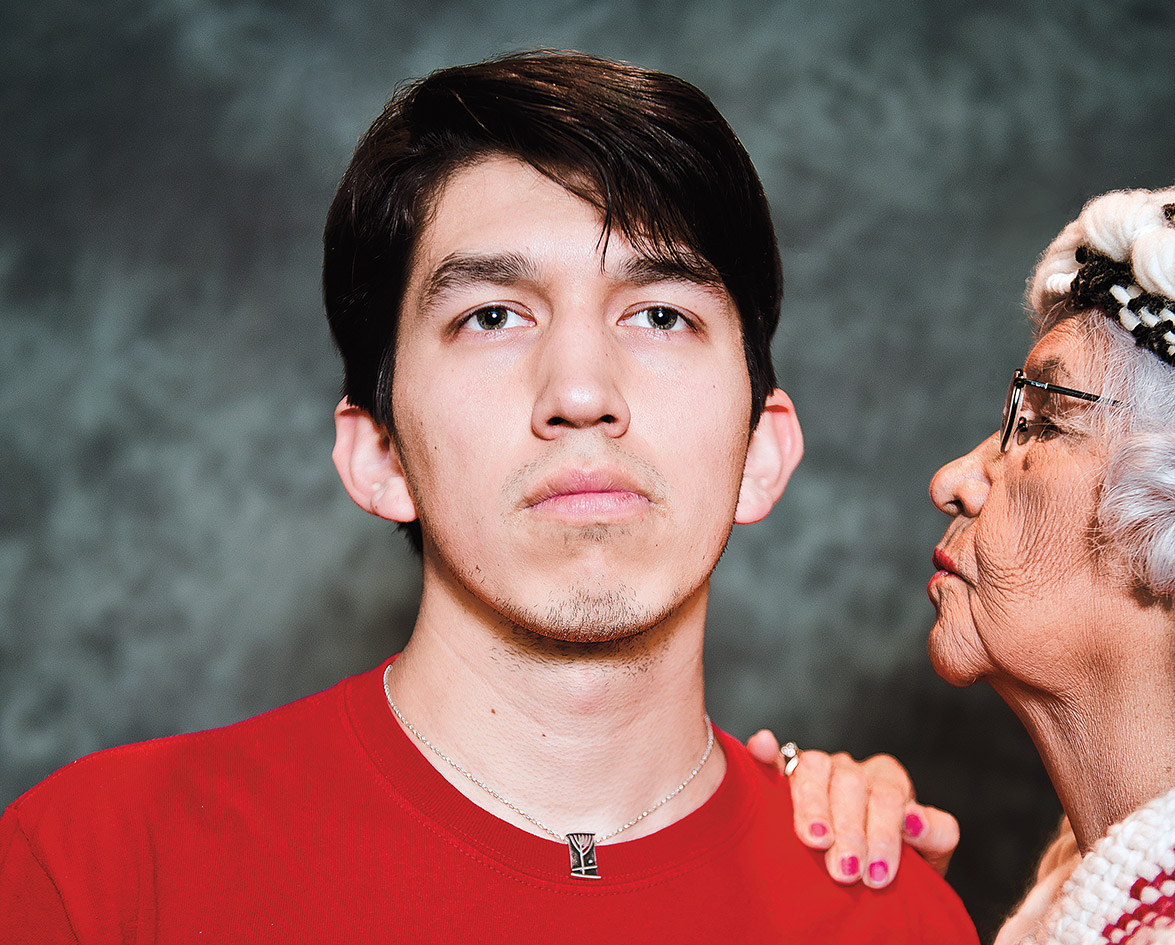

Armed with an iPad and a Twitter account, 21-year-old Dustin Rivers of the Skwxwú7mesh and Kwakwaka’wakw nations has been spreading his language-saving message by blogging, tweeting and podcasting. The self-proclaimed “language revitalization activist” also teaches community language nights on the Capilano reserve in North Vancouver. And though he has been on track toward learning his language since he was a kid, the past year has seen Rivers’ efforts accelerate to a point where he has become a teacher, a community organizer, and a poster child for language revitalization.

“If you want to learn the Squamish language, you should talk to Dustin Rivers.” These words are repeated frequently when curious visitors arrive at the Capilano band offices. Rivers says that he’s humbled that his own mentor and language teacher, Vanessa Campbell, is now referring him to community members eager to learn the language. “When I found out she put that much weight behind what I was doing, it was really monumental for me to hear that from my mentor—the person who is the biggest teacher in my life when it comes to language.”

Status Of Squamish Language Disheartening

Skwxwú7mesh Sníchim is the language spoken by the Skwxwú7mesh people, whose traditional territory includes some of Vancouver. Both the Skwxwú7mesh language and nation are colloquially referred to as Squamish. As one of British Columbia’s 32 distinct First Nations languages, the Squamish language is traditionally passed down orally from generation to generation; it is the way its speakers have related to each other and the world around them since time immemorial. However, since European colonization reached the West Coast, the number of fluent speakers has dwindled to an estimated 0.01 per cent. Today, it means that in a nation of approximately 3,324 people, Rivers estimates, there are four fluent speakers left.

The First Peoples’ Heritage, Language, and Culture Council (FPHLCC) released a report in April 2010 outlining the status of B.C.’s First Nations languages. The report has brought to light some dismal statistics: only 5.1 per cent of B.C. First Nations people are fluent speakers of their language, which puts all 32 of the languages included in the study as severely endangered, nearly extinct or already sleeping (extinct).

The dramatic loss of fluent speakers began with colonization and the Canadian government’s historic policies to assimilate First Nations people into English-speaking, non-First Nations society. A major part of the assimilation process was the forced removal of children from their families and placement into church-run residential schools, where First Nations languages were strictly banned from use. Part of the process included brutal physical and emotional punishment, resulting in children feeling fear and shame for speaking their language. As the report states, “many residential school survivors, their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren still feel the effects of the loss of their traditional First Nations languages.”

For a nation whose way of life has been drastically affected by the development of Canada’s third largest city within their traditional territory, there are some challenges in creating environments where the Squamish language is spoken exclusively—the influence of the English language is everywhere. Because there aren’t many fluent speakers left, there aren’t many opportunities for the language to exist without the influence of English. “It is difficult at times, because English is my thinking language. It requires a conscious thought to really switch over [to Squamish],” says Rivers. Creating environments where only Squamish is spoken triggers the mind to operate in that environment. “And those don’t exist right now.”

”Where Are Your Keys” Organization Helping To Keep Languages Afloat

You could say it started with a tweet. That is how Rivers learned about the language-learning method called Where Are Your Keys (WAYK). Based out of Portland, Oregon, WAYK was developed by Evan Gardner and his associate Willem Larson to get people speaking their language as quickly as possible. During a phone conversation from Bend, Oregon, Gardner describes WAYK as “an open-source, community-based method designed to accelerate the language-learning process.” The game incorporates sign language, special rules, and techniques that help transfer language faster from one person to another. A typical game has players sit around a table where they interact with simple objects, such as rocks, sticks and pens. Players learn by passing questions and answers about the objects back and forth.

Larson and Gardner had been working with First Nation communities in Oregon and Washington for about 10 years when they began to develop a larger web presence. About two years ago, Larson spotted a tweet from Rivers on Twitter. “[Rivers’ tweet] said something like, ‘I want to learn my language within the next such and such timeframe,'” Gardner explains, “We emailed him back and said, well, we know a way. Any community that actually wants to bring their language back just needs to have someone that says, ‘Okay, I’ll do it’.”

Learning The Language While Bringing The Community Together

For the Squamish nation, Rivers has become a leader for those who want to learn their language. With the help of Gardner and Larson’s method and mentorship, Rivers has organized community language nights for his people. The language nights are attended three times a week, by up to 24 dedicated learners ranging from 10 to 64 years of age.

The language nights are also bringing his community together. “I noticed people that wouldn’t normally interact with each other are now in an environment where they have a shared interest and they are interacting and building a relationship, becoming friends or community members again,” Rivers says. And they’re having fun while learning, he adds: “When there is laughter present, people tend to learn a lot more. So if it’s fun and there are a lot of funny and silly moments—and people are laughing, it means that people are learning.”

Slow Yet Steady Results

So what is needed to bring a near-extinct language back to life? Ten per cent. One in ten members of the Squamish Nation need to be fluent in the language in order for it to remain safe from extinction. Rivers has a plan to make that happen. “I have an eight-stage strategy that I’m following, developed by American linguist, Joshua Fishman. His strategy helps you identify where your language is on the scale, so you can appropriately accomplish the next step.” Rivers says that Skwxwú7mesh Sníchim is still in the early stage: getting an adult generation of speakers who act as language apprentices, and as bridges between elders and the youth. He says, “if we’re there and we start creating newspapers in Squamish or writing books in Squamish, they’re not going to be entirely useful until there are people who are able to read them.” He says that time and resources spent on producing written learning tools could be better used to address the issue of where the language is at now, and getting it to the next level, which is creating an integrated group of active speakers where the language is used habitually or exclusively.

Rivers projects that he will become fluent in two years. “Fluent to me means being able to create and command the speech, understanding the language to a point where I can express complex ideas, layers of thought, [becoming able to] really dive deeper and deeper into a subject, having philosophical or societal discussions in my language,” he explains. In five years, he hopes to develop “language nests” and residences in his community. “I want to be able to get four other people to live together for a year or so, where, in the residence, we only speak Squamish,” he explains. Rivers describes a language nest as a preschool-type environment for kids where they only speak the Squamish language. He says his nation is working towards developing an immersion school right now for kindergarten to grade three, but that they’re running into problems of creating fluent speakers: “I think that with Where Are Your Keys, I’ll be able to accomplish that.”

For the Squamish community language nights, communicating with one another is essential to its success. Rivers understands that many people lead busy lives, and access to fluent speakers and immersion environments is not always practical. This is what led him to develop Squamish language podcasts: weekly five-minute episodes designed to supplement the language nights. The podcast, Na Tkwi Sníchim, can be downloaded from the Squamish Language website—a website Rivers maintains with the help of his sister, Cheyenne La Vallee, who is also on her way to becoming a Squamish language instructor.

Rivers credits the Internet with helping to spread his message and allowing people to associate his name with language revitalization. Once the word started getting out that Rivers wanted to save his language, he felt he needed a title to put beside his name. He came up with the term: language revitalization activist. The title means that he’s not only getting the word out there, but he is using activism as a tactic to accomplish his goals. “It revolves around organizing. It’s not just talking about the issue, being public about it, or being an unofficial spokesperson, but also organizing language classes, the immersion gatherings, and doing all the work in that.”

”This is one of the most pivotal issues that my generation will ever have to face.”

Exposure To Activism At An Early Age

Rivers’ dedication to community activism and interest in language revitalization can be attributed to his great-grandfather and grandmother, respectively. Rivers’ great-grandfather, Andy Paul, was an “unofficial lawyer” and indigenous rights activist who actively fought court cases, but refused to give up his Indian Status in order to join the bar. Paul was also involved with the formation of several monumental organizations including: Allied Tribes of B.C., the Native Brotherhood of B.C., and the North American Indian Brotherhood (now known as the Assembly of First Nations). Rivers credits his great-grandfather for shaping his interest in political activism; “He was one that didn’t follow the mold and really set out to create his own path to help his community and his people. He did that in a really big way, and so he was always one of my heroes.”

It was Paul’s daughter—Rivers’ grandmother, Audrey Rivers—who instilled in Rivers the importance of learning the Squamish language. “From a young age, I always knew [revitalizing the language was] something that I’m supposed to be a part of,” says Rivers. His grandmother kept him connected to a language that she herself had forgotten, due to 10 years spent in the residential school system. “She knows bits and pieces [of the language] and she raised me until I was six, so she always made sure that I was aware that the language was important and that I should be learning it.” Rivers fondly recounts that he couldn’t go outside or watch cartoons until he listened to a half-hour of tapes of language and traditional singing. This early influence was important to Rivers becoming aware that his language was at risk of becoming extinct. “This is one of the most pivotal issues that my generation will ever have to face because if the language isn’t revived now, it will never be really revived.”

Rivers was recently named The Most Inspiring First Nations Language Activist in the Georgia Straight‘s 2010 Best of Vancouver issue. He laughs when asked how he feels about the title. “That’s funny, I didn’t even know about it, and one day, I woke up in the morning and my Twitter was exploding with people who were re-tweeting it,” he says. “I thought it was really quaint and cute and funny. It’s an honour and I really enjoyed that.” Rivers has kept his good humour and humility amidst all of the media attention he’s been receiving over the past year or so, which is something that he credits to his family and his upbringing. “One of the things I’ve always been taught since a young age, which is one of the most important teachings in my community, is that people are watching you and that your actions and your behaviour reflect on your family and, when you are outside of your community, on your people as well.”

Alongside Rivers’ name on his Twitter account is a quote: “Sometimes a leader, and sometimes one who leads.” To him there is a difference. “We’ve got political leaders, cultural leaders [and] we have spiritual leaders within our communities,” he says. “But leaders aren’t always the ones that lead—they don’t lead us to new places all the time. Leaders can be really successful at keeping us in the same spot. Those who lead, though, it’s a really specific thing that you are accomplishing: you’re leading something somewhere, you’re moving a community or a people or an issue to a new place. You can’t lead and be stagnant.”