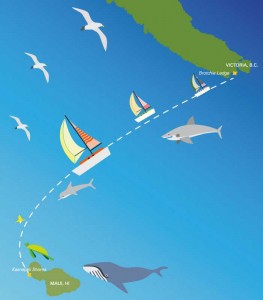

Jim Innes had been toying for some time with the idea of running a sailboat race from Victoria to Hawaii before he launched the first informal Vic–Maui Yacht Race in 1965. Only four captains competed that year—Innes himself and three skippers that he convinced to join in the adventure. The Vic–Maui Yacht Race has grown considerably since the first official competition in 1968 and now includes anywhere from 4 to 37 sailboats.

Innes passed away in 2001, but his son, also named Jim, has followed in his father’s footsteps. “I think I was nine or eight when the first race headed off in 1965,” Innes says. By the time Innes was 12, he was sailing the race with his dad and has been passionate about boating ever since. In recent years, he has volunteered behind the scenes, mentoring participants in the Vic–Maui race and competing in the 2010 and 2012 events.

David Sutcliffe, another volunteer, is the chair of the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club (RVYC) Vic–Maui Event Committee, which co-hosts the event with Maui’s Lahaina Yacht Club. A four-time participant, Sutcliffe is passionate about the race’s potential to bring people together. “The human story of working together as a team, doing the training ahead of time, getting in the race, working hard to do well in the race, struggling through challenges like gear breakage on the boat or bad weather—those kinds of things present all kinds of highs and lows for the sailors, and so there’s a real human drama to the whole thing,” he says.

The Challenges

According to Innes, “It takes more than just going racing with people. It takes getting everybody together, getting everybody on the boat, getting them trained on the boat, but it’s also just sort of building that camaraderie [that] you have to have if you’re out there on watch for somebody.” This is why, when it comes time to choose a crew, picking someone you know is not always the best strategy. Innes recalls hearing stories about otherwise healthy friendships straining under the pressure. Even someone you trust on land, he warns, may “become a different person offshore.”

“There’s nothing worse than having a sour apple in the pile,” he says. “It can go sideways pretty quickly, and then all of a sudden your entire energy is being spent on crew management rather than racing the boat.” And considering that the 4,279-kilometre race takes at least ten days to complete, conserving stamina is crucial—especially when one takes into account the number of problems that can arise during the journey.

Sailboats will occasionally become dismasted or lose their rudders when faced with heavy weather, forcing the crew to go into survival mode in order to get the boat back to a port where they can do repairs. Sutcliffe describes these emergency situations as “headline-type stuff ” that happens rarely but tends to ruin the trip for everyone involved when it does. “One minute you’re racing to Hawaii and the next minute you’re trying to figure out whether you can limp 500 miles to San Francisco with no steering,” Sutcliffe says.

The Rewards

It may sound arduous, but there are also “spectacularly good things that happen [out] there—mostly in what I would call the nature department,” Sutcliffe adds. The “nature department” is the main attraction for him and many of the Vic–Maui participants; there are sights in the middle of the Pacific Ocean that simply cannot be found anywhere else. “You could be sailing along and the next thing you hear is a loud pssshhh right beside the boat, and it’s a humpback whale who’s decided to parallel the boat for 10 or 15 minutes,” Sutcliffe says. “Or it’s a pod of one thousand dolphins, and maybe they’re spinner dolphins, so they’re leaping out of the water and spinning and doing acrobatic things.” It’s not unusual to spot sea turtles or even sharks during the journey, and albatross have been known to follow crews around for days preying on flying fish.

“When you’re out there 1,500 miles from Hawaii and 1,500 miles from land, the closest land is straight down. It’s kind of an odd thing to think about.”

When he’s not dealing with lightning storms or equipment failure, Innes amuses himself by observing the local wildlife. “There’s these silly birds out there that don’t have webbed feet. And they land in the water,” he says. “At nighttime, you hear them. The first time people hear them, they think there’s bats out there.” Despite these unsettling noises, he says that some of the trip’s more contemplative moments happen at night, when one’s perception of ordinary noises intensifies in the darkness. “You always have the sound,” he says. “You’ve got the sound of the ocean, and the waves breaking and rolling up behind you.”

On clear nights, the light from the moon and the stars illuminates the water. “The stars go right into the ocean. It’s an amazing thing to see because there’s no horizon,” he says. “When you’re out there 1,500 miles from Hawaii and 1,500 miles from land, the closest land is straight down. It’s kind of an odd thing to think about.”

The arrival

When they finally do reach Maui, crews are greeted by a welcoming committee, along with mai tais and food. “[Whether] it’s three in the morning or not, there’s people standing on the dock when that boat comes in,” says Dan O’Hanlon, the chair of the Lahaina Yacht Club Vic–Maui Event Committee. “They put flower leis on the boat. It’s a kind of welcome-back-to-land aloha greeting thing.”

Once all of the boats have arrived, or when the time limit has been reached, it is time for the banquet. After everyone has eaten their fill, the award ceremony begins. “There’s even an award for last place,” O’Hanlon says. “I don’t even think it’s really about the awards for most of them. It’s about the fact that they did it.” With all of the racers together in one place, it is the perfect opportunity to swap tales about their experiences at sea. “There are a lot of good stories from the different boats and the captains,” O’Hanlon says. “It’s a great wrap up.”

According to Innes, it is not until the end of the night that exhaustion really sets in for the racers. “When you get that first night in a bed without everything moving around, you’re pretty crashed out for a couple of days,” he says. “It takes quite a while to get yourself back up.” Most people will spend a few days recuperating in the warm Hawaiian sun before they turn their boats around and begin the trip back to Victoria. This time, however, the crews are free to use their autopilot systems and are not pressured by time constraints.

“You could be sailing along and the next thing you hear is a loud pssshhh right beside the boat, and it’s a humpback whale who’s decided to parallel the boat for 10 or 15 minutes.”

Innes enjoys the slower pace of the return journey. Once he gets about 1,200 miles north of Hawaii, he likes to stop the boat and go for a swim. “The water temperature’s like 32 degrees, but you’re in 20,000 feet of water,” he says. The water is so clear that when he looks at his boat from under the water, it is as if it is floating in the air.

While Innes deeply values these moments of clarity and calm, he also acknowledges the very real hardships that a lengthy ocean race can present. “You can say all these cute things that you want, that it’s challenge and teamwork,” he says. “It’s all these things that we hold ourselves up to, but at the end of the day, it’s a real test.”

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

Sailors travelling to Hawaii from Victoria as part of the Vic–Maui race often come across debris from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a giant collection of garbage drawn together in the North Pacific Ocean by a large circular ocean current called the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. Because much of the trash that ends up in the ocean is not biodegradable, it breaks apart into microplastics and accumulates in the centre of the gyre. The pieces are so small that it is impossible to analyze them with satellites, which makes it difficult to determine the size of the patch, although scientists have estimated that it is likely at least 700,000 square kilometres wide.

Vic–Maui competitor Jim Innes has seen the debris first hand, and says that things only seem to be getting worse. “The plastic stuff is the biggest offender,” he says. “There are a lot of countries that border the Pacific Ocean, be it the South Pacific Ocean or the North Pacific Ocean, that throw junk in the water.”

The garbage patch was first discovered by Captain Charles Moore, a scientist who was participating in the Los Angeles-to-Honolulu Transpacific Yacht Race.