Tessa Reed remembers molding clay with plastic bags over their shoes in the backyard shed of James Black Gallery. The shed was uninsulated and its patchy roof did little to protect Reed from the city’s relentless rain. This was the choice: wear several coats and plastic layers, or forget about ceramics. Since then Reed has moved the studio into the basement of James Black Gallery, away from the elements. It’s an improvement, but in Vancouver’s real estate market, it is likely only a short-term option.

As studio prices continue to climb, development consultant Michael Ferreira is calling high rents the “new normal,” as reported by the Vancouver Courier in an October 2017 article. Higher rents pose a problem for artists and those who want to live in an art-filled city.

“Space is an issue that’s constantly being discussed,” says artist and curator Jennifer Dickieson. “So many spaces go because the rent is too expensive. There’s high burnout too, because everyone is working seven jobs—it’s a very Vancouver thing.”

Vancouver artists aren’t the only ones struggling. Rent for studio and gallery space in art-centric cities like San Francisco is increasing. It’s no longer Jack Kerouac’s “Frisco,” in which a generation of painters and poets had the luxury of affordable spaces. Instead of lounging about on fire escapes, many artists gather after their second job in order to share eviction stories. These stories are of experiences shared from San Francisco to Vancouver, and across the Pacific Rim to other expensive cities like Tokyo.

Creative Solutions

Leave it to artists to come up with creative solutions to near-impossible rents. For example, in July 2017, Karen Hansen organized a series of art events called Sky Island. The shows required no walls at all as she used the rooftop of a Chinatown building as a showroom. “People talked about Sky Island all year. We were all climbing ladders up there. It was magical,” says Dickieson.

Sky Island was created as a direct response to the unaffordability of space, and even though it was beautiful and whimsical, the gallery was not viable during Vancouver’s wet months.

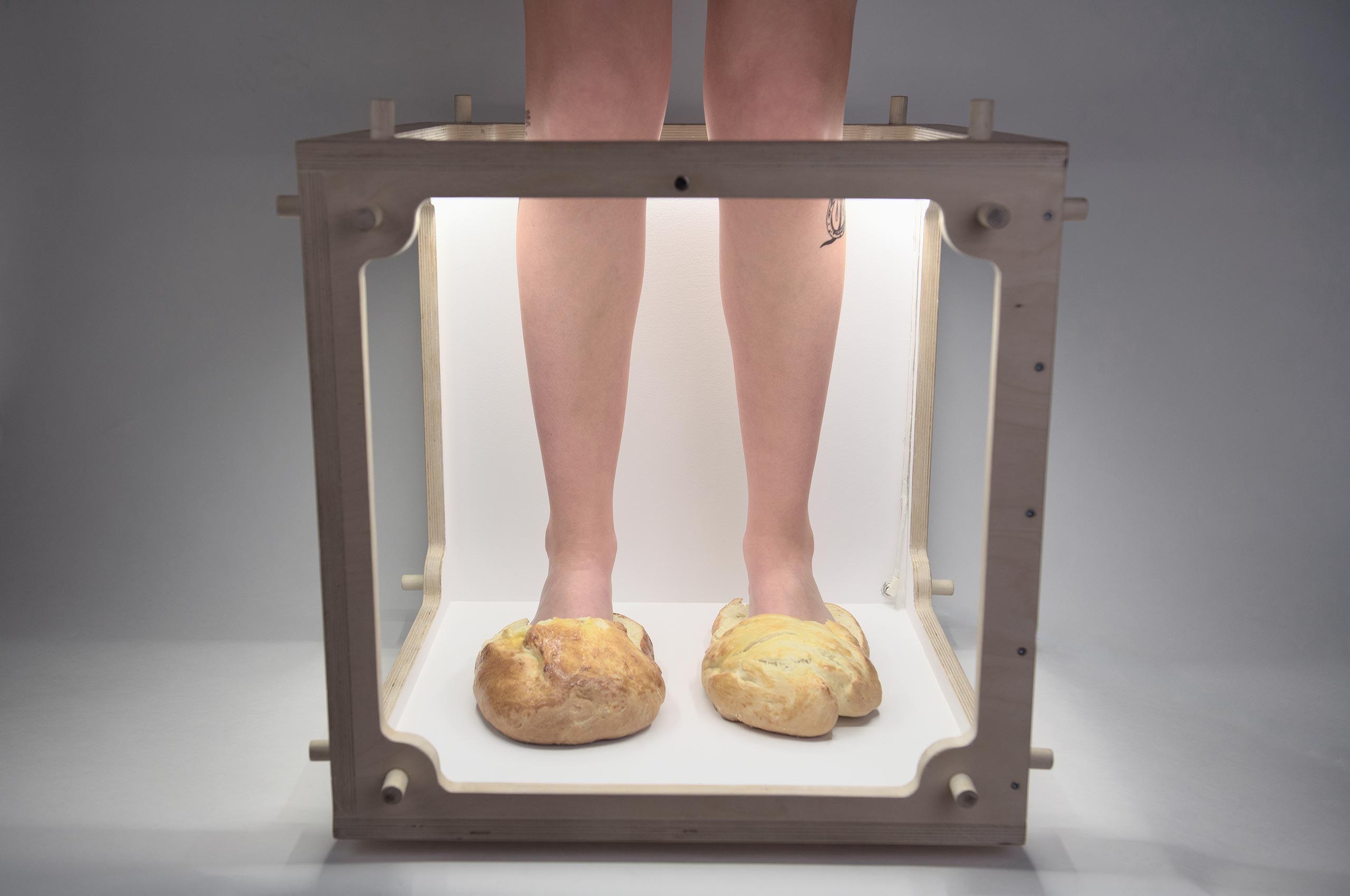

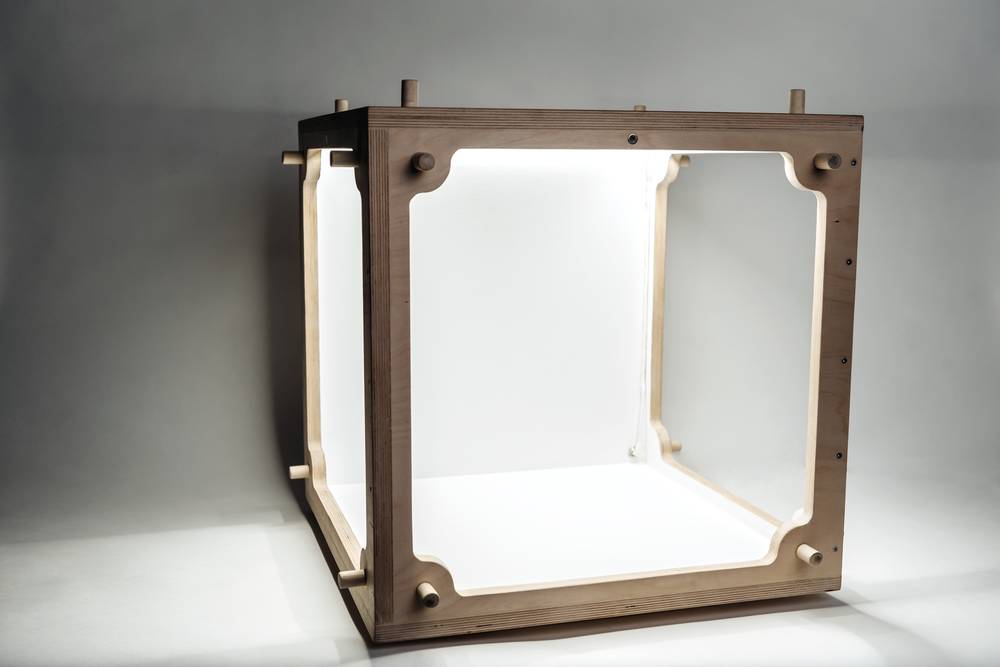

Standing at nearly 50 centimetres tall is Number 3 Gallery, another innovative approach to housing constraints, designed and built by Emily Carr graduates Julie Mills, Julia Lamare, Pongsakorn Yananissorn, and Logan Mohr. Number 3 is a mobile “micro-gallery”—essentially a square box with windows and a wooden frame. The micro-gallery travels between different locations in Vancouver. All graduates have a hand in its design and coordination. Number 3 Gallery is a tongue-in-cheek meta-piece of work itself, one that forces you to consider the conditions artists are working with in the city.

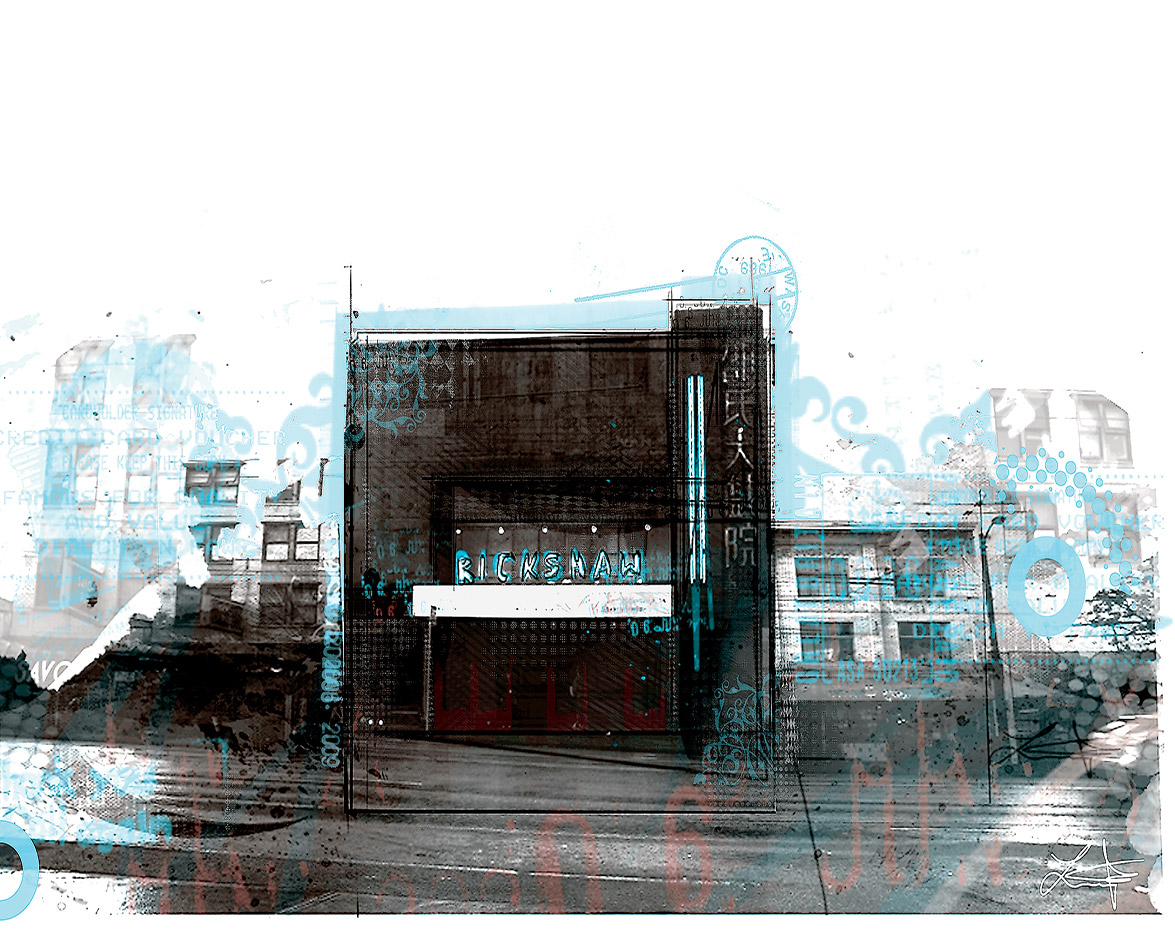

Instead of thinking small, Tokyo artist collective BCTION went big. As artists in another expensive city, they recognize the importance of space—even if it’s just temporary. The collection took over an abandoned office building, which is now the site of a multi-floor art gallery. A video on their website bction.com presents a shot of each floor from the outside. As the camera pans down, it reveals a lavender room filled with yellow balls on one floor, black and white murals on another, and rooms with dim lighting and musicians on the other floors. The once bland interior bursts with life.

These wall-less, tiny, and temporary solutions are delightful and innovative, but they are not sustainable or flexible.

Leading the Way

San Francisco’s rising rents forced many artists to move farther out to Oakland and surrounding areas, but the community has claimed a new zone to keep emerging artists in the city. The new arts district is DoReMi, which combines the names of the different districts Dogpatch, Potrero Hill, and Mission.

Three large warehouses anchor DoReMi’s arts community, thanks to the philanthropic efforts of art collectors Deborah and Andy Rappaport. Since opening in 2016, the building houses galleries, a restaurant, shopping, and arts classes. The profits all go back into the warehouse centre.

The Rappaports recognized the need for rent-controlled spaces where artists don’t have to scramble to make ends meet, and they recognized that they were in a position to do something about it. Their vision for the new space is one with a sustainable economic model that will continue to serve the arts for future generations.

Meanwhile Back in Vancouver

“Everyone is taking off,” says Megan Jenkins, a board member for Access Gallery and curator for SAD Magazine’s Disposable Camera Show. Because of this, she says it’s more important than ever to foster a community where people feel like they can stay here.

Perhaps enough artist-pioneered action and public support for rent-controlled spaces could help galleries and studios safely take root. A sustainable model like San Francisco’s DoReMi district could put Vancouver on the map as a city to visit for arts and culture, not just mountains and ocean.