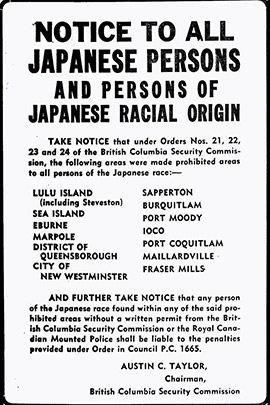

In 1941 anti-Asian sentiment was not new in Canada. With the start of World War II it became focused on Japanese-Canadians in particular. The military successes of Japan in Manchuria and Hong Kong, combined with the attacks on Pearl Harbour and Estevan Point on Vancouver Island, were creating an escalating sense of fear in the country. British Columbia was feeling vulnerable.

While no evidence of subversive activity on the part of the Japanese-Canadians was ever found, they were relocated to internment camps for the duration of the war. Their property was sold off at rock-bottom prices to cover the cost of their incarceration, and they were denied the right to return to the coast for four years after the war. Of course, they had nothing left to return to.

Creating A Better Future By Remembering The Past

Historical theories about the internment debate whether the government was acting out racism or fear of it, but whatever the reasons behind the history of Joy Kogawa’s family home, what remains is a group of people who are taking that history and transforming it into a community that promotes healing and reconciliation.

“Our program is unique,” remarks Executive Director Ann-Marie Metton, “because we look for writers who have a purpose and because we are a community, rather than an institution.” The mandate of the program is to be “a centre for writers in which they can reflect on issues of conscience and reconciliation and write about their own personal experiences or the experiences of others, past or present.” Writers accepted for the three-month residency live in the house and combine their writing with community outreach projects, such as writing workshops, reading circles, and author presentations.

In addition to the writer-in-residence program, Historic Joy Kogawa House, by its own definition, stands “as a cultural and historical reminder of the expropriation of property that all Canadians of Japanese descent experienced after the bombing of Pearl Harbour in 1941.”

Stolen Property And Bad Memories

Ray Iwasaki, a member of the Kogawa House community, is working on a historical novel of his experiences both in the internment camps and on Salt Spring Island before the war. His family lost their 640-acre property on Salt Spring Island, which included approximately 3.2 km of waterfront along the south-western edge, known today as the Sunset Strip. The waterfront footage alone has been divided into 60 lots, recently valued at $1 million each.

The sale of the Iwasaki property on Salt Spring Island is documented in Ganbaru: The Murakami Family of Salt Spring Island, a self-published account by Rose Murakami, which also describes her own family’s experiences during WWII.

Ray’s family stayed at Hastings Park for a couple of weeks before they were sent to the mining town of Greenwood, in the interior of BC, where they were expected to live in a partitioned building. Their section had no windows and a bare lightbulb. Ray remembers that the walls were not very tall and that if you were in the top bunk you could see into your neighbour’s quarters.

Holding Onto Their Home

Ray’s father, Torazu, was not happy; he arranged for them to move to an abandoned house outside of town where he thought they might be able to farm. He could see that there was going to be a need for food to feed all the interned families, and he had to keep up with the tax payments on his Salt Spring Island property. The government had frozen Japanese-Canadian bank accounts and Torazu was considered too old to do the only work that was available—building roads such as the Hope-Princeton and the Yellowhead Highways. It was heavy work with pick, shovel, and wheelbarrow because the Japanese-Canadians were not allowed near the explosives.

The Murakami family was sent to work on the beet farms in Alberta, where they walked 8 km just to get to the fields. In Obasan, Joy Kogawa portrays the back-breaking work of harvesting beets in the hot sun. Many of the families who worked on the beet farms lived in chicken coops. The Murakami family was eventually moved to Slocan, BC, where tents were the only housing available for the – 40°C winter.

Meanwhile, back on the coast, the sale of Japanese-Canadian property continued. Ray’s family managed to remain in possession of their land until just before the war ended. The Iwasakis had somehow managed to pay their property taxes throughout the war. But nonetheless, Murakami’s book states, the title of ownership of their property was transferred to the Secretary of State, and then to the Salt Spring Lands Ltd. for $5,250. The president of the Salt Spring Lands Ltd., Gavin Mouat, was the appointed caretaker of the property. The Iwasakis took their case to the Supreme Court of Canada but it ruled against them in 1968. They never returned to the coast.

Reasons Behind The Japanese-Canadian Internment Camps

People have argued that the internment camps were created to protect the Japanese-Canadians from the racial tension that was building on the coast — from the accusations, the headlines, and the fear of violent outbursts. But Andrea Smith, who teaches BC History at Langara College, wonders why, if that were true, the government did not do anything to reassure the public. They had found no evidence of subversive action on the part of the Japanese‑Canadians. “They might have tried to calm the waters,” says Smith, “but you don’t see political figures doing that.”

Others suggest that the government was actually helping to create the racial tension and that MacKenzie King, the Prime Minister at the time, was using the public’s fear to further his own political agenda. Upon Canada’s entry into the war, King had promised that he would not demand military service. However, as the war progressed, pressure from the allies increased and he was forced to reconsider. If he could have made a case for homeland security—if there was a reason to protect the country from within its own borders — then it might have been easier for the country to accept mandatory service. Homeland service was preferable to sending young men overseas, so the Japanese-Canadians served his need for an enemy within. The fishermen, in particular, were some of the first to be targeted because “they knew the coastline so well. It seemed very possible that there could be spies amongst them,” says Smith.

Uncovering The Real Threat

An article from the 2004 issue of The Beaver, written by Norm and Carol Hall, looks at the circumstances surrounding the mysterious attack at Estevan Point on Vancouver Island and suggests it could have been Americans who made the attack — not the Japanese — in an attempt to build support for mandatory military service in Canada.

The National Association of Japanese Canadians reports in Democracy Betrayed: The Case for Redress that on February 24th, 1942 the cabinet, under the War Measures Act, was actually acting against the advice of several agencies concerned with national safety. The Department of National Defense, the National Defense for Naval Services, and the RCMP all felt that the Japanese-Canadians were not a threat to national security. They were a peaceful, hardworking, and successful community. Perhaps their success was the real threat.

Their success, which could be seen in the pioneering efforts of those who settled on Salt Spring Island, could also be seen in the businesses that developed along Powell St. in Vancouver. Business was one of few options available to Japanese-Canadians who were denied access to white-collar professions because they did not have the right to vote. The Japanese-Canadians were also successful fishermen. In the reports of the House of Commons, it states that the politicians of the time described the success of the fishermen as a problem because other communities were having trouble competing with them. The Japanese‑Canadians developed their communities out of necessity, because they did not always feel welcome in areas outside of Powell St. or Steveston. They brought that sense of community with them to the internment camps, where they built up thriving businesses once again.

Building A Community

When asked how he felt about his Japanese heritage after the internment, Iwasaki replied, “The interesting part of it is, we were a group. In other words, there were very few Caucasians. There was mostly Japanese and everybody was basically in the same situation and kids played…. We were basically a unit.”

Renovations to restore the house began this spring. The original windows will be reinstalled in the sunroom at the front of the house and a pair of French doors will, once again, open up into the living room, says Tamsin Baker, the Lower Mainland Regional Manager for The Land Conservancy. Other long-term hopes include digging down and raising the ceiling of the basement for a caretaker’s living space.

The Writer-in-Residence

For now, the only person living in the house is the writer chosen for the residency. “There is a very comfortable bedroom,” says Ann-Marie Metton, “and it adjoins the work space, which was Joy’s bedroom as a child.” It looks out over the backyard and the cherry tree, which is covered in knitted wool flowers from a yarn bombing event back in February 2011. The house is small but Metton says it can easily accommodate a couple, or maybe even a family.

The latest participant of the writer-in‑residence program is Deborah Willis, whose community outreach projects involved writing workshops for teens, and a workshop for children with Sarah Maitland. She also co-facilitated a writing workshop for sex workers and former sex workers in partnership with Aaron Golbeck of the Downtown Eastside Studio Society. Finally, she offered a reading program for newcomers to Canada in partnership with the Taiwanese Canadian Cultural Centre.

This last group met for their fourth week on a rainy Friday afternoon in March, in the cozy living room at Kogawa House. The smell of fresh baked banana bread wafted up from the coffee table. Each member of the group practiced their English as they drank cups of tea from handmade Japanese teacups. They commented on a story from Willis’s book, Vanishing and Other Stories, which was nominated for the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize and the Governor General’s Award. As a group they appeared happy and comfortable with each other, laughing generously at their mistakes in pronunciation and understanding, yet speaking the language well enough that they were able to tease one another and make some very funny jokes. Willis commented, in a press release, that the experience of doing community work “balances the more private work of writing. It has been a wonderful way for me to experience living in Vancouver.”

Past Residents

Other award-winning authors have resided at the house, such as Susan Crean in the fall of 2011. Her book The Laughing One: A Journey to Emily Carr, was the winner of the Hubert Prize for Non-Fiction and she was also a nominee for the Governor General’s Award. She created the Writing for Social Change Reading Series on Sunday afternoons at the house, which included visits from authors Evelyn Lau and Eric Tamm, as well as First Nations activist Shirley Bear, and First Nations playwright Tara Beaghan. There was also a workshop on writing your family history in collaboration with Larry Wong, author of Dim Sum Stories: A Chinatown Childhood.

Historic Joy Kogawa House reminds us that the Japanese-Canadian internment happened and that people’s lives were damaged by it; that they suffered physically, emotionally, and financially because of it. As long as history is remembered we can work to prevent it from happening again. But Kogawa House is more than that. While it has roots in the past, its branches are reaching into the future. By hosting First Nations artists and activists, and by helping to develop writers from marginalized groups, Kogawa House, through its community outreach programming, is giving voice to others who have suffered under government legislation. By doing so it assists in their healing. In this way it has become a thriving community that acknowledges the past while it works to transform the present.