At the 1936 summer Olympics in Berlin, Germany, African-American track and field athlete Jesse Owens stood defiant against the host country’s ruling political party, Adolf Hitler’s National Socialists. Owens dominated in the track and field events, bringing four gold medals home to the United States. Upon his return, he was greeted with a hero’s welcome. Owens’ Olympic performance was a catalyst for change, but racial segregation in sports persisted for many years following his success.

In 1947, a young second baseman from the Negro League named Jackie Robinson became the first black player to break into Major League Baseball. Robinson proved himself a worthy addition to the Brooklyn Dodgers, racking up a series of impressive stats, including 1947 Rookie of the Year; National League Most Valuable Player for 1949; six consecutive All-Star Game appearances; and a World Series win in 1955. In spite of these on-field successes, Robinson was the subject of racial discrimination from both players and fans. He persevered in the face of this discrimination and made an indelible mark on professional sports and the civil rights movement.

Larry Kwong was born in Vernon, British Columbia in 1923 to immigrant parents. The Kwongs were one of only three Chinese families living in Vernon at the time. Kwong was the 14th of 15 children and had older brothers who played hockey.

“They played hockey as a fun game, but I was the only one who wanted to play hockey for a living. In those days, Chinese never believed in sports as a living,” Kwong explains.

A Passion To Play The Puck

His passion for the game of hockey was undeniable; he and his friends would often walk miles just to find ice to play on. Kwong credits those early days of playing pond hockey with his friends for the development of the skills that drove him towards a career in hockey: “We learned by playing on the ponds to stick handle. We would only have one puck and everyone would be going after it so you’d try to keep it as long as you can.”

When artificial ice came to Vernon, Kwong and his friends would sneak into the rink and hide in the dressing room, waiting for the caretaker to leave. “We would go out…and play at three in the morning with a nice sheet of ice in front of us.”

One benefit that players in the senior league received was jobs in the off-season. “All the players worked for somebody. They would pick out one of the better businesses and ask them to give us a job,” says Kwong. In Trail, one of the “better businesses” to work for was the town smelter. Kwong’s teammates from the Smoke Eaters all got jobs there.

Racism Rears Its Ugly Head

“When I made the team, they tried to get me a job there. They said, ‘No Chinese allowed,’ ” Kwong recalls. He was given a job as a bellhop in a hotel.

In addition to the racial discrimination Kwong was experiencing at home, the global political climate of the early 1940s was troubled. The West Kootenay Hockey League, where Kwong was playing, suspended operations because of World War II. At that time, many young men were enlisting in the Canadian Forces and were being deployed overseas. Kwong remembers, “At that time they didn’t want the Chinese to be in the army. Then near the end of the war they decided to draft us. I was drafted and I went and had my basic training.” While fully expecting to be deployed overseas like so many others brought into the service of the military through conscription, Kwong’s talent for hockey meant he had another role. They drafted him to play hockey to entertain the troops.

They played hockey as a fun game, but I was the only one who wanted to play hockey for a living.

In 1945 Kwong returned to play a cup-winning season with the Smoke Eaters. It was during that season that a scout for the New York Rangers noticed him. “I was asked if I would like to play for them [Rangers farm team, the New York Rovers]. I was happy to play anywhere in the NHL,” says Kwong. “I was so glad just to be asked by a team.”

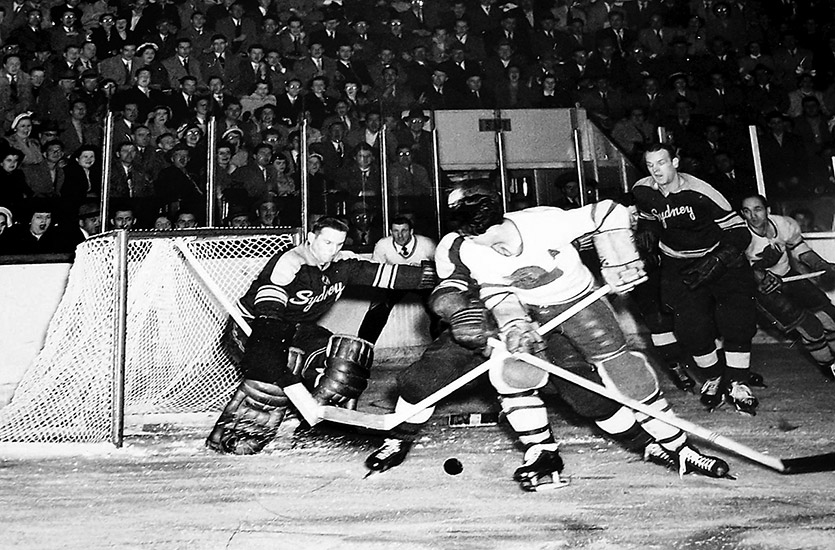

Kwong’s arrival created something of a sensation. Before his first game at Madison Square Garden, mayor Shavey Lee presented him with the key to Chinatown. He appeared in a television commercial for Bristol shaving cream. It was at this time that he got another nickname: he was dubbed “King Kwong” by the New York press.

Kwong took this opportunity to showcase his talents and became the highest scorer for the Rovers, but his shot at the NHL still wasn’t certain. They brought everyone else on the team up to the NHL before Kwong. The big-league call did finally come. He would get the chance to don a New York Rangers uniform and face off against the Montreal Canadiens on March 13th, 1948, at the Forum in Montreal. Kwong sat patiently on the bench through two periods of play. Finally, in the third period, he got the nod from coach Frank Boucher. The moment the blades of his skates hit the ice of the Montreal Forum, Kwong made one of the first great strides in the fight for equal rights for minority athletes.

Well Played, King Kwong

While thankful for his chance at the big leagues, Kwong saw the writing on the wall. “When I saw that they only gave me a couple of minutes on the ice, I said, ‘Well, this is not the club for me.’ ” Other organizations weren’t so quick to dismiss Kwong’s skills. During his time with the New York Rovers, the president of the Quebec Senior Hockey League’s (QSHL) Valleyfield Braves recognized his talent and made him an open-ended offer to join his club. Kwong says, “He told me anytime I would want a job he would hire me, so when I decided to leave New York I contacted him and went to play there.”

There was no shortage of talent in the QSHL. Kwong found himself up against legendary players. “We had players like Doug Harvey, Gerry McNeil, Jacques Plante—they were all playing in our league. I played for coach Toe Blake before he went to the Montreal Canadiens. With him we won the Canadian championships.”

Kwong continued to compete in professional hockey in the QSHL until 1956, when he decided to take his talent abroad. He recalls, “I told my brother that I was going to go to Europe, just see what it was like, and I’d be back. I ended up staying for 15 years.” He spent those 15 years in Switzerland, playing and coaching hockey as well as teaching tennis. He returned to Canada in 1972.

Kwong has since retired, but he still keeps a keen eye on hockey. “It’s a different brand of hockey now. There’s less puck handling by the players. We used to stickhandle very well, which we learned playing hockey on the ponds, with 20 kids after one puck.” He continues, “We didn’t wear helmets at that time, and if you were lucky you got a pair of shin pads. In our day, you hardly ever saw concussions. Now you’re seeing all kinds of concussions.”

While his time in the National Hockey League was brief, Larry Kwong accomplished two things: he achieved his dream of playing professional hockey at its highest level, and he helped pave the way for other minorities. He continues to hope they get their own shot like he did.

The evolution of racial diversity in hockey has continued since Kwong’s playing days. Today the Asian community is represented in the NHL by the likes of former Vancouver Canuck Paul Kariya and the Colorado Avalanche’s Brandon Yip. In addition to veteran Asian players, Vancouver’s Zachary Yuen recently took to the ice as a newly drafted player for the Winnipeg Jets. With racial diversity now more common in the NHL, each of these players owes Larry Kwong and others like him a debt of gratitude.