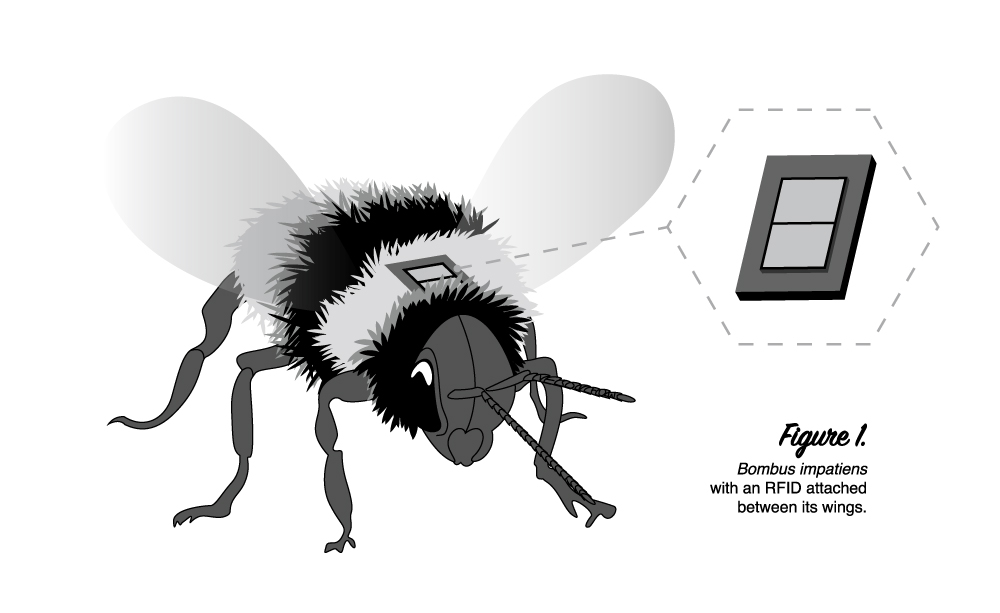

A radio-frequency identification (RFID) chip rests between the wings, where there is just enough room for the device to sit. Roughly 600 Bombus impatiens, otherwise known as bumblebees, have this device glued to their backs. It is an arduous task, says Levente Orbán, PhD, psychology professor at Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU), BC. Tagging a colony of 600 bumblebees takes time, patience, and a great deal of dexterity. But, once a bee is tagged, Dr. Orbán can examine where the bee travels and, more specifically, where the bee lands and spends its time.

Dr. Orbán says 10 years ago, bumblebees were considered an odd subject for a psychological study. When he began graduate studies at the University of Ottawa in 2008, Dr. Orbán expected to study pigeons, which were considered a suitable study subject in the field of comparative psychology. But when he arrived in Ottawa, ON, his doctoral advisor encouraged him to study bees instead. Dr. Orbán says it turns out bees are much easier to work with, as they are cleaner and smarter than pigeons. With the support of his supervisor, he began studying the Bombus impatiens.

Dr. Orbán is interested in cognition and his research primarily asks questions about learning and memory. Bees make good study subjects for his research because, quite simply, bees have brains. And while Dr. Orbán is quick to point out that we cannot draw conclusions about human cognition based on his findings, we can learn more about the nature of cognition itself.

In studying bumblebees, Dr. Orbán asks fundamental questions about cognition. In his most recent study, “Visual Choice Behaviour by Bumblebees (Bombus impatiens) Confirms Unsupervised Neural Network’s Prediction (2015),” Dr. Orbán examines the decision-making behaviour of bumblebees, looking at why bees choose certain patterns — like the sort of pattern they would see on a flower — over others.

The bumblebees in his study were presented with patterns that were simple, complex, simple and symmetrical, and complex and symmetrical. The bees preferred simple patterns to complex ones. When bees were presented with complex patterns and complex symmetrical patterns, they chose the complex symmetrical pattern. Dr. Orbán says this is because a symmetrical pattern is easier for the bee to interpret as it “only has to encode half that pattern, then it duplicates the rest.”

Studying cognitive processes is valuable in and of itself, which is precisely why bees, who are small, smart, and easy to work with, have become one of psychology’s study subjects. But, bee populations are in decline. Kent Mullinix, PhD, director of Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems at KPU, says, “As an agriculturalist, the decline of bees is something I concern myself with because without bees we don’t feed people. The ecological systems of earth will grind to a halt.” There is no singular reason bee populations are in decline, but their decline illuminates their utility. Without bees, we would not have any agricultural systems and we would not be able to feed ourselves, never mind study cognition.

Given current conditions, Dr. Orbán is amazed that bees are not dying faster. “We know why the bees are dying,” he says. “It’s not so much a surprise that they are. Businesses want to maximize profits. There is no political will to create regulatory framework that ensures agriculture is arranged in such a way that it is bee friendly.”

Dr. Orbán continues to research bees. He is currently overseeing a study examining why bees land on flowers that are already occupied. Is another bee signalling them? Or is the landing bee trying to take the other bee’s food? Perhaps both? Bees are helping Dr. Orbán, and other comparative psychologists, ask fundamental questions about memory, learning, and cognition.

Comparative psychology is able to make use of bees, not because bees are different, but rather because comparative psychology acknowledges the commonalities between bees and humans. Bees and humans have evolved intricate networks of neurons. And while a human brain is much more complex than a bee’s, they are both tasked with making sense of the same world.