Dressed in emerald green, Marilyn Monroe smiled and waved as she stepped out of a small plane, walked onto the platform and down the steps at the old Vancouver Airport. Embodying beauty and charm, Monroe brought a bit of Hollywood to the tarmac. On that day in 1953, two 15-year-old boys got on their bicycles and rode 15 km, from Vancouver Technical High School to Richmond, to get a glimpse of their movie star crush. The friends were able to get close enough to study her every move. Monroe was starring in River of No Return, to be filmed in the Rockies of Alberta. Knowing that she would be taking a limousine from the airport to the train station on Main and Terminal, the two awe-struck teens hopped on their bicycles once again. They made it there in time to see her wave goodbye to her admirers. Those teenagers were Larry Wong and Wes Woo. Seeing Marilyn Monroe was one of the most thrilling moments in Wong’s childhood—one that he has never forgotten.

Wong has an impressive memory. In 2011, at 73 years of age, he published his first book, Dim Sum Stories: A Chinatown Childhood. In the book, he writes about growing up in Vancouver’s Chinatown in the 1940s and 1950s. I was fortunate to sit down with Wong in his East Vancouver home to discuss his life and find out why it was so important for him to write memories that took place 60 years ago. Bright red walls and black leather couches make up Wong’s eclectic living room decor. A fireplace warms the house. On the mantel sits a white statue of Quan Yin, the goddess of Mercy, a brass figure of the Monkey King, a statue of an imperial couple, and an old weightlifting trophy. There are photos of friends and family, including Wong’s aunt, childhood friend Wayson Choy, and writers Carol Shields and Gail Anderson-Dargatz. Wong chatted with me about the stories that make up his book. He was delivered by a midwife in the heart of Chinatown in 1938. His family lived in a small space in the back of his father’s tailor shop.

In The Early Days

In those days, Chinatown was a close-knit, self-contained, and self-supporting community. The Chinese-Canadians kept their business and family members close by, and tended to remain within the boundaries of Chinatown, where they felt safe from racial discrimination. Wong was the sixth and youngest child to Wong Quon Ho, father and Mark Oy Quon, mother. He had five older siblings, Yung Git, Ching Won, Yung Wah, Mee Won, and Wong Jin Lee (Jennie). Ching Won and Mee Won died before Wong was born. Yung Git died of tuberculosis when Wong was only four years old. He was closest to Jennie despite their seven-year age gap. After their mother died during his infancy, Jennie naturally fell into the role of mother to Wong.

It wasn’t until the last ten, fifteen years that I started to embrace everything that was Chinese.

Jennie was the wild child of the Wong family. As a teenager, she dated non-Chinese boys, to her father’s great disapproval. She often went exploring outside the boundaries of Chinatown, and had her own radio show, Jennie’s Juke Joint. Her rebellious nature prompted her to run away from home when she was a teenager; her brother was just a young boy at the time. Jennie, along with a couple of friends, hopped on a freight train and traveled across Canada. But before she moved away she spent a lot of time with Wong.

Jennie exerted a strong influence on her baby brother. She loved books and encouraged him to learn to read and to use the library at a young age. He remembers Jennie taking him to Carnegie Library for the first time. The very first story that Wong remembers falling in love with was King Arthur and the Round Table. Since then, reading and writing have been an integral part of his life. Jennie died in early 2011. As he spoke of her life and death, I could tell by his quiet tone that he greatly misses her. He dedicated his book Dim Sum Stories to her. Wong’s teen years were marked by the notable absence of his siblings; only he and his father remained. Encouraged by a school counselor, Wong considered engineering as a career choice; however, his interest was short-lived. This led him to a series of disparate career changes.

Trying To Find The Right Path

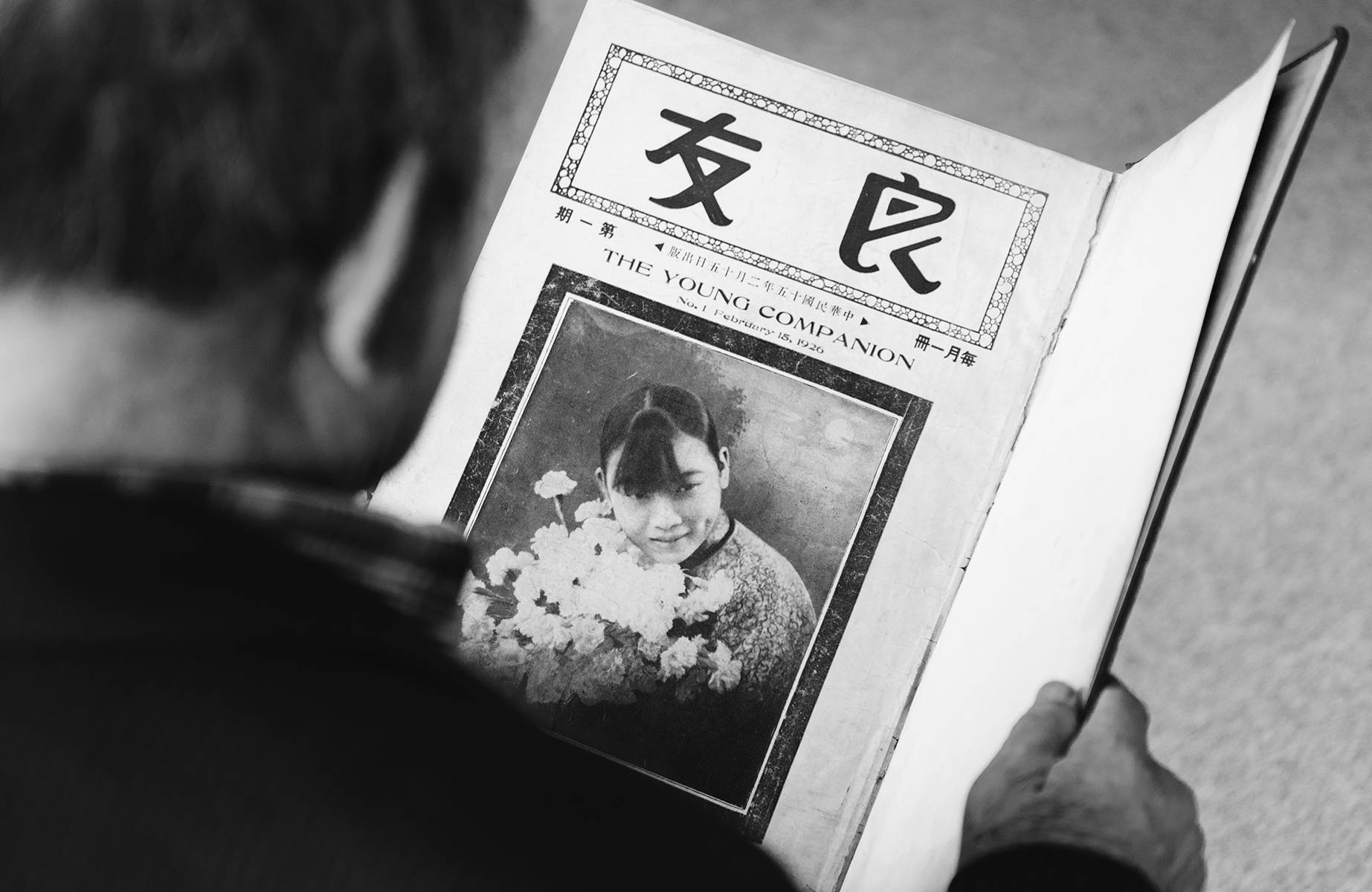

After graduation, Wong did not have enough money to go directly to university, unlike many of his friends. He worked for an English language news magazine called Chinatown News for two years. He started out selling advertising, and was later promoted to head of layout and design.

When Wong had saved up enough money, he went back to school. He studied psychology and creative writing at the University of British Columbia. However, after two years, Wong decided that although he wanted to become a writer, “[university] wasn’t the best way to approach it.” Wong then worked for Canada Post for twelve years. He started as a clerk, filling out order forms, moved up to sorting mail, and later worked the front counter. When Wong was 34 years old, he was hired to work as an auditor for Canada Post in Toronto. Being an auditor meant a lot of treacherous travel during Ontario winters. It wasn’t for him. He left Canada Post and began working with Employment and Immigration Canada. He was laterally transferred back to Vancouver in the 1980s. After 30 years of service, Wong retired from the federal government in 1994. He was finally able to devote time to things that had long been in the back of his mind. He co-founded the Chinese Canadian Historical Society of British Columbia in 2004. He began writing with focus and passion. Dim Sum Stories started off as a one-act play called Sui Yeh (Midnight Snack) before fellow Vancouver writer Jim Wong-Chu encouraged him to turn it into a book of short stories. He also became involved with the Federation of B.C. Writers as a board member, and the Chinese Canadian Military Museum as a curator and secretary. He has kept busy as a writer, with events such as the workshop he gave in the fall of 2011 at Historic Joy Kogawa House, on writing family stories, with former writer-in-residence Susan Crean.

The Healing Powers Of Writing

Writing has been very important for Wong’s personal growth. It was vital for him to write Dim Sum Stories. “I wrote it for myself,” he confesses. Towards the end of the book, Wong explores his identity as a Chinese-Canadian.

He writes that while his father was always sure of his identity, he (Wong) struggled with his. “When I was growing up, I hated being Chinese…[and] anything to do with Chinatown.” He admits: “It wasn’t until the last ten, fifteen years that I started to embrace everything that was Chinese. And because now I know that it is part of my heritage and it’s really who I am, I embrace and try and learn as much history about China as I can…. [As] a full grown adult I started to appreciate my background and heritage. And I’m really embracing it.”

Writing has been a personal journey for Wong; it has served as an outlet to acknowledge his past and to reconcile it. Sitting and talking to Wong, I realized why he needed to write this book. He didn’t want to forget his past. He wanted his memories to last forever. Writing has also been a way for Wong to make peace with his father, who died in 1966, with his youngest son by his side. At the time, 28-year-old Wong had been living outside of Chinatown for three years and visiting his retired father once a week for dinner.

As an adult, Wong says his relationship with his father was good. However, he admits, when he was a teenager there was a rift between them. “There were a lot of harsh words spoken. And I must say I kind of regret it…. In a sense that’s why it’s important that I redeem myself.” Wong explains that his father “instilled into me some sense of morals and good judgment and family values… and I really regret the time that I was really angry with him.” Wong’s search for redemption has come to an end in Dim Sum Stories. “I guess I’m…hoping if he were alive he would forgive me for what I have done. And the reason why I do this, like I say, he instilled this philosophy of do good to others and I think he got it inside of me so much that I really wanted to be sure that I’m still okay with my father…There’s this little bit of me, that God, I hope he’s happy with this.” Wong’s friend, Jim Wong-Chu, has an interesting reflection on being a writer, and the function of personal and cultural memory Wong’s book performs. “The beauty of having a book…is that they can make something that will last forever.” With his book, Wong both honours and preserves the memories of his father and sister. Writing was a vehicle for Wong to make his thoughts tangible. His passion and fervor for history and its preservation is evident in his book and his storytelling. Some writers write because they are inherently good at it. Some writers write because they have a message or story to tell. Larry Wong writes for these reasons and more.