Japanese theatre remains an important part of Japanese culture. Many traditional forms are still widely practiced today, including Nō, Kabuki and Bunraku. Based in Vancouver, Yayoi Hirano, owner of Yayoi Theatre Movement Society, has been professionally performing Japanese and Western-style theatre in both Japan and Vancouver for 40 years. Since the establishment of her company in 2002, she has produced, directed and performed in a series of stylistically daring plays.

Each aspect of Hirano’s plays is meticulously planned and executed: the costumes, props and masks are all strategically thought out for each show. The elaborate costumes are made specifically for each production months in advance. Paired with the costumes are Hirano’s handmade masks.

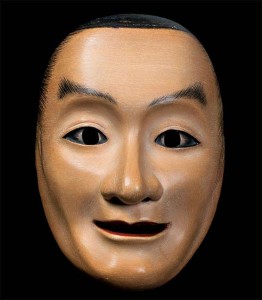

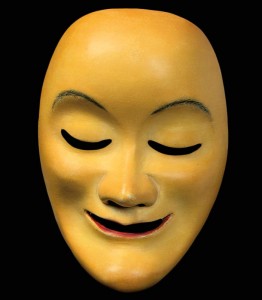

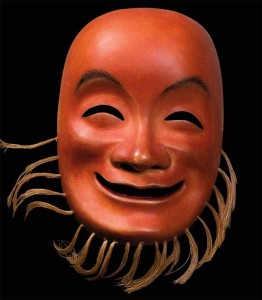

In Japan, Hirano trained with a master carver for several years to learn the craft of traditional mask carving. She loves using masks in her plays and has a collection of almost 20 that she has created. “Each mask takes at least three months if I carve every day,” she says with a laugh as she mimes carving a mask. “The design process is easy, but it’s the carving that is a bit tedious.” Using traditional materials—cypress wood, Japanese glues and paints—and techniques, Hirano handcrafts each mask. In Japan, Nō masks follow traditional guidelines. There are general categories for the masks: young, middle aged, elderly women and men, and demons and devils among other characters. However, Hirano designs new faces for her own masks. “A lot of them are in Nō style, but some of them are totally different than anything that’s ever been done before,” her husband Douglas Owen explains. “Some are traditional Nō masks, but most are her original creations,” he says.

Masks are not the only things that Hirano is putting a creative twist on. In November 2013 she and the Yayoi Theatre Movement Society put on an adaptation of the Greek tragedy, Medea. What makes performances by the Yayoi Theatre Movement Society so unique is that they combine multiple styles of traditional Japanese theatre into their performances.

Hirano manages to cohesively splice Nō, Kabuki, and Bunraku with Western-style theatrics to produce shows that are creative Japanese-Western hybrids.

With chanting instead of singing, the movements in Nō are slow and the speech is poetic yet monotonous. Nō was an official ceremonial art between the fifteenth to seventeenth century and its style has not changed much since. Kabuki, in contrast, is a fast and energetic style of dance. Originally performed by women, Kabuki quickly became very popular and many dance groups formed. However, women performers were soon banned because certain female groups used Kabuki as a front for sex work. As a result the roles started to be performed by young boys. When the same issue arose with the boys, older male performers adopted the art and this remains the tradition to this day. Bunraku is Japanese puppet theatre. The puppets, which are usually three to four feet tall, are handled by three or four masters at a time.

“A lot of [the masks] are in Nō style, but some of them are totally different than anything that’s ever been done before.”

Hirano has brought together an excited, supportive group of performers and stagehands from around Vancouver. “I started to teach Nō chanting last year, and a lot of those people were on the stage for Medea,” Hirano says. While there is no shortage of available performers in Vancouver, keeping them around to work becomes a problem. “A lot of actors in the Japanese community are moving around, so it’s really difficult for some of them to continue working with us long term,” Hirano explains.

Vancouver audiences are very receptive of the non-traditional approach Hirano takes to her work. While Hirano’s performances would be considered controversial in Japan, she does not run into that problem in Vancouver. Colleen Lanki, art director of the Vancouver-based Japanese dance company Tomoe Arts, is another artist who combines Japanese dance with Western elements.

“I did a show a number of years ago, where I was using almost 100 percent traditional choreography, but I was performing with a Nō flute—totally not something one would do!” Lanki laughs. “They were all new choreographies, but the pieces themselves—I was stealing the movements. The dance was completely traditional, but I costumed it in modern outfits. And when we took it to Japan, it was received with an almost quizzical interest, or ‘Wow I didn’t think I’d like this, but I really did.’”

In Japan, the younger community loved what Lanki was doing to the traditional dance. Older Japanese audiences are more accustomed to traditional styles of theatre and dance, so it is more of a shock to them to see people experimenting with different styles. Lanki says that there will always be some people in Japan who are more forgiving and accepting of her work because she is a foreigner performing Japanese theatre. In Vancouver, Hirano and Lanki are reinventing Japanese dance and theatre by putting their own spin on them. Whether or not the audience understands the difference is not an issue for Hirano and Lanki, as long as they can expose Vancouver audiences to the elegant traditions of Japanese dance and theatre.