Gaokao

In most regions of China the educational system focuses on rote memorization. This technique enforces learning through repetition and has been criticized for stifling self-expression, limiting creativity, and encouraging fact-based knowledge rather than critical thinking. One of the most publicized aspects of this system is the gaokao exam.

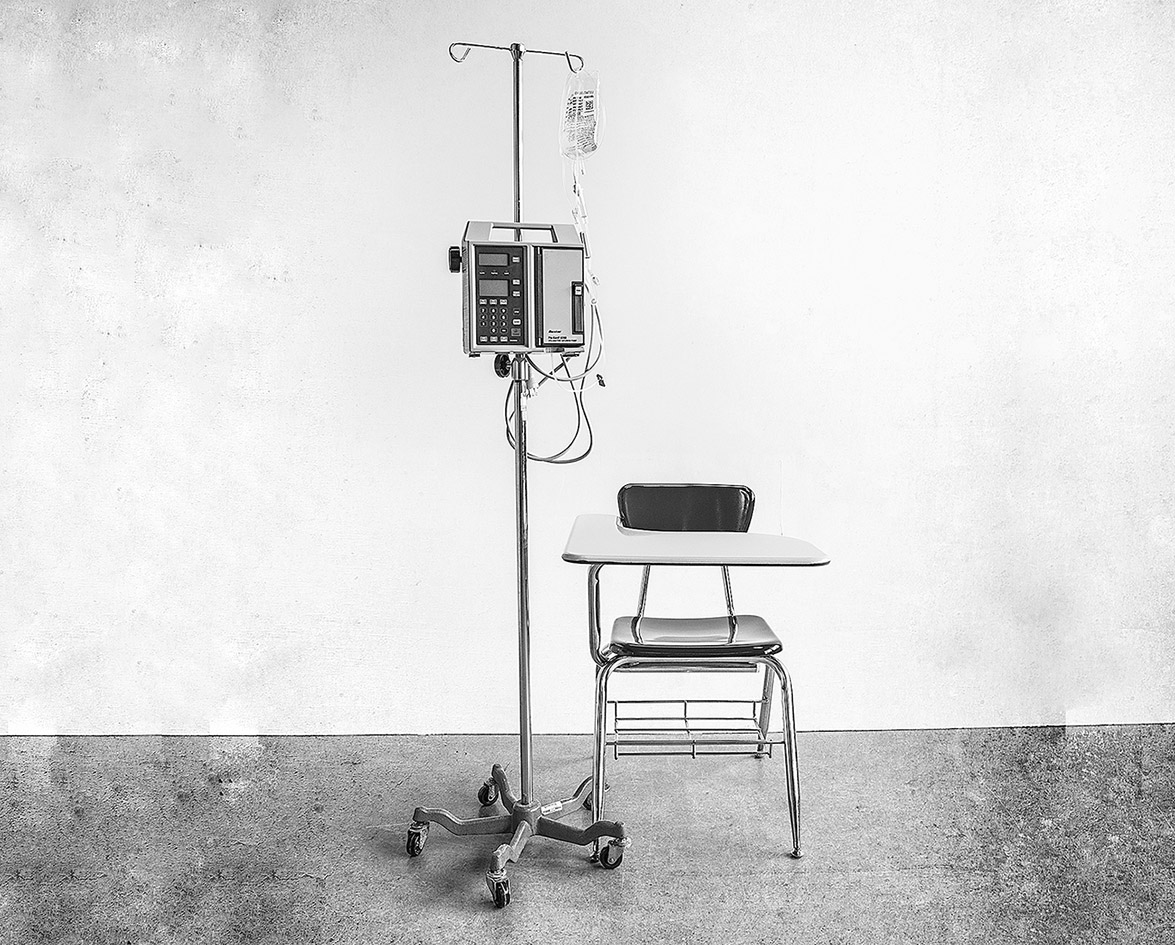

The controversial gaokao exam lasts for nine hours over a span of two or three days. It places an extreme amount of stress on students, because most Chinese universities use exam results to place students into specific programs. Students are left with little choice in their future career. In early 2012, photos were published of students in the classroom receiving amino acids through intravenous drips for energy to study for the gaokao.

This educational model has produced students who are highly intelligent, but test results are only one way of measuring the success of a country’s educational system. The number of gaokao registrants is falling because, especially in big cities, students have more choices. “A lot of students choose to go to college in North America,” says Catherine Liao, who has researched higher education reform in China. “If you look at the rural areas, their resources are lacking. They still use the rote memorization technique because gaokao is the only way for people to get into university in these areas.”

Xing Wei

Xing Wei College began offering classes in September 2012 to a classroom of 30 students, and is the first liberal arts college of its kind in Mainland China. Situated in Shanghai, the college follows a bold mandate to foster innovation and inspire creativity. The school is architecturally striking, designed in a sleek, modern style and complemented by bright colours and classrooms that receive plenty of natural light. It was built with the belief that an academic experience can be enhanced by a pleasing physical environment. Here, students are free to pursue their interests rather than have their majors chosen for them. Opinions and self-expression are encouraged through open dialogue between students and faculty. The classes are taught in English by experienced American professors like David Stafford, who says the school is “much more than just an idea; it is a dream becoming reality.”

The value of a liberal education is yet to be proven effective in China. However, Stafford is hopeful the school will be a success. He believes that over time “the cognitive skill set is something that the Chinese will find valuable” and believes people “don’t distrust liberal arts because they dislike it, they just don’t know what it is.”

The Chinese Educational Development and Cooperation Association reports that students seeking university education overseas has risen from 30 to 40 per cent between 2011 and 2012. But now with the increase of Western-modelled liberal arts programs in China, students may not have to leave the country. Hopefully Xing Wei can help prove that the skills a liberal arts education provides, such as open communication and leadership, are of great value in a global economy.