Sid Chow Tan is a patient man. The human rights activist and director of the Vancouver branch of the Chinese Canadian National Council has been involved with the head tax redress movement since it began 20 years ago. “I was a young man when this started,” he says with a laugh.

Since 1984, the CCNC has represented nearly 4,000 Chinese-Canadians in the fight for acknowledgement and compensation for the head tax imposed on Chinese immigrants between 1885 and 1923. The organization maintains that the tax and the Chinese Immigration Act, in place from 1923 to 1947, stunted the growth of the Chinese-Canadian community, caused decades of economic hardships, and tore families apart for almost 25 years.

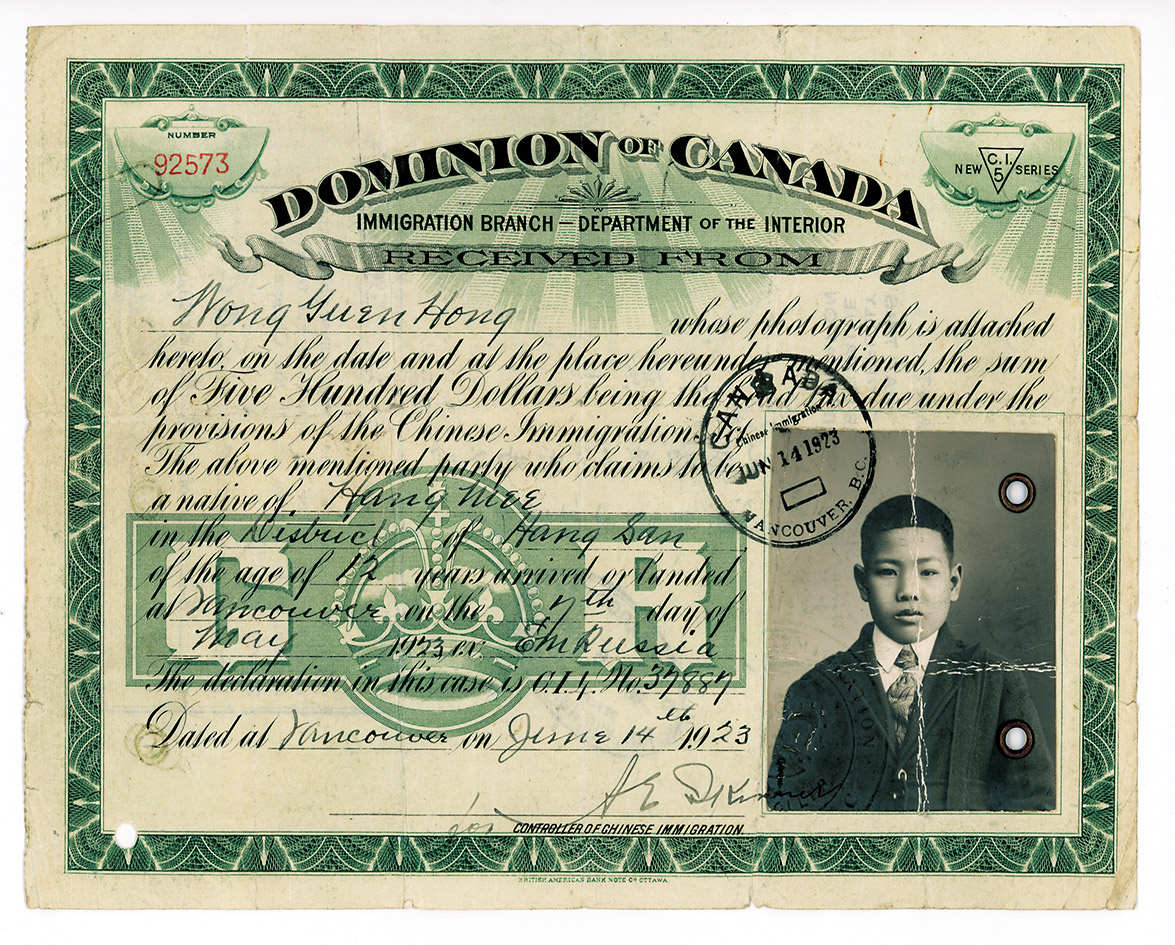

The Head Tax

For almost a quarter of a century, the Chinese-Canadian community has kept the head tax redress issue before the federal government. With the number of living head-tax payers having dwindled to just over two dozen, a second and third generation of Chinese-Canadians has taken the lead in a new campaign for recognition and justice.

Sid Tan’s grandfather, Chow Gim Tan, was a head-tax payer. He tended cows in China from the age of 10 to save enough money to come to Canada. Tan arrived in 1919 when he was 19 years old. Like many Chinese immigrants, he paid the $500 head tax. He settled in Saskatchewan and adopted the name Norman. He became a cook, opened a restaurant, and developed a love for hockey and cooking wild game.

The Lo Wah Kui Pioneers

Norman Tan was a lo wah kui , which translates as someone who is one of the old overseas Chinese from the poor and overcrowded southern provinces of Guangdong and Fuijian. He came to Canada in search of a better life. The lo wah kui were pioneers of the Chinese-Canadian community. And they were targets of the Immigration Act, also known as the Exclusion Act because the legislation prohibited Chinese immigration. No other ethnic groups were singled out. Tan was fortunate enough to emigrate to Canada before the act came into effect.

Chinese Immigrants And the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Chinese contribution to the building of Canada is without question. During the construction of Canadian Pacific Railway, approximately 17,000 Chinese immigrants arrived between 1881 and 1884 to work on railroad construction. “This was an immensely important project, and its completion would have been further delayed without Chinese labour,” says Hugh Johnston, a professor of Canadian history at Simon Fraser University. “They were, along with other ethnic nationalities, brought into Canada to build infrastructure.”

University of Saskatchewan sociologist Peter S. Li concurs. In his essay The Chinese Minority in Canada , he claims “the usefulness of Chinese labour in mining, railroad construction, land clearing, public works, market gardening, lumbering, salmon canning and domestic service was well recognized by many employers and witnesses who appeared before a royal commission in 1885 and 1902.”

After the railway’s completion in 1885, the federal government imposed a $50 fee on any Chinese immigrant entering the country. The head tax, as it became known, was the government’s response to concerns in the labour sector and middle and lower classes of British Columbia about the growth of the Chinese population. The head tax was raised in 1900 to $100, and then again to $500 in 1903.

The Chinese Immigration Act

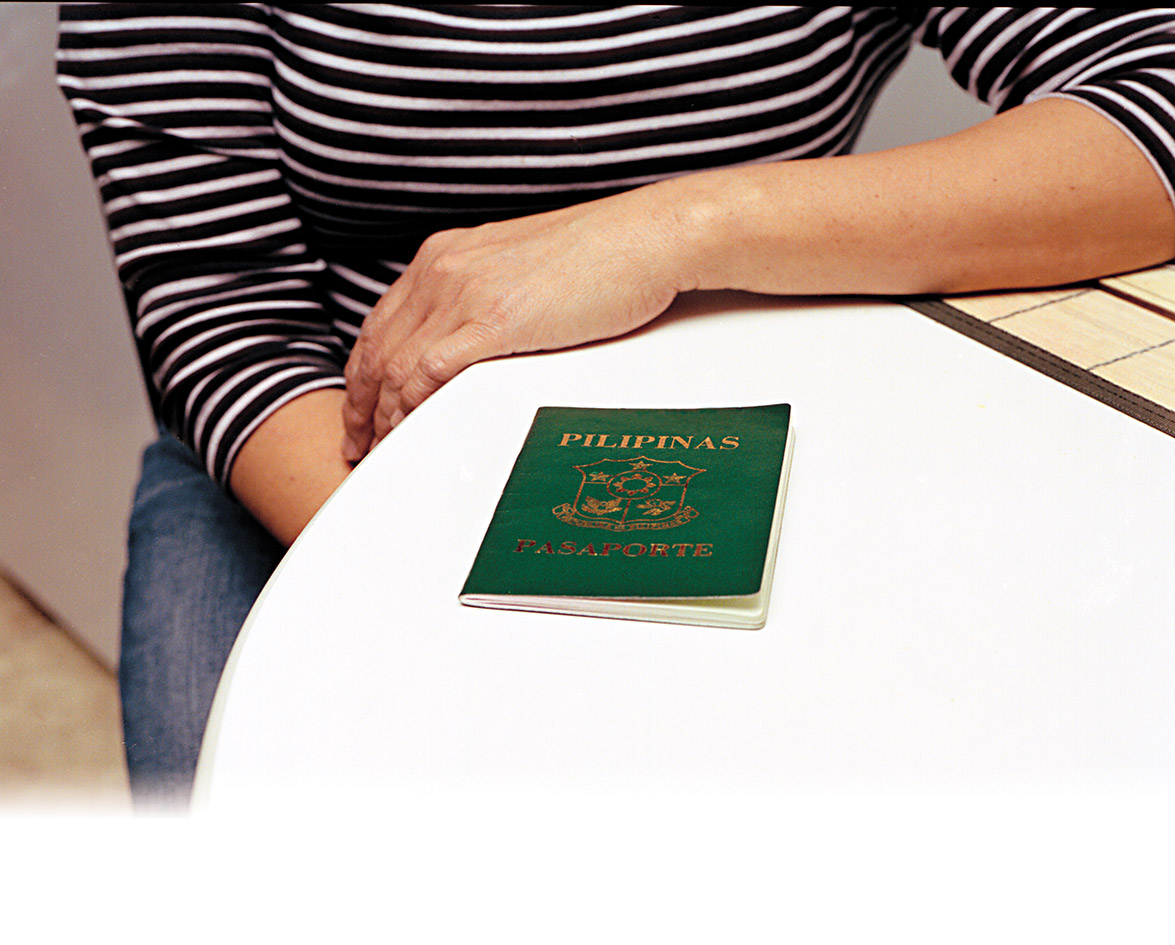

On July 1, 1923, the federal government passed the Chinese Immigration Act. For Chinese-Canadians, Dominion Day became known as Humiliation Day. Those who paid the head tax were allowed to stay. Many were men and boys with families in China. The Exclusion Act meant that they would be separated from their relatives for almost 30 years. Li claims, “The absence of wives and family also meant that the growth of a second generation was delayed.”

For Chinese-Canadians, Dominion Day became known as Humiliation Day.

Following the Second World War, in 1947, the federal government repealed the Chinese Immigration Act. Along with this restoration of citizenship, Canada opened its doors to Chinese immigrants once again, and many Chinese-Canadians were able to bring their families into the country.

Redressing The Head Tax

In 1983, Leon Mark presented his head tax receipt for $500 to his Member of Parliament in Vancouver. He asked her to help him get a refund. After the government refused to refund Mark’s money, the Chinese Canadian National Council took up the cause. By 1984, the CCNC had signed up approximately 4,000 head-tax payers, their spouses or children.

The 1988 settlement between the National Association of Japanese Canadians and the government over the internment of Japanese-Canadians during the Second World War showed promise for the Head Tax Redress movement. But in 1994 the government stopped negotiating, and rejected the idea of redress. Little progress was made until 2000.

In December 2000, a head-tax payee, a widow of a payee, and the son of another brought a class action suit against the federal government. According to the CCNC’s Redress Campaign website, the case claimed that the government was “unjustly enriched by the Chinese Head Tax that was in violation of international human rights that existed at the time.” The Ontario Superior Court dismissed the case in 2001. In his ruling, Justice Cummings commented that the redress issue was a political matter; it was not a matter for the judiciary. He recommended that the federal government seriously reconsider redressing issues raised by the head-tax payers, their widows and families.

The dismissal was not a setback, however. “We knew that it might not win,” said Sid Chow Tan. “But we got the recognition.”

The Ontario Court of Appeal dismissed an appeal in 2002. The Supreme Court of Canada also denied the council’s appeal in 2003.

The Last Spike Campaign

In September 2003 the CCNC began the Last Spike campaign, a cross-country tour to educate and mobilize communities to support the redress movement. Pierre Berton donated an actual railway spike found near Craigellachie B.C., the site of the historic Last Spike ceremony in 1884. Berton, a noted Canadian author who wrote the history of the building of the CPR, endorsed the campaign. In the press release for the Halifax kick-off ceremony, he wrote, “The last spike marked the end of a nation-building project in Canada. It also signified the beginning of a shameful era of the exclusion of Chinese immigrants. Let this new journey of the last spike bring about the rebuilding of our nation by redressing our past wrongs towards Chinese-Canadians.”

In April 2004, Doudou Diene, the United Nations special rapporteur on racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, and related intolerance, gave the redress campaign an added boost. He presented a report to the federal government that, according to Lynda Lin of the Pacific Citizen, recommended that the government consider making reparations on the head tax issue.

While the federal government maintains its no-compensation stance, there have been two private-member motions put forward in the House of Commons. Each favours different types of compensation. The CCNC prefers individual compensation. Another group, the National Congress of Chinese Canadians desires community compensation.

The National Congress Of Chinese Canadians

Manitoba Conservative MP Inky Mark introduced a private member bill in parliament on behalf of the National Congress of Chinese Canadians. Bill C-333 asks the federal government to negotiate with the NCCC to arrange for community compensation, rather than for individuals.

In a recent interview with Charlie Smith of the Georgia Straight, Mary-Woo Sims, former chair of the B.C. Human Rights Commission, criticized the bill for singling out the NCCC as the main representative of the Chinese-Canadian community. “I think if the government is serious about negotiating redress, whether it’s with Japanese-Canadians, or now with Chinese-Canadians, they ought to develop a process whereby the community identifies who the legitimate agents for that negotiation should be,” said Sims.

Vancouver East MP Libby Davies recently put forward another motion. Private Member Motion M-102 suggests that the government negotiate with the individuals affected by the head tax and Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 as well as with their families or representatives. The motion calls for parliamentary acknowledgement of the injustices of the legislation, an official apology by the government to the individuals and their families for suffering and hardship caused by the measure, individual compensation and a trust fund set up for educational purposes to ensure that such injustices can never occur again.

The Chinese Canadian National Council favours individual compensation, something that Bill C-333 eschews. “It stinks,” says Tan about Bill C-333. “Libby’s is a better way to go. If we get what Libby has, that would be fair.”

Too much bureaucratic debate, however, can stall any progress on this issue. When the redress movement started in 1984, the CCNC signed up over 4,000 claimants, including 2,000 head-tax payers. “There are probably only 20 to 30 left in Canada. Are they waiting for our people to die?” asks Tan.

A Fifth Generation Of Chinese-Canadian Creates Documentary

A fifth generation of Chinese-Canadians has recently taken up the cause. Karen Cho’s documentary In the Shadow of Gold Mountain premiered nationally in 2004. In the film, the 25-year-old Concordia graduate explores the disparity between the two sides of her heritage. While her British grandparents were welcomed with open arms, free land, and instant citizenship, Cho’s Chinese ancestors faced blatant discrimination. She set out to find others who shared similar backgrounds.

On her journey, Cho encounters a handful of characters, including three remaining head-tax payers, widows of payers and their children, and hears tales of incredible discrimination. In the film’s most moving moment, Gim Wong, an 82-year-old son of a head-tax payer, tearfully recounts a painful childhood memory of being chased and beaten by older white boys. Cho was overwhelmed by this story. In a phone interview from her Montreal office, she commented on the number of emotions that surfaced on her journey.

“When Gim was telling me that story, I sat there and cried.” She is also angered by the injustice of the head tax and the era of exclusion, especially as it impacted families. “Look at Charlie Quan and Mr. Wing,” she says, referring to two surviving head-tax payers who were featured in the film. “They were both separated from their wives for 30 years. In Chinese culture, everything is about the family.”

When asked about the implications of the film, Cho maintains that it is mainly about Canadian identity. She challenges the commonly held, Eurocentric approach to Canadian history. “This is a Canadian story and I think it is important to tell it that way,” she says.

Cho hopes her film will serve as a catalyst for social debate, and will renew interest in a chapter of Canadian history – one that is overlooked in most high school curriculums and college history courses. She also hopes to advance the redress cause. “The bottom line is that this is a human rights issue,” she said at the post-premiere question and answer period. “I think that when people of my generation hear of this, we are less forgiving. Younger generations will fight for this.”

The Chance Of Losing Impact

Undoubtedly, the movement will lose some of its impact when the last head-tax payer is gone, but Tan does not predict any loss of momentum. He views the current Canadians for Redress campaign as a success and its goals more attainable than ever with a minority government in power. “I think it is a winner,” he says. “There is more and more publicity. These things take time, but I think it may happen before the next election.”

“This is my grandfather’s story,” says Tan. “It is one of the darkest chapters of Canadian history, but also one of the brightest because they overcame the elements and the people. The lo wah kui are the ones who deserve the refund. They paid it, so they should get it back first.”