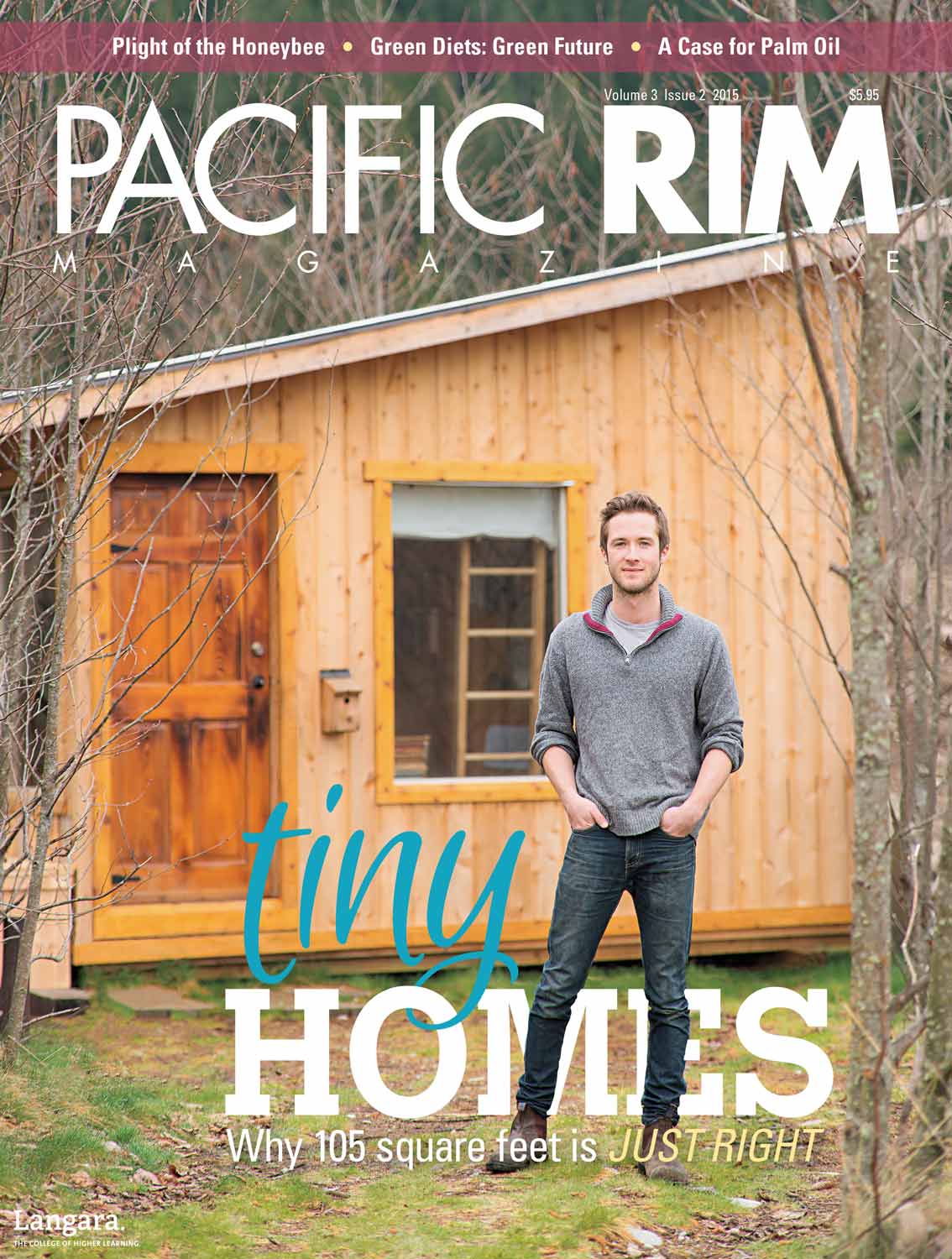

Aaron Feicht sits at the dining room table in his home in Squamish, British Columbia. The table, a rectangular slab of glossy pine, is unremarkable until you notice its distance from other areas of Feicht’s house. A step to the left, and you’re in the kitchen. A few steps up a ladder, and you’re in the bedroom. A step to the right, and you’re out the front door. Feicht’s home is tiny — a mere 105 square feet — and technically, it’s illegal.

Feicht is a part of the tiny house movement, a growing trend towards building small and living simply. Ranging from 100 to 500 square feet, tiny homes come in all shapes and sizes, and have become symbols of the bigger issues surrounding housing and lifestyle in North America. Designed and hand-built by Feicht, his house is a component of his graduate thesis project at Quest University in Squamish. He is trying to answer a big question: what is a home? It’s a question that North Americans have had to face head-on since 2008, when the Global Financial Crisis forced many into the realization that their homes, mortgages, and lifestyles were simply unsustainable.

Grey Zones

Not far from Feicht, Denham Trollip and his partner Eileen Krol are pursuing their own dreams of small-space living. Their mobile trailer sits on a slice of commercial property in downtown Squamish, with access to the waterfront and sweeping views of the Stawamus Chief. Trollip, relaxed and still tanned from a summer of teaching kiteboarding in Howe Sound, tells of how in 2013, he and Krol hatched a plan to build a tiny home. It would be an upgrade from their trailer, but would allow them to maintain their location and lifestyle. After debating for some time over whether to tackle the project, Trollip says they woke up one morning, looked at each other, and said, “Are we doing this or not?”

The answer was yes. Within a few days, Trollip sourced a used commercial trailer bed for $1000, and he and Krol started construction.

Tiny homes exist in a grey area when it comes to municipal zoning bylaws. They are often built on trailers to avoid building codes that limit the minimum square footage of a habitable structure. Building on a trailer placed Trollip and Krol’s tiny home in the realm of the RV, which meant it needed to be inspected and insured by the Insurance Corporation of British Columbia (ICBC).

Unfortunately, after three months of building and $10,000 invested in materials, Trollip and Krol’s tiny home construction came to a screeching halt when a visit from a building inspector resulted in a Do Not Occupy order. Spirits low, they decided not to pursue the project any further, and eventually sold their partially-completed home to an eager buyer who was ready to have the building properly inspected and insured.

Financial Crisis

For Trollip and Krol, the biggest motivation behind their decision to live small is financial. Even with the failure of their tiny home project, they prefer small-scale living. The $200 a month they pay in rent for their mobile trailer allows them to work as much or as little as they want: “We’re not deadbeats; we’re not hippies. We’re just regular, mildly intelligent people who enjoy life and doing lots of different things,” says Trollip. “We pay our taxes and we contribute to the community, but we just have more of our hard-earned money available to us to do what we want.”

Krol chimes in, adding that living debt-free is a priority. “We don’t pay installments for our lifestyle,” she says. “We own our lifestyle. The tiny house was a project to see how luxuriously we could live while still living within our means.”

The average Canadian doesn’t share Trollip and Krol’s mentality. According to a November 2014 article by Pete Evans of the CBC, the Canadian Real Estate Association (CREA) reported that the average price of a Canadian home reached an all-time high of $420,000 in October 2014. Although reasonable by Greater Vancouver standards, where the average price of a home sits above $800,000, these prices can still result in huge mortgages, debt, and massive spending.

Space and Functionality

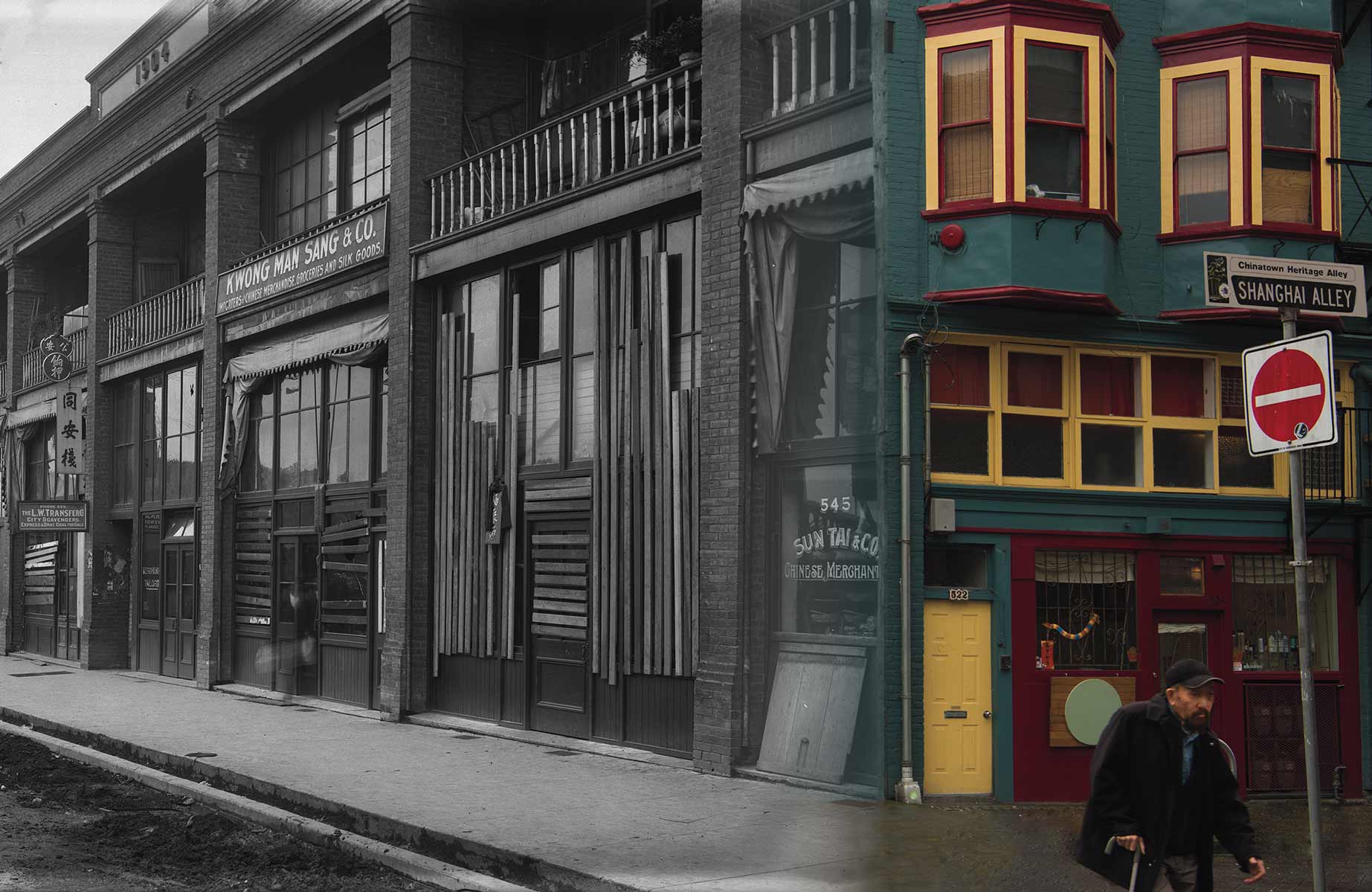

Across the Pacific Ocean, Japanese architects have been at the forefront of small-space design for years. In a story reminiscent of the housing crisis that hit North America, Japan’s bubble economy popped in 1989, leading to an increase in small-scale building practices. In her book Small Houses: Contemporary Japanese Dwellings, Claudia Hildner writes that building small in Japan has flourished due to a lack of design guidelines and a general openness to unconventional architectural ideas.

In population-dense urban centres like Tokyo, there is an increasing demand for tiny residential lots, which can be as small as two metres wide. Relaxed building codes allow Japanese architects to create striking, highly functional homes within these compact spaces. Author Azby Brown writes in his book, The Very Small Home: Japanese Ideas for Living Well in Limited Space, that all successful small houses in Japan have one thing in common: good lighting. A mix of man-made and natural light is essential, and there should always be a connection to the outside world.

The idea of transparency between the interior and exterior of homes is a design concept that Vancouver designer Bryn Davidson also adheres to in his small-scale creations. As owner of the firm Lanefab Design/Build, Davidson has been at the forefront of the laneway housing boom in Vancouver.

Davidson’s foray into the world of small-scale housing started in 2008, when he and his wife bought a 360 square foot condominium as an experiment. They wanted to know how small they could live, and what they could do with the space to make it livable. Not long after, the Global Financial Crisis hit, and in an instant Davidson lost a year’s worth of architecture projects. With this loss came an unexpected opportunity to turn his personal interest into business, and in 2010, Lanefab became the first in the city to build a legal laneway house.

Multiple uses, or what Davidson calls “layers of use,” are key to Lanefab’s clever small-space designs. Placing a sink just outside the bathroom door means that one person can use the toilet while another washes his or her hands. Galley-style kitchens create a flexible space where you can eat, read, watch TV, or cook. Storage is also key: “A big part of [small space design] is having a place to put everything away. So when you are sitting in the space, it’s very clean and minimal,” says Davidson. Laneway homes may be on the larger side of “tiny” (the minimum size is 280 square feet according to City of Vancouver bylaws), but creative designs like Davidson’s are a progressive step towards more sustainable housing.

Lessons Learned

Back in Feicht’s kitchen, light filters softly through the large window, illuminating everything but the cozy loft sleeping space. Feicht explains that for him, building small stemmed from an environmental consciousness. Two large 250-watt solar panels sit outside the house collecting energy for basic 110-volt power. Small appliances, including a fridge, stove, and heater are propane-fed; thick, well-insulated walls keep heating costs to a minimum. With no sink, Feicht washes dishes outside using water he collects in a barrel. His house is completely off the grid.

As in the case of Trollip and Krol, Feicht got a visit from a district building inspector mid-construction. At 105 square feet, his home is considered an accessory structure, but legally, it breaks building codes. Because Feicht chose to build his home on the ground and not on a trailer, his house is deemed too small to live in by the municipality.

“Don’t you think it’s a little silly that people are starting to build houses for themselves that they can afford, that are sustainable for the environment, that people are proud of, and that we limit these things?” Feicht asks.

Feicht was lucky enough to receive special consideration for his building as a student on Quest University property, and can continue to live in it, but his experience (along with Trollip and Krol’s) raises some poignant questions for those whose tiny home dreams are killed by municipal bylaws.

A look of contemplation crosses Feicht’s face as he reflects on some of the lessons he’s learned on his tiny home journey. He stresses that only having as many possessions as you actually need and use is key when living small. Feicht’s shopping habits have also changed; garbage storage and disposal is a challenge with limited space, so he opts for products with less packaging and waste. He says that, for the most part, people are intrigued by his tiny home and simply want to know how it’s working out. For others, it’s confusing — why would anyone want to live in a space that small?

Feicht, however, is able to look at the bigger picture. He sees his home as a catalyst for sparking new ideas and conversations about the way we live. One hundred and five square feet might seem like a small space for such big questions, but with a little ingenuity, the tiny house movement might just be able to provide some answers.