knew. Nevertheless, she was determined to remain mentally keen. Even well into her 90s, she continued to live in the house she and my grandfather had bought in 1963, and continued to shop at the local supermarket, and get her hair done every week. And when the ambulance from St. Paul’s came to take her to the hospital one last time only two weeks before she died, she refused to allow the ambulance attendant to take her by the arm to help her.

“No thanks,” she said. “I’m going to leave this house on my own.” Always the independent-minded survivor – and after so many start-overs in her life – she was determined to do things her own way until the end. And mentally alert, even on the day before she died, when told that the woman sharing the ward had died the previous night from cancer, she said, “Hm, lucky thing.”

After my grandmother died, we finally began the task of opening the large steamer trunks that contained the household items my grandparents had brought with them to Canada. At my grandmother’s request, they had been left untouched for close to 60 years. In the trunks, we found a sterling silver tea service, hand crafted in the early 1920s. We found the small wreath that my grandmother had worn as a floral tiara at her wedding. I inherited a set of lacquerware made in the early 1920s and given to my grandparents as a wedding gift, still wrapped in newspaper that bore the date – May 14, 1940 – the time when my family had packed in preparation of their move to Canada.

At my grandmother’s funeral, I delivered the eulogy, and included some of the anecdotes in this article. In the eulogy, I mentioned that at age 101, my grandmother still remembered the name of her kindergarten teacher from 1903: Mrs. Kenderdine.

Our family still has many of the things my grandparents brought back with them from Japan, and we still use Japanese expressions in conversation. The legacy of our family’s Japanese heritage continues. I worked as an ESL teacher in Tokyo in the 1980s, and while there, visited the various sites in Yokohama mentioned in my grandmother’s stories: the church at Colonel’s Corner, the foreigners’ cemetery, and the area known as White Fence, where my family’s house stood before the Great Kanto Earthquake. I’m glad to be the inheritor of so many stories, but most of all, I’m glad that my grandmother, who died only three months short of living through three centuries of history, was able to pass on so much rich detail before her very final start-over as she left her house one last time before her final passing.