Meet Kramer, a Vancouver, BC, teenager of Indonesian heritage. He is chatty and clever, but has not always shown it. His personal journey has been tumultuous; he has had several different homes in his short life, including a stint in a fraternity house (which is evident in a few of his choice phrases). Though he was difficult and sometimes violent when he arrived at his most recent home, his new caregivers were patient and kind. They eventually gained his trust, and he began to reveal his charm and intelligence.

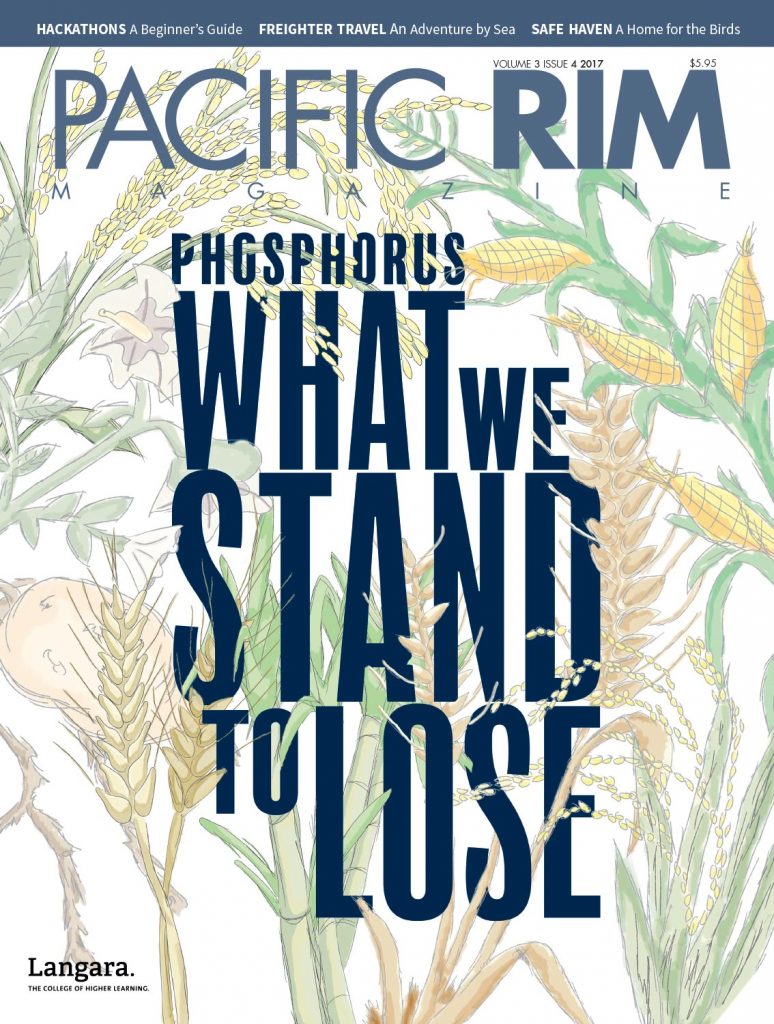

Kramer is a salmon-crested Moluccan cockatoo. He is now safe and happily living in the Bloedel Conservatory, a city-funded sanctuary for exotic birds. The glass-domed conservatory, located in Vancouver’s Queen Elizabeth Park, houses over 200 birds of a variety of species including African grey parrots, Amazon parrots, cockatoos, macaws, and finches. Vicky Earle, one of the founders of the non-profit association Friends of the Bloedel, says most of the birds at Bloedel were adopted from aviaries, sanctuaries, and individuals giving up their pets.

Kramer’s story is not uncommon. The need for sanctuaries like Bloedel is, in large part, the result of ignorance regarding the care of exotic birds. Many species of birds are highly intelligent and demanding of their owners’ time and attention. Earle likens these birds’ behaviour and intelligence to that of a human toddler. Moreover, larger species like macaws have been reported to live up to 100 years in captivity, which means birds can outlive their owners. Even smaller species like budgies can live up to 20 years: a longer time commitment than a cat or a dog. “It’s common for parrots to get re-homed five to seven times in their lifetime, and most parrots bond for life,” says Earle. Separation can cause a great deal of emotional distress for birds.

Greyhaven Exotic Bird Sanctuary (Greyhaven) is a volunteer-run organization based in Surrey, BC. Jan Robson, education coordinator at Greyhaven, is keen to spread awareness about the realities of bird ownership. The sanctuary took in 584 birds from the World Parrot Refuge in Coombs, BC, after it closed in the summer of 2016. Approximately 230 birds remain in Greyhaven’s care.

Birds can also end up in sanctuaries after their original owners have died and left the bird to a friend or family member who may not have the same ability or inclination to provide the level of care and attention the bird needs. Robson says the best home for an exotic bird is a knowledgeable one. Prospective owners have to be aware that birds can only be domesticated to a point; the birds remain largely wild animals. They are noisy and messy, and these behaviours are usually impossible to train away.

Despite these difficulties, the demand for exotic birds remains high. Bill and Shelagh Stienstra ran Tamarac Aviaries in Kelowna, BC, for close to 25 years until they sold it in 2013. Tamarac Aviaries sold birds to large pet stores, and Shelagh says the demand was constant. “We were never in a position where we couldn’t sell the birds.” African greys were the most popular due to their high level of intelligence. “We actually had quite a few that were just special. You have to be around them to really understand it.” Shelagh recalls an African grey owner she knew who struggled with depression. “Her African grey always pulled her out of it. The bird just seemed to sense when it was time for lots of snuggles or a little chatter.” The level of care required for a bird can force a person to get up in the morning, or go out to buy food, or just sit with their bird and connect. “There are a lot of people who say we shouldn’t be breeding,” says Shelagh. “This is the flip side to it.”

Greyhaven has a pet therapy program where they bring birds to nursing homes to visit with residents. Robson recounts the end of a session when she and the other volunteers were asked to visit the dementia patients. Ivy, a little green mitred conure, was perched on Robson’s wrist. To the surprise of the staff, Ivy’s noise caused one of the dementia patients to smile. “They had never seen her smile,” says Robson. “Ivy did her job that day.”

It seems unlikely that education alone will eradicate the demand for companion birds. People love them too much. The bonds birds can form with humans often go both ways. Earle says that many of the people who give up their birds to Bloedel do not want to, but life circumstances such as a move or a change in health means that some owners are no longer able to provide the best life for their bird.

Greyhaven’s sponsorship program allows bird lovers to help, even though they may not be in a position to adopt a bird themselves. However, Robson says the program has more value in spreading awareness than generating funding. Sponsors tend to be educated about birds, and they may encourage a friend or neighbour interested in getting a bird to consider their decision carefully. That decision could protect a bird like Kramer from the trauma of being shuffled through a long series of homes.

Birds of Bloedel

Gidget

Species: Citron-crested cockatoo

(Cacatua sulphurea citrinocristata)

Origins: Lesser Sunda island and Indonesia

Mali

Species: Greater sulphur-crested cockatoo

(Cacatua galerita galerita)

Origins: Eastern Australia

Carmen and Maria

Species: Green-winged macaws

(Ara chloroptera)

Origins: Northern South America

Rudy

Species: Congo African grey parrot

(Osittacus erithacus erithacus)

Origins: Western and Central Africa