On any given day, you might find Huynh Han Kuang settled in his recliner, watching TV in his living room while his wife, Hui Minh Lee prepares a delectable meal, likely a unique fusion of Chinese and Vietnamese flavours. Both Kuang and Lee are residents of Surrey, BC, but are ethnic-Chinese born and raised in Vietnam. They came to Canada as refugees over three decades ago, two of the hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese who, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, fled their homeland in search of a better life. They have adapted well to Canadian life but have not forgotten their roots or the hardships they endured to get where they are.

“It was worth it. I was able to escape the Communists. I lived without freedom, and I was constantly in fear,” says Lee when asked if she ever had misgivings about her treacherous journey from Vietnam. “Despite all the trials I faced, I did not regret it.”

The turn-around year in Lee and Kuang’s lives was 1979, the peak of the Vietnamese exodus. Packed into small, rickety fishing boats, the people who would soon be known as “boat people” by the rest of the world, braved violent weather, starvation, dehydration and pirate attacks to journey across the South China Sea in hope of a new start. For those who survived the trek, some of the reactions from their neighbours were far from hospitable. Many countries refused to allow them to land permanently. Others, partly because of the great number of people arriving on their shores, denied them even temporary refuge. Occasionally their landfall was prevented by gunfire or by pushing boats filled with refugees back into open water.

A Country In Distress

The migration was spurred by 30 years of war—first with the French and later with the Americans—as well as by political hostilities between the North and South Vietnamese governments. In the wake of the Communists’ rise to power in South Vietnam, the economy—and indeed the entire country—was in shambles. Businesses, predominately those owned by ethnic Chinese, were expropriated; farmers were stripped of their land and as many as a million people were sent to “new economic zones” and “re-education camps‚” meant to persuade people to embrace communism.

This is what Kuang faced while his friends and neighbours, one by one, fled the country. Eventually, he decided to join the mass migration, but to escape the country by boat normally meant up to a year of careful planning and a hefty payment to smugglers. Luckily, a relative owned a converted fishing boat, and Kuang was given free passage.

With only a few articles of clothing, a little food and water, and some medicine, Kuang travelled by van to a village near the sea, where he and approximately 300 others waited for passage. As he stepped into the dinghy that would ferry him to his relative’s boat, Kuang suddenly became unsure of his plan. “My goal was to leave, but after I left there was no guarantee that I would ever be able to return,” he says. “All of my family and friends and this place that I’d grown up in. I didn’t know if I would ever see it again. That feeling is very hard to describe.” When he realized the boat was so overcrowded there wasn’t enough room to sit, Kuang became dismayed. “At that point there was nothing I could do. Everything was out of my hands.”

The Painstaking Price To Pay For Freedom

Kuang’s boat set sail for international waters during the night, but less than 24 hours later heavy winds forced it to turn back. The boat anchored near the departure point and waited for a calmer night. When it finally reached international waters, Kuang saw an opportunity to jump ship to a much larger vessel—boat number 2736‚—which carried over 1,000 passengers. In his rush to leave, he had to abandon his luggage. Despite boat 2736 being larger, there was no extra room for comfort. Kuang and his shipmates were forced to crouch in the humid darkness of the hold, where a young man just a few seats away from Kuang suffocated and died. “When I found out about the death” Kuang says, “I asked myself, ‘Why? Why did I throw myself into this situation? What did I put my life on the line for?’ The answer was just one word: freedom.”

Soon after setting sail again, the passengers spotted pirates. The young and able-bodied men armed themselves with whatever was available—staves, knives, jugs of gasoline—to prepare for a fight. The pirates chased and circled them for hours before deciding to back off. A few days later, the boat experienced engine failure; it took seven days before it was able to reach Malaysia. During that time, Kuang’s only sustenance was a small amount of water.

After almost two weeks at sea, Hyunh’s boat reached its destination, but as it drifted into the harbour, stone-throwing locals tried to ward it off. To make matters worse, the Malaysian coast guard refused the passengers permission to disembark. Instead, they provided them with fresh water and pointed them in the direction of Indonesia —another day’s journey for the suffering boatload of refugees. With no options available, they sailed on.

Once inside Indonesian waters, Kuang’s boat was escorted by a navy gunboat to a remote island, where the passengers were finally able to set foot on dry land. The island, however, had nothing to offer them: no food, no shelter, no running water. The refugees had to chop down trees and collect leaves to build shelters. For the first couple of nights, Kuang slept on a tarp laid out on the beach.

Days passed before the Indonesian authorities arrived with UN supplies of canned food and instant noodles. “On the island, I had to drink from the streams, which eventually caused dysentery. I thought I would die on the island,” Lee remembers. “Every day was very painful and lonely. Sometimes I would just sit and stare out into the ocean. Luckily I had my Bible with me, and I knew my life was in God’s hands.”

Love In The Time Of Hardship

Life in no man’s land was difficult, but it had a silver lining. Though they had both been passengers on the same boat, Kuang and Lee didn’t meet until Kuang needed someone with sewing skills to replenish his disintegrating wardrobe. Kuang asked Lee to help him fashion two pairs of shorts from his one remaining pair of pants. In return, Lee asked him to help her collect firewood from the jungle. A relationship that would continue well into the next century had begun.

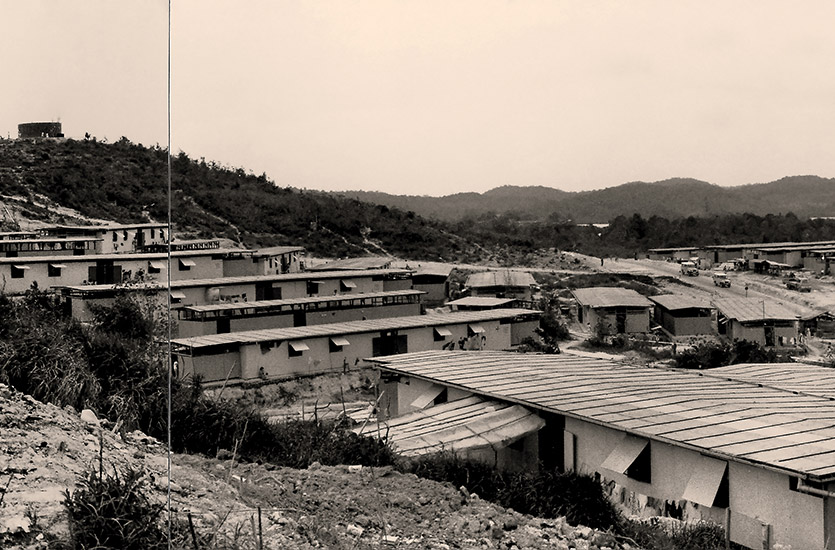

Eventually the passengers of boat 2736 joined nearly 30,000 other refugees at a processing facility on Pulau Galang Island. “In Galang, we lived in barracks that housed 100 people and slept on giant beds that fit 25 people each,” Lee recalls. “But I had hope now, because I knew I would be accepted to another country.”

Lee was the first to be accepted for resettlement. She arrived in Canada in October 1979, and soon afterward nominated Kuang for sponsorship through the church that helped her immigrate. It took a year for Kuang and Lee to be reunited in their new country. It’s been more than 30 years since they arrived in Canada, but they will always remember the ordeal that gave them freedom and brought them together.