The note his mother wrote excusing him from school wasn’t for a dentist’s appointment. He wasn’t ill and staying home to watch cartoons in his pajamas either. It was the day the Royal Ballet, starring Margot Fonteyn, was in town and David Y. H. Lui had convinced his mother to take him. What young Lui didn’t know was that by skipping classes that day he was, in fact, setting in motion the direction of his life’s work.

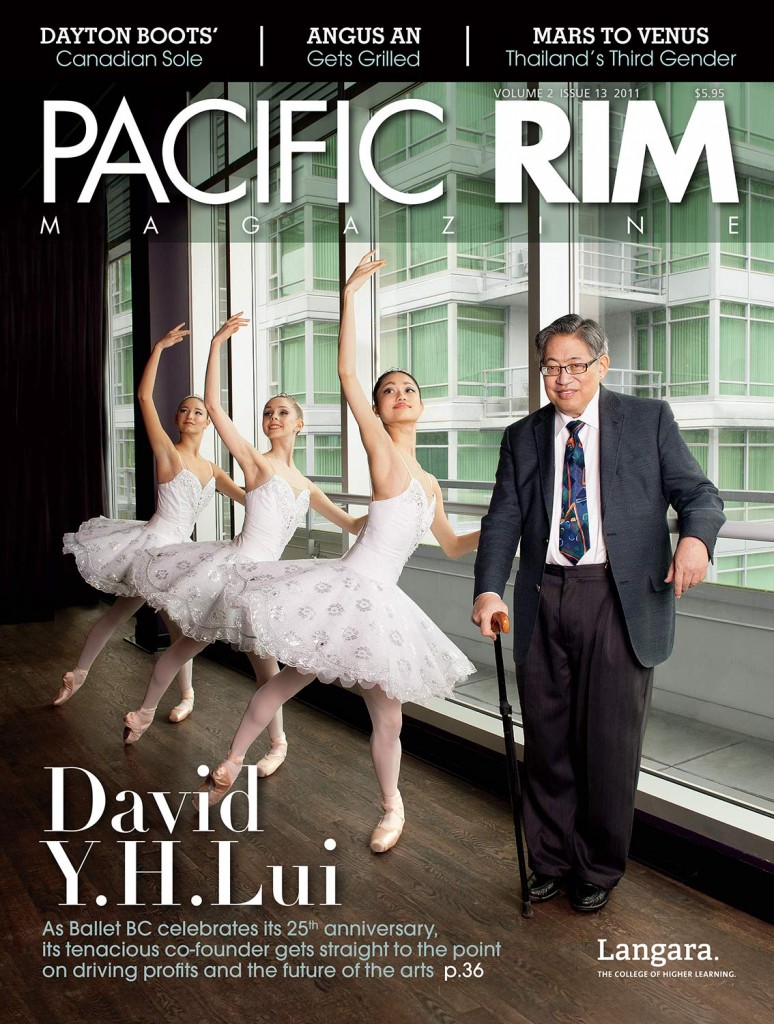

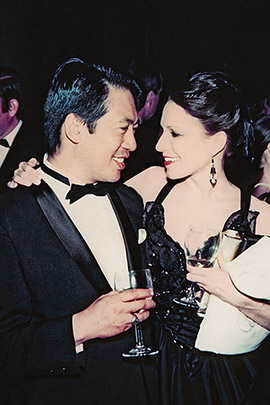

Today, sitting in his apartment in Vancouver’s Performing Arts Lodge overlooking Stanley Park, 66-year-old impresario Lui is surrounded by a cluttered collection celebrating his successes; a top hat sits on a table while ballet pointe shoes peek out from a bookshelf. Vintage dance posters and Asian masks cover the walls. Evidence abounds that he has led an inspiring and extravagant life.

An Impressive Resumé

Well-known for his role in designing the on-land cultural program for Vancouver’s Dragon Boat Festival, as well as co-creating Ballet BC with Canadian ballerina Jean Orr, Lui has been a seminal figure in B.C.’s arts scene. His influence spans over 40 years and includes events such as hosting operatic soprano Dame Joan Sutherland, the Canadian National Ballet and Jacques Brel in his own David Y.H. Lui Theatre. He was also part of the initial think-tank formed by Jimmy Pattison tasked with conceptualizing Vancouver’s Expo 86. Most recently, the Scotiabank Dance Centre named its rooftop garden in Lui’s honour. His creative influence and passion for the performing arts has been recognized with an Order of Canada as well as induction into BC’s Entertainment Hall of Fame.

An Early Start In Culture

Vancouver-born Lui credits the support of his parents, Chak Fun and Irene Jok Wah, who encouraged him to follow his interests in classical theatre and dance. The two, a businessman and housewife, raised their family of four in Vancouver’s Dunbar area—not a typical neighbourhood for a Chinese-Canadian family in the 1950s. Lui says that while they were not very knowledgeable about the arts, his parents were sensitive to his interests and encouraged him by buying classical music records, and providing him and his brother with violin lessons.

Lui graduated from Kitsilano High School and entered the University of British Columbia in the mid-60s. As a university student he didn’t immediately identify with the campus’ “flower child” culture, but like most of his contemporaries, he did subscribe to the “do what feels good” mentality of the times. Unfulfilled by his commerce classes, he sought out opportunities to explore his creative side and, while still a student, got a job as classical chairman of UBC’s Special Events Club. Lui went against the tide of popular hippie culture and for his very first event invited the Royal Winnipeg Ballet to perform for students—an early demonstration of fearless ambition. He then went on to hone his skills with UBC’s Musical Society (MUSSOC), a group known for offering near-professional calibre and large-scale productions on campus.

When looking back on how he launched his career right after graduating from UBC, he brushes it off saying it was “very much like Mickey and Judy found a barn and are going to put on a show,” referencing the classic Rooney and Garland musical Babes in Arms. “You opened the door, put on a show, had a business and kept it going somehow.”

Lack Of Funding No Excuse For Artistic Hardships

Lui makes his accomplishments sound so easy. But times have changed. Now with B.C.’s theatre, dance and arts communities facing a sudden $20-million cut to grants and funding from the provincial government, many companies and organizations are struggling to survive. But Lui, who has never received any government grants, isn’t so sure these communities should point to current government funding as the main reason their budgets are so tight.

“It’s easy to blame everything on the money, but it is not just the money,” says Lui, noting that past governments, including the NDP and Socreds, also cut funding to the arts. “They have never appreciated the value of culture,” he says of provincial politicians, and suggests that resolving funding shortages should fall on the shoulders of artists and audiences alike.

“We haven’t done anything about teaching ourselves about sustainability,” he says. “Why can’t we be more creative about how we sustain ourselves?” Lui speculates there is a perception in the performing arts community that artistic ventures cannot make money and need outside funding to flourish. He thinks it is not the government but the theatre and dance communities themselves that need to change how they operate.

“There is a terrible malaise that has happened. People feel a sense of entitlement to a grant,” says Lui. “We are our own worst enemy in that regard.” Lui believes that theatre and dance companies in particular, and the arts community in general, could benefit from adopting a more traditional profit-driven outlook, where artistic directors and producers start thinking more “about what they are doing and why they are doing it.” Lui bluntly stamps his cane against the floor for emphasis. “Do things that the public wants to see. I’m not interested in paying to see self-indulgent theatre, dance or anything.”

Lui concedes that there is still a need for government funding to bring new and unknown works to the stage. Yet he notes how during the recession in the 80s, when venue and company coffers were suffering, producers became more creative by using their resources more frugally. “I’m not sure that’s what’s happened this time,” he says.

Sustainability In The Arts World

Joy Coghill, Lui’s neighbour at the Performing Arts Lodge and a recent Gemini Humanitarian Award winner, agrees that a different and more creative approach is needed to keep the performing arts sustainable. She understands first-hand the difficulties of fundraising for arts causes, referring to her own challenges seeking donations to first build and then finance the Performing Arts Lodge, a housing community for people, primarily seniors and the disabled, who have worked in the performing arts and associated industries. Coghill believes fundraising is now an occupation based on lists and mail-outs and less about sharing enthusiasm for a cause. People feel burnt out and inundated with requests for donations, she says. When times are tough, theatre and dance organizations often cannot compete with other causes such as homelessness and cancer research.

“The arts are the only thing, for the average person, that deals with their emotional release.”

When asked about other ways arts communities can increase their profile, Coghill points out that Vancouver’s independent Pi Theatre has offered free tickets to entice attendees and launched the popular “See Seven” series, an opportunity to see, for a set price, any seven performances staged by independent theatre companies at different venues throughout Vancouver. In fact, festivals such as the Fringe and Bard on the Beach seem to have consistently high attendance numbers, pointing to the importance of performance packaging and branding. “Maybe this is something we should look at and use more,” Coghill says.

Vancouver’s Apathy Towards Theatre And The Performing Arts

Lui and Coghill are also in agreement that Vancouver—more than other Canadian cities—suffers from less-than-enthusiastic audiences. They acknowledge that Vancouver is a “young town” without a strong tradition in theatre and other performing arts. “It’s a lack of transference of the culture from one generation to the next,” says Lui. “A lot of people come here and live here for the beauty and the ‘fabulous’ and the whatnot,” says Lui in an exaggerated posh accent. “But they come without a lot of investment in the place.” Coghill adds that people don’t move to Vancouver for the performing arts, either as an occupation or as an attraction, and admits that the natural scenery is the city’s biggest draw. Vancouver has a lot to offer its residents and there is a lot of competition for their time and dollars, with outdoor attractions that cost nothing to use.

Lui believes that society as a whole is forgetting how important arts and culture are to its health and well-being, an opinion strongly shared by Coghill. “You’ve got to remember that the arts are the only thing, for the average person, that deals with their emotional release,” argues Lui. He believes that without the ability to escape the stress and pressures of work and family there will be a reduction in the quality of life, leading to greater social and financial costs to society in the future.

A lack of awareness of theatre and dance classics by younger audiences has larger ramifications than low-ticket sales and revenue loss. For Lui, it all goes back to childhood. He recognizes his own good fortune to have had family support to explore his creative interests when he was young, and emphasizes that not all children have similar access to private music or dance lessons. Primary public education needs to once again focus on allowing kids to explore and play, listen and create. Culture has lost its place in society and needs to return to the school curriculum. Lui thinks that if the government funded more early creative education, there might not be as much of a need to keep the arts afloat through grants. “Once [children] grow up valuing the arts,” says Lui, “they will elect people who value the arts, support the arts through attendance and donate to causes close to their hearts.” As he battles Parkinson’s disease, Lui is still passionate about the future of Vancouver’s performing arts community. Retirement isn’t on his agenda. He is working toward bringing the National Ballet of Cuba to Vancouver in February 2012, and is also in the process of recording a video of his life stories chronicling the iconic performers he’s met over his career, including people such as Martha Graham, Shirley McLaine and Lee Strasberg. “I’m tenacious. I’m like a pit-bull terrier,” he says. “I don’t think I am obsessive compulsive, but I am whatever a nice word is to describe that.”

*David L.H. Lui passed away in September, 2011. He will be remembered for the impact he has had on the arts community in Vancouver.