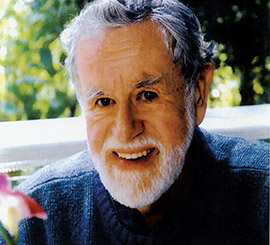

Jack Hallam is not an average senior citizen. He is an active animal rights supporter, a proponent of Dying With Dignity (an organization advocating end of life choices), and a committed philanthropist. When asked about his life, Hallam recalls events with keen detail and refreshing honesty; his voice is strong and confident. Behind bright eyes, a snow-white beard, and a devilish sense of humour, Hallam is also something else. He is gay.

Jack’s Story

Growing up in Toronto, Hallam completed an honours degree in Biology at the University of Toronto. After a year in London, England working briefly for an aquarium while teaching biology at a grammar school, Hallam returned to the University of Toronto to complete a PhD in Zoology. It was upon his return from England in the winter of 1955 that Hallam came to accept the nature of his sexuality. For the first time in his life, Hallam joined in the gay rights conversation and surrounded himself with like-minded individuals.

In the early 1970s Hallam began to attend meetings held at the university conducted by the Community Homophile Association of Toronto (CHAT). His friends organized the start of The Body Politic, Canada’s first gay publication, later replaced by Xtra! Both publications played a major role in shaping Canada’s LGBTQ community. Despite the legalization of homosexuality in Canada in 1969, Hallam was arrested in 1970 and falsely accused of “counselling to commit an indecent act” with an undercover police officer. After a preliminary hearing and a three-day trial in February of 1971, Hallam was acquitted.

The LGBTQ community in Toronto endured a decade of brutal police raids and harassment culminating in the infamous bathhouse riots on February 5, 1981. Over 250 men were arrested in gay bars and bathhouses in an attempt by the government and police to drive the establishments out of business. The campaign came to a grinding halt as the gay community and its supporters gathered in the streets in protest of police action.

Hallam now lives on Salt Spring Island in British Columbia—a liberal community and safe haven for LGBTQs who can be “out” without much fear of open homophobia. Yet at 84, despite living in an accepting community, Hallam is still resistant about going into a long-term care facility. “I would hate to go into our local nursing home because we’re always going to be a minority,” he says. “Maybe in Vancouver and Toronto acceptance has gone forward enough that people wouldn’t run into any open bigotry. There would still be some straight people who were uncomfortable though.”

The 84-year-old recently bequeathed a sum of money to Omar Khadr—a convicted war criminal at the age of 15—to help fund Khadr’s education once his prison sentence is complete. Hallam garnered some media attention and a mixed public reaction after writing a letter to Maclean’s regarding the bequest. In the letter Hallam said, “I am sure Omar Khadr would not approve of me: a gay, atheist, octogenarian, retired zoologist.” From this disclosure of his identity, Hallam received an email that stuck with him. “I got a long email from a guy in a small town in BC: 86 and he has never come out. He lives in a small community of 600 and he says he’s always looking over his shoulder wondering what they’re whispering about him,” said Hallam.

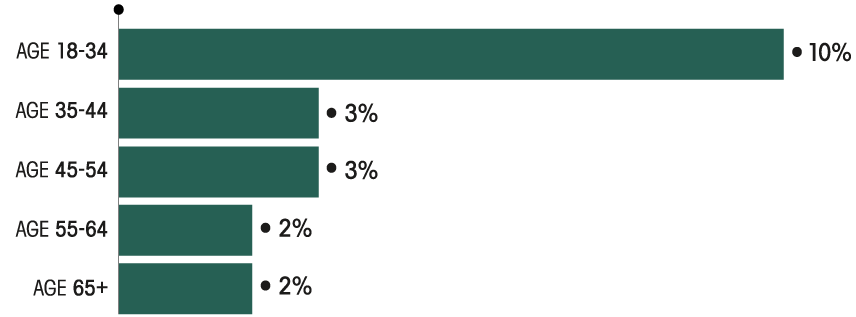

Hallam and the man from Peachland are not alone. According to the recent Statistics Canada report in September 2012, the number of people aged 65 and older surged 14 per cent over the past six years to nearly five million. Moreover, the report marked a drastic increase in the number of people identifying as being in a same-sex relationship: up 42 per cent to just under 65,000 couples. These measurements alone equate a growing demographic.

A Discussion on LGBTQ Retirement

Potential challenges associated with aging are likely a shared experience for many, but the challenges for the LGBTQ population can be magnified. The tagline of the 2011 documentary Gen Silent by filmmaker Stu Maddux may have said it best: “The generation that fought hardest to come out is going back in.” As a group, they are less likely to have children who can provide care or aid in decisions involving financial or health matters. Elderly LGBTQs may not have supportive relationships with their families at all due to their sexual identity.

The generation that fought hardest to come out is going back in. – Gen Silent (2011)

Many have come out later in life after living as heterosexuals and have families that they are now estranged from. An aging LGBTQ population may be less likely to trust the healthcare system, as homosexuality was considered to be a mental illness by the Canadian Psychiatric Association until 1982. They may also be less likely to trust police in times of crisis, as was Jack Hallam’s case in 1970. A combination of these circumstances can lead many LGBTQ elderly people back into the closet in long-term care settings. The fear and vulnerability, real or perceived, of trusting strangers with the most intimate details of life can lead many elderly to isolate themselves and hide their identity.

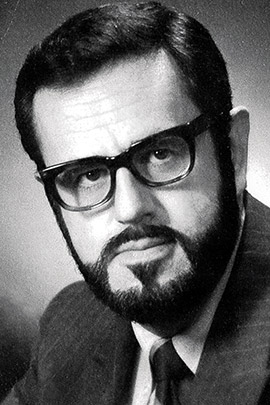

Brian O’Neill

This isolation can be more of a concern for seniors who are newcomers to Canada. While the LGBTQ community in Canada has the right to marry, many countries around the Pacific Rim do not have basic laws prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation. In some countries, homosexuality is a punishable offence by law. For those coming to Canada from these countries, the newfound freedom can be a mixed blessing. Dr. Brian O’Neill, an associate professor and Chair of Field Education at the University of British Columbia’s School of Social Work, published a study in 2010 on the challenges faced by lesbian, gay, and bisexual newcomers to Canada. “People could feel that within their own ethnic community it would be very unacceptable to be gay. Then on the other hand, when they would go to ‘mainstream’ gay places, some of them felt marginalized based on their ethnicity. So they feel isolated in the ‘big gay world’ and they feel isolated in their home communities. They lose where they came from, and then come here and still feel isolated.”

Qmunity

Dara Parker, Executive Director of Qmunity, also recognizes the added complexity of gay seniors who are newcomers to Canada. Qmunity, Vancouver’s LGBTQ resource centre, runs the Generations program, which offers community development programming and diversity training, as well as advocacy for LGBTQ older adults. “Within a marginalized group, there are people who are further marginalized—people of colour, people with disabilities. Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of ethno-cultural diversity within our users of the Generations program. One of the barriers, especially for newcomers to Canada, would be language. Even not knowing the language of LGBTQ culture would be an added challenge.”

Opinions about an LGBTQ-centered retirement community are mixed even from within the community itself. “My hesitation is around the philosophical underpinnings of integration versus cultural exclusion,” said Dara Parker of Qmunity. “I think that the projection of a queer-centered facility is a good one, but not to the exclusion of others. I think it will only work if allies are invited.”

Plum Living

The concern about isolation is echoed by Plum Living, an LGBTQ-friendly Vancouver-based business that provides home health care support. “I think isolation is the primary concern for an aging LGBTQ population. People aren’t accessing support in health care and are really alone. On our intake forms, most of our clients can’t identify someone for us to call should they become very ill or die,” says Dean Malone, CEO of Plum Living. RainbowVision Vancouver, an extension of Plum Living, has proposed the creation of a progressive-living community catering to the needs of the LGBTQ community and their friends, families, and allies. The response, however, has been smaller than expected. “People aren’t getting older,” says Malone sarcastically. “They aren’t accessing help until they’re a wreck. Getting older is always somebody else other than ‘me.’ ”

When people talk about older adults, it’s always about someone else; but I guarantee you, it is you and I, and we are going to face the same things.

Malone recognizes the importance of a place where LGBTQs can be safe and have services that are responsive to the unique needs of the community. “There are those who think it’s about sequestering us away from the rest of the world, but it’s not true,” he says. “We just happen to live in one building. It doesn’t mean we’re locked in. It doesn’t mean straight folks don’t come and spend time with us, and it doesn’t mean that our allies don’t live there with us. There are always nasty comments like ‘Well, why do they need it?’ And my response is: ‘Queer folks just haven’t done it yet.’ The Jewish community has done it and the Greek community has done it—no one questions it if golfers want to have a retirement community together. So all types of people with similar interests or perhaps similar culture come together. We’re just another community that’s thinking of getting older. As you get older, no matter what community you come from, usually you like to have things around that are familiar and that you have a shared experience with. So why wouldn’t we? Why couldn’t we? We’re just another group of people.”

Karen

Karen, a retired therapist and out-lesbian since the late 1970s, sits with her arms folded in a teak-framed chair, her legs crossed and propped up on a footstool. Her apartment is close to “the Drive”—an LGBTQ-friendly Vancouver neighborhood—and is bright and comfortable with a stunning view of downtown. Books are piled high on the coffee table, most of them about spirituality and various religions. “I think it’s a really good idea,” says Karen about a queer-centered retirement community, “at least at this time in history. I think there are a lot of people who would only be comfortable in a place like that.” She proposes, “It would also be an important stepping stone to other retirement communities becoming more open and conscious and educated on the subject. It’s heartbreaking that people feel like they have to go back in the closet at the end of their life.”

The needs of an aging LGBTQ community may be unique, but one thing is universal: we are all aging. In a society obsessed with the preservation of youth, there seems to be a general denial about growing old. Dean Malone warns, “When people talk about older adults, it’s always about someone else; but I guarantee you, it is you and I, and we are going to face the same things.”