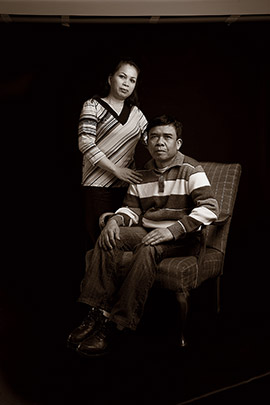

He was 22 years old when he stepped on a landmine. Now, sitting comfortably in a lounge chair in his Delta, British Columbia home, 54-year-old Sarith Keo slowly rolls up his right pant leg to reveal exactly where his leg was broken. Right at the knee is a deep cleft where the landmine struck. The explosion left him with his right leg two inches shorter than his left. Today, he is thankful.

“I’m still alive.”

Keo grew up in the Kingdom of Cambodia during a time of political unrest and turmoil, and narrowly escaped genocide.

In 1975, a Marxist group of rebels known as the Khmer Rouge seized control of the capital city, Phnom Penh, and effectively, the entire country. They enforced an extreme social reconstruction to create a clean slate—an agrarian society with no class structure. Peasants, the sick, the elderly, and children were spared from immediate execution and sent to the countryside as slaves. Anyone who had political power, religious status, education, wealth, or independent thought—deemed threatening to the new regime—was tortured, executed, or left to starve and die. The bloody purge resulted in an estimated 1.7 million deaths. After years of living in terror, young Keo was ready to leave his war-torn country behind.

Fleeing To Safety

His way out presented itself in 1979 when Cambodian rebels and Vietnamese forces allied to take control of Phnom Penh, forcing the Khmer Rouge and all under their regime to flee. A flood of refugees, including Keo, who was conscripted as part of the Khmer Rouge army, poured across the border into Thailand. He remembers long days and nights of non‑stop trudging through uncharted jungles.

“We didn’t have enough food, we didn’t have enough water,” he says. “Some people never made it.”

The Khmer Rouge littered the border with thousands of landmines as part of guerilla warfare tactics against Vietnamese troops. When Keo crossed a wire in a pathway, he triggered a nearby landmine and set off an explosion that hit his right leg.

“I just separated from the crowd of people for a few seconds and I got hit—boom,” Keo says. “Nobody could help me.” Only one person responded to Keo’s pleas for help, promising to come back with aid, but he never did.

“Two days and a night I was left in the jungle alone,” Keo remembers. To stop the bleeding, he tied a krama, a traditional Cambodian checkered scarf, to his injured leg. Local Thai villagers brought him water and some rice, but warned that they could not interfere with military tasks and help him out of his position. Armed soldiers came and left many times, but he didn’t know what it meant.

The soldiers came back after a few days with a hammock, but no explanation. They carried Keo out of the jungle and brought him to a nearby Buddhist temple. A monk visited every day and brought food, but he did not utter a word. When the monk finally spoke, weeks later, he told Keo that he was a lucky boy.

“He [the monk] said they were going to shoot me,” Keo says. “They didn’t want to treat any more refugees and it would’ve been better that they were left to die.”

He also learned that had he been taken for treatment, he would have had his leg amputated. Instead, with the use of traditional herbal remedies, his leg healed naturally and he taught himself to walk again. After three months of healing, the monk told him that he could leave when he wished. Keo set off for a refugee camp with one leg two inches shorter than the other.

He said they were going to shoot me. They didn’t want to treat any more refugees and it would’ve been better that they were left to die

At one of the refugee camps, he came across the opportunity that brought him to Canada. He learned some basic English while volunteering with American ambassadors who set up the camp. In 1983, he met Mao Eang, and married her shortly after. They had their first son in 1984.

Finding A New Life

Together they decided to make the big move to North America to give their budding family a chance at a better life. Keo’s first attempt was not successful. He found himself barred from American citizenship because of his previous affiliations with the Khmer Rouge. He applied for Canadian citizenship, telling the same story. This time, his request was accepted. Armed with little money, few English words, and a one-and-a-half-year-old son, the couple set out to start a new chapter of their lives. They arrived in

Vancouver in 1986.

“Life was different. It was safe, but it was still hard,” says Eang. “We had no friends, no relatives—it was a weird feeling.” They found they were unable to shop, to cook, even to turn on the stove, because they couldn’t speak English.

Keo and Eang enrolled in English classes at a local church where they met Bill and Gwen Burnett, who taught there. With new words and new friends, the couple’s life took a turn for the better.

“She [Eang] was quiet,” Bill Burnett says, “but one day, she spoke up and invited us for dinner.” The Burnetts enjoyed a traditional Cambodian dish cooked with eggs and meat in the sparsely furnished house that Keo and Eang were renting. Gwen Burnett remembers that it was not a nice place for a young family to live—or for anybody to live.

“It was so wet!” she says about the house. “There were pipes leaking; the bathroom was covered in water.” Over dinner, they learned how much Keo and Eang wanted to be in a better place for their son to grow up, but that it was difficult to save enough money to move.

The Burnetts felt a connection with the young family and extended an offer to help them with their situation. “Why don’t you live with us for three months? We wouldn’t charge rent.” Keo and Eang graciously accepted, and three months turned into 13 years. Soon after moving into the Burnetts’ Delta home in mid-1987, they learned that their family would be growing by one. The Burnetts knew that they must lengthen their offer if they were to truly help a young, growing family. Keo and Eang welcomed their second son in 1988.

Although they have since then moved into their own home, they still consider the Burnetts to be a part of their family.

Keo says he cherishes those who have helped him shape his life. Eang has been his partner in every turning point since they met. His sons have grown up without fear. The Burnetts helped make a new and foreign place feel familiar.

Keo reaches for his glasses case behind his chair and pulls out a yellowed black‑and‑white photograph, no bigger than a few centimeters. It’s a portrait of the man who saved his life.