Field of Dreams. Major League. Bull Durham. Baseball has written itself into the collective consciousness of North America, and our movies, songs and literature reflect this obsession. It is not that often, however, that baseball has affected the actual lives and self-perception of an entire community.

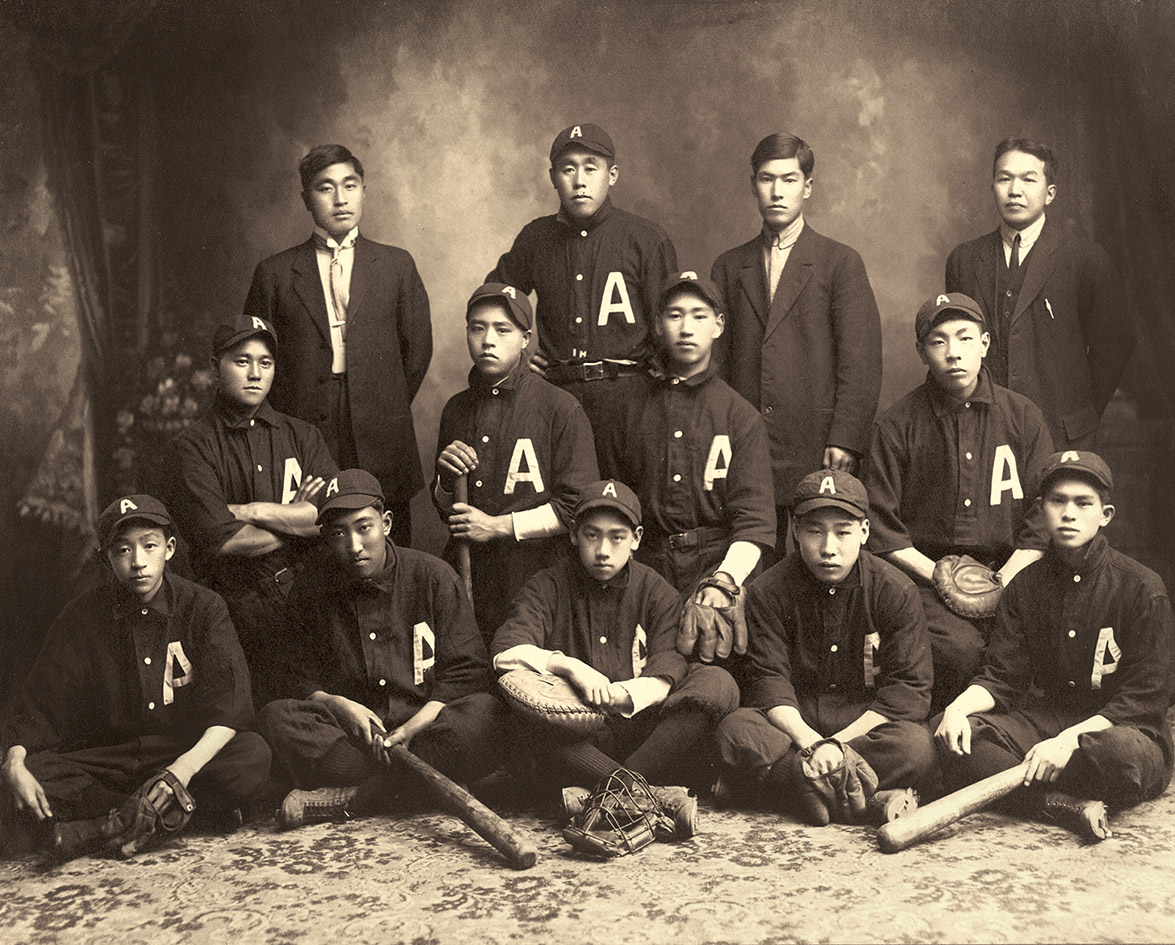

Before Jackie Robinson challenged professional baseball’s colour barrier in 1947, the Asahi Baseball team, made up of Japanese-Canadians, helped break racial barriers in Vancouver. They provided inspiration to a community that couldn’t vote, were barred from certain professions, and had two strikes against them even before they stepped up to the plate. As the only non-Caucasian team in their league, the Asahi faced racism and much larger opponents, but consistently proved their sportsmanship and skill.

The Asahi played baseball from 1914 to 1941, when the attack on Pearl Harbor led to the internment of Japanese-Canadians living along the coast of B.C. An exhibition at Nikkei Place honours the Asahi, their contribution to baseball, and the inspiration they provided to a community.

Nikkei Place is a Japanese-Canadian cultural centre in Burnaby, B.C. It was built in part with money from the Canadian government’s reparations fund for Japanese-Canadians interned during World War II and money donated by the community. Nikkei is a term that describes Japanese-Canadians, and everything about Nikkei Place’s design reflects the harmonious blending of the two influences. Outside, the garden is divided in half by a Japanese cedar. On one side of the garden the plants are native to British Columbia. On the other side, they are native to Japan. The plants climb a gentle slope and overlook an oval of grass, like bleachers at a stadium. Inside Nikkei Place, the elliptical atrium reflects the outside garden. Two giant pillars dominate the space, one of B.C. red cedar, and one of Hinoki, Japanese cypress. A diamond of tiles on the floor joins the two pillars, like two colossal runners poised at first and third base.

Exhibiting Asahi History

Tucked off to the right side of the atrium lies the Japanese Canadian National Museum, where the Asahi exhibit is housed. The first thing one sees upon entering the exhibit are vivid cut-outs of Victorian houses towering over a team of cardboard Asahi players. The exhibit, designed by D. Jensen and Associates, beautifully evokes early 20th century Vancouver and the area running along Powell Street, which was referred to as Japan Town. Japan Town, a self-contained community, was home to about 10,000 residents and was the place where the story of the Asahi began.

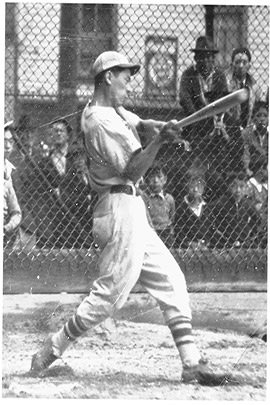

The exhibit presents this story through pictures, newspaper clippings and rare memorabilia, including a diminutive Asahi uniform, its original creamy white turned brown with age.

It was no surprise the Japanese community in Vancouver turned to baseball for recreation. Baseball had been taught in schools in Japan since the 1890s as a form of “moral discipline.” The Japanese language has no word for sport. Instead, it uses the term for martial arts to fulfill this function. The practice of martial arts is well-known for its reliance on the ideas of honour, dedication and perseverance. The Asahi used these ideas to triumph over larger, stronger opponents and racist umpires.

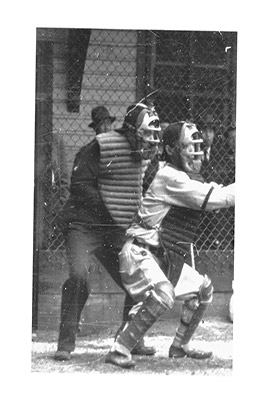

One of the directors of the exhibit is a charming man named George Oikawa. His white hair is tousled and his small, compact body bounces with energy. It is easy to see the baseball catcher he once was and the Asahi fan he still is. As he speaks of the Asahi’s achievements, his friend Elmer Morishita, who is also a director, listens in. A smile is on Elmer’s face and a bowl of popcorn is in his hand. George and Elmer have been watching baseball movies upstairs.

“After being taunted all day, they could go to the baseball field, where a strike was a strike.”

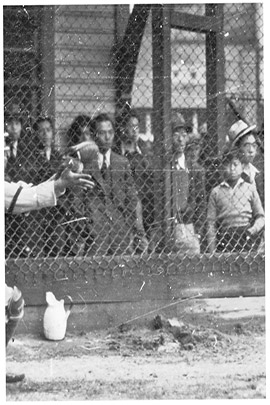

When George was a young boy living in Japan Town, he watched the Asahi play whenever he could. As he speaks of them, it is clear that the power of the Asahi went far beyond athletics. For the Japanese community, who lived along Powell Street for the first half of the 20th century, George says the Asahi, “meant everything. It inspired them. After being taunted all day, they could go to the baseball field, where a strike was a strike.”

The Asahi were exceptional athletes, and eventually they gained the attention of the Caucasian press. However, the articles written by the press still contained language that would be considered racist. One headline from the time read, “Japs and Grits in Contests. Little Brown Men and Young Liberals in Feature Battle Tomorrow” (The Vancouver Sun, 1926). The Asahi looked past the racist terminology and stayed focused on the game. There was a camaraderie among the Asahi and their fans that went beyond stereotypes. By sticking to the rules and presenting themselves as a professional club the team broke through the barriers of racism.

The genius behind the Asahi was Harry Miyazaki, who coached the team from 1922 to 1929. Miyazaki’s vision was a team that could compete with the larger, Caucasian teams of the area. At first, the team did not do well. Miyazaki felt that the best way for his players to compete with the larger Caucasian teams was to play smarter. He taught them to play with finesse. He taught them to use their size – and their wits – to their advantage. They learned to bunt, to pitch and to steal bases. According to George, Miyazaki invented the “suicide squeeze,” in which players on first and third would start running before the batter hit, then the batter would bunt, causing the infielder to scramble after the ball and forget about the players heading for home. “That’s all he worked on, fielding and the finer points of baseball,” says George. As George stands beside the cardboard cutout of Harry Miyazaki, it is easy to see he is standing next to his hero.

A Commitment To Fair Play And Hard Work

In addition to inventing what the press termed “smart ball,” or “brain ball,” Miyazaki recognized the importance of early training, and started three levels of youth teams, beginning with children as young as nine. He became the most influential coach in the Asahi’s history. From 1926 on the Asahi won championship after championship, until World War II brought everything to a halt.

In 1942, Japanese-Canadians were moved to internment camps in the B.C. interior. Young George wound up in a camp in Kaslo. It was the same camp the pitcher and the catcher from his favourite team, the Asahi, were sent. The players continued playing baseball in the camps, helping to raise morale. The games were played after church on Sundays, and the first boy to get to the game got to be the batboy. It was a position that usually went to George, the fastest runner. During these games George dreamed of one day becoming a catcher, because the catcher got to wear all the great equipment.

After the war ended, everything did not return to normal for Japanese-Canadians. They were given a choice of moving east of the Rockies, or being deported to Japan, despite the fact most had been born on Canadian soil. “This was so funny to me,” explains George. “How could I go back to a country I had never been to?” George and his family were relocated to Farnham, Quebec, to a camp that had held German POWs during the war. This was in 1947, two years after the official end of the war, the same year Jackie Robinson played in Montréal and won over the crowd.

For curator Grace Eiko Thomson, the Asahi exhibit “has nothing really to do with baseball.” Grace knew that the baseball fanatics around her were eager to see their heroes immortalized, however, she wanted the exhibit to explore the social implications of the Asahi. She also did not intend for the exhibit to be another demonstration about the injustices of the Japanese-Canadian’s internment. “Baseball was a vehicle to talk about what happened to them,” she says. “How they conducted themselves during this time is the real story.” The Asahi were an example of what could be accomplished by working hard and playing fair. They became an important symbol in the community, something that people could identify with. “These are the stories that really need to be told,” she says earnestly, her cheeks still flushed from a full day at a peace rally in downtown Vancouver. It is clear that Grace’s commitment to justice extends into the future as well as the past.

“Baseball was a vehicle to talk about what happened to them.”

By playing fair – and well – the Asahi gained respect not only in their own community, but also in the larger community. Their accomplishments were recognized in 2003, when they were inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame. In 2005, the B.C. Sports Hall of Fame followed suit by honouring the Asahi Baseball team.

Baseball is just a game, and the Asahi were just players. As George says, “a ball is a ball and a strike is a strike.” Sometimes, however, a baseball team hits one out of the park. That is what the Asahi did with their commitment to fair play and hard work. The Asahi were a powerful force in the community, levelling the playing field for generations to come. Says Grace, “Yes, this is what happened to them, they were interned, but this is what they did. That’s why they were wonderful.”